In September 2011 ,the most advanced computer game to use a consumer brain computer interface (BCI) will go on sale. Its name is Focus Pocus (see video trailer here, its awesome) and it is aimed at children with ADHD so that they might use gamification to train their brains to improve focus and impulse control.

The game is based on neurofeedback enabled by the use of the Neurosky dry-electrode EEG (Electro-EncephaloGram) headset, which anyone can purchase for under $100 (or 100 Euros if in Europe) Earlier this week, BBC2 did a special on the headset. The basic Idea is that the single electrode on the Neurosky headset (placed on the forehead) is able to pick up a few simple and characteristic brainwaves (created by activity in populations of neurons), some that have been shown to be enriched when the subject is awake and attentive (ex. Beta-waves), and some when the subject is relaxed (ex. alpha waves). Neurosky has developed algorithms to funnel these and other brain waves into measures of “focus” and “meditation.” Look here for more details on how it works.

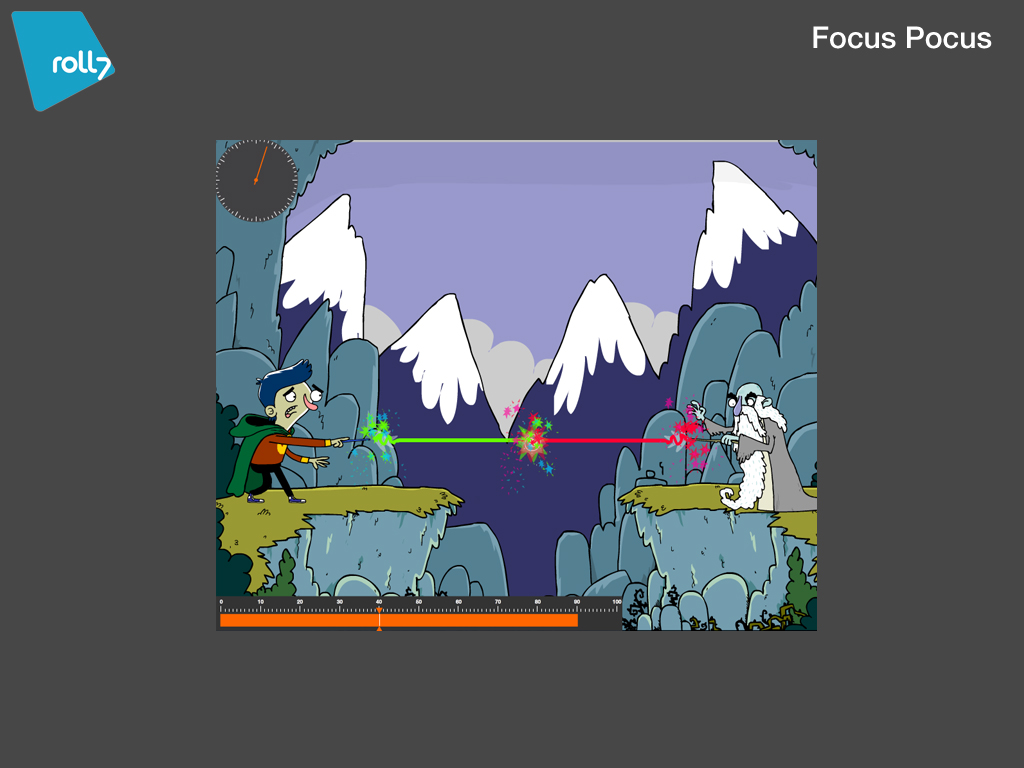

In the game, the player needs to attain a certain level of focus or meditation to zap monsters, to change one object to another in transformation class, to levitate, to ride a broomstick, or to win a duel with an evil necromancer (a bit reminiscent of Harry Potter). The idea is that through these different activities, the players would be exercising mental capacities that would generalize outside the game (into the classroom, for example). Developed by Roll7 in partnership with Neurocog and the University of Wollengong, Focus Pocus will be marketed as an alternative to medication or as an adjunct therapy for children with ADHD. The game will be available also to the general population for fun and focus-enhancement.

I, for one, can’t wait for this game to come out.

Curiosity peaked, I purchased a couple of these Neurosky Mindwave headsets last week and brought them to a class of students (as we were studying the basic principles of BCIs) to see what it was like to play videogames controlled with brain-waves. With the computer hooked up to a projector, students came one-by-one to play a few of the simpler, free games that come with the headset; the class laughed and applauded successes and gave each other tips on how to reach the highest levels of “focus”. Among strategies used were, 1. Stare at a small detain in the computer screen, 2. Recite poetry or sing a song in your head, 3. Imagine your way home from school in great detail. It seemed that the focus was affected by things other than focus on the game itself. Once, to great laughter, a student put on the headset and had no signal at all! “Oh no, I have no brain!” she said. But then we realized the electrode did not have good contact with her head and her focus levels went up. We also used the headsets to monitor attention levels as we watched a few student-made short films. At the end of the day, the class unanimously declared the technology “really really fun.”

Myndplay, a software developer for the neurosky platform, has made an archery game in which you get highest scores when your brain-waves resemble those of Olympic archers when they get bulls-eyes (see bbc2 video above for a demonstration). And another company has developed the Brain Athlete visorto help amateur golfers get into the brain state associated with good shots. Neurosky even hold the Guinness world record for the heaviest machine moved by a BCI.

Ok, you might be saying, this technology is really cool (and it is), but where is the ethical issue? This is a practical ethics blog, after all.

One ethical issue is grounded in the reverse inference problem (the idea that a certain behavior might be associated with an enrichment of particular brainwaves but an enrichment of those particular brainwaves might not be causally linked with that behavior). Gamers may train their brain-waves to look like Olympic Archers, for example, but get no better (or get worse) at actual archery. Kids may train their brain-waves to high levels of the game’s focus, but only get better at daydreaming (as might be suggested by the observation that practicing singing songs etc spikes the focus reading). Now, the reverse inference problem is not a problem at all if we are just playing video-games or playing with toys. The problem becomes a problem when we are playing the games in order to do something else, like improve our archery skills, golf game, meditation skills, performance in the classroom, or are using the information to determine which parts of films to keep or cut. These reverse inferences (which are claims about efficacy) require specific testing, preferably in randomized, double-blind, placebo and sham-training controlled trials. The consequences of unsubstantiated claims might be less in some cases (amount to false advertising in some consumer cases) than others (therapeutic misconception and/or harm due to missed opportunity or complication with other treatment in the medical application cases).

Admirably, neurocog, one of the partners developing Focus Pocus has a declared commitment to research:

“Our mission is to design and produce software solutions for training cognitive processes and brain electrical activity, and to conduct research in this area.”

And the games used in Focus Pocus are based on software that made significant improvements in kids with ADHD in a published pilot study (see a newspaper account here). But this study had a small sample size (as it was a pilot) and needs to be corroborated by further research. Though the use of neurofeedback for treatment of ADHD has other support like in the literature, its safety and efficacy is still hotly debated (see http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10874208.2010.523340, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21561933, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19207632 ).

Other products have not even been even this diligent. Mattel’s Mindflex, for example, links players floating a ball to high levels of theta-waves, which it calls “focus”. There is good evidence, however, that kids with ADHD already have theta levels that are much higher than controls and many hypothesize this enrichment to be mechanistically related to the disorder (reviewed here), which raises the question of whether playing MindFlex could actually exacerbate ADHD symptoms ? Fortunately, those at neurocog are familiar with this research on theta waves and ADHD as some of it was done by their academic collaborators. Not to mention that training specifically to increase theta waves has been reportedly associated with increased risk of seizure, resurgence of traumatic memories, and even depression (though it is worth noting that other toys, such as bicycles and pogo sticks also have risks).

A further complication is based on specificity (the idea that modulating certain brainwaves might also modulate off-target brain activity). There is some evidence that at least one of the wave-forms (theta) that games might help minimize may be helpful for other activities, such as musical performance.

Efficacy and safety concerns are typically subject to some sort of regulatory body. EEG biofeedback devices are regulated in the USA by the FDA (food and drug administration) as class II medical devices and approved to be marketed for intended use only for relaxation and muscle reeducation. Moreover, they can count as non-prescription class II devices only if their intended use is relaxation, otherwise they are considered prescription devices (i.e. not given to the general population; see http://www.aapb.org/edu_labeling_approval.html).

So should BCI games be regulated by the FDA? Though it is not clear-cut, it seems that if their intended use if for the treatment of a medical condition, they should; and that if the intended use is not relaxation (i.e. if it is rather the treatment of ADHD or delay of Alzheimer’s), then safety and efficacy data should be presented to the FDA. It is worth noting that it is currently illegal to claim efficacy in treating an illness without providing such information see http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm080198.htm) (similar to the way nutritional supplements must make a disclaimer “This statement has not been evaluated by the FDA. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.” ). Use for enhancement hazier; while one could argue that efficacy should be shown it seems like certain safety standards at least should be met.

Neurosky indicates on its website that it is primarily a tech company and that:

Our current offerings are not FDA certified as it would add time and cost to an equation that does not tolerate either well. We do not, ourselves, design medical equipment, it is not our goal. Having said that we do work with numerous developers that are, in fact, developing for the medical community. These projects range from treatment for ADHD to diagnostic/treatment systems for cognitive disorders. To support our partners in the medical community we furnish components manufactured to the ISO 13485 spec. This allows our partner to design their medical solution in a way that it is ready for them to bring it through the FDA and other medical certifications.”

It is certainly true that FDA certification and monitoring add time, cost, and may stifle innovation. But isn’t it true that these games still use the same biofeedback technology that the FDA considers worthy of the class II medical device label? Efficacy might no-longer be an issue, but safety should. But should regulation of the BCI toys and games is better addressed by consumer safety (or perhaps like video games) than by the FDA?

As the realms of medical and consumer technology blur and as the uses of such BCIs mushroom (Neurosky encourages open innovation by offering free development software to help anyone with the time and skill to develop new games for the system) these questions merit further consideration.

Hi Matt,

Not a reply, but a question : do you know of any studies linking BCI to recovery after a stroke ?

Hi Antony,

just to mention a few articles about stroke recovery:

Researchers develop new technologies for people with cerebral palsy, stroke etc.

<a href="http://neurogadget.com/2011/07/22/five-years-of-funding-18-5-million-to-brain-machine-connection-research/2429" title="http://neurogadget.com/2011/07/22/five-years-of-funding-18-5-million-to-brain-machine-connection-research/2429">

About BrainGate (the patient had a brainstem stroke and now she participate in trials with the BrainGate system, which records useful signals)

<a href="http://neurogadget.com/2011/03/25/braingate-is-still-working-1-000-days-after-implantation/1549" title="http://neurogadget.com/2011/03/25/braingate-is-still-working-1-000-days-after-implantation/1549">

Neural plasticity could strengthen connections and allow some of the brain’s functions to be rescued when impaired. This happens naturally when people recover the ability to move or speak again after a stroke or brain injury:

<a href="http://neurogadget.com/2011/02/08/implantable-bci-research-funded-by-1-million/856" title="http://neurogadget.com/2011/02/08/implantable-bci-research-funded-by-1-million/856">

Sorry, I should have specified that I was asking about recovery of cognitive functions (when motor functions are virtually all restored or unimpaired)

You mean this one:

Implantable BCI Research Funded by $1 million

http://neurogadget.com/2011/02/08/implantable-bci-research-funded-by-1-million/856

Thank you for your question, Anthony, and for your reply and links, neurogadget.

Anthony, to respond to your question: to my knowledge almost all of the current work on BCIs for stroke rehabilitation has focused on motor function. The strategies have been designed either to give patients control over a machine (to type, move a prosthetic limb, wheelchair etc) or in what is sometimes called "rehabilitative BCI" to use the brain's plasticity processes (ability to rewire to a limited extent) to regain function through some sore of neurofeedback (see http://doursat.free.fr/docs/HSS512F_F09/Daly_Wolpaw_2008_BCI.pdf for a review). A strategy similar to the latter could also theoretically be used to help regain non-motor functions (especially with more powerful techniques like real-time fMRI neurofeedback), but I have not come across any research specifically testing this possibility.

The closet we have come is highlighted by neurogadget's last link: that of an implantable neuroprosthetic chip. I will add to this link a study published very recently that showed the successful restoration of memory function in rats by implanting a chip that mimics the characteristic neuro architecture of the hippocampus (see here for press http://www.alzheimersreadingroom.com/2011/06/can-memory-be-restored-can-damaged.html and here for the abstract to the original scientific paper http://iopscience.iop.org/1741-2552/8/4/046017)

It is important to point out that invasive BCI's (like braingate and the hippocampal chip) require brain surgery and are therefore very unlikely ever to be used in the consumer market (imagine "honey, I got you brain surgery for your birthday!") in the same way we are seeing with the EEG BCIs. People recovering from stroke may be attracted to give the EEG option a go on their own to try to recover non-motor movements even though the research is not there, which creates a good example of the blurring we are seeing between medical and consumer use.

Thanks for your reply Matt : I was wondering whether the EEG route or variations/adaptation of Focus Pocus could be used to complement speech therapy….

Dear Anthony,

There is certainly a need for evidence-based treatments of speech dysfunctions after stroke. As it is, rigorous empirical support for efficacy of any of the current treatments is not substantial l (see doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60325-5, especially the ref to the 2005 Cochrane review about treatments for aphasias).

The short response to your question is no, Focus Pocus is one of a kind at the moment (and is not even out until next month). But this does not mean that variations will not be developed; I consider it highly likely that such games will be developed.

As for other, more lab-based attempts to use something like neurofeedback for speech improvement, I did a quick search and was able to come up with only 2 case studies suggesting improvements in patients with stroke (DOI: 10.1080/10874201003772155, DOI: 10.1007/BF01474514); as case-study is the weakest form of evidence, the need for larger, controlled trials should be clear before we can say anything. There was nothing I found that combined speech therapy with neurofeedback. Nonetheless, such a strategy might be promising and meriting of further research as simple EEG measures can be used to differentiate between fluent and dysfluent speech (10.1080/10874200802126118) and neurofeedback (in the form of a game or otherwise) might be used to help develop the desired signals (though this needs to be tested, as it is subject to the reverse inference problem and was conducted in non-stroke patients). Moreover, biofeedback used to cause negative shifts in slow cortical potentials in the left-hemisphere language areas of healthy subjects increased speed in lexical decisions (doi:10.1016/S0301-0511(00)00046-6)

As I mentioned above, however, caution might be warranted in such approaches as the same article showed that modulating these slow cortical potentials in the positive direction actually slowed lexical response. Just like exercising with weights in the gym, if one does not do so properly, one might cause more harm than good (and we need further research to find the proper way for neurofeedback in many cases). Other risks are present in neurofeedback systems, causing the author of this 2008 paper to encourage that neurofeedback be performed only by properly trained and certified practitioners because “Unlicensed and unqualified practitioners pose a risk to the public and to the integrity and future of the profession” (DOI:10.1080/10874200802219947). I wonder how that same author feels about consumer BCIs?

Another approach being tinkered with for speech deficits after stroke is a BCI that couples directly to a synthetic speech synthesizing device ( doi:10.1016/j.specom.2010.01.001)

There is a need for further empirical support for the safety and efficacy of even the leading neurofeedback techniques (for treatment of ADHD, for example). But we seem to find ourselves in the interesting position where the availability of games and devices might come first. Again, similar in some ways to the nutritional supplement industry.

To find a document using a DOI

1. Copy the DOI of the document you want to open.

The correct format for citing a DOI is as follows: doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2003.10.071

2. Open the following DOI site in your browser:

http://dx.doi.org

3. Enter the entire DOI citation in the text box provided, and then click Go.

Great article btw!

Full of salient points. Don't stop believing or wtrinig!

Thank you very much, Matt, for your searches and your reply.

As you may have guessed, my question was not entirely disinterested…. guess we'll just have do do the best we can and save the €100 for something more worthwhile.

Very interesting post and interesting questions.

Regarding FDA approval, or more broadly the question of regulation, my first instinct is to consider analogous cases.

You mention that we can do damage to ourselves using a bicycle, but then such damage is more likely to be from using the bicycle wrongly or in the wrong places, not from the correct/recommended use of the toy/machine as you suggest is the danger in this case.

How about the danger of self-medication by someone who is not qualified or informed to consider the potential side-effects? Is this analogous to individuals taking ritalin (whether or not prescribed for them), taking alcohol, or both? If we damage ourselves in the short term, the likelihood is that we would notice. If it is long-term, then perhaps the expectation would be that once links between long-term use and long-term damage are scientifically proven, then there can be claims for damages and safeguards can be developed. But societies tend to treat these issues incoherently:

1. Mobile phones have become widespread, and the dangers of long term damage from prolonged use are not known, but we assume the chances are small, perhaps derived from our models of human physiology and animal experimentation (I do not know). But a similar kind of testing of these headets and games might be sufficient to satisfy society. However what about internet use in general altering developing brains (as Susan Greenfield suggests based on her models)? How concerned should we be about not knowing?

2. Cigarettes were found to be damaging to health and many years of corporate sponsored obfuscation eventually failed to hide this in the face of ever more refined studies. This did not lead them to be banned, but to be regulated by primarily by warnings, forms of censorship and restrictions on sales to minors. Similarly alcohol. So social acceptability has been a key lever for regulating use and maintaining their use. Rather than compensating sufferers, the consequences are deemed to be a matter of autonomous informed choice.

3. Drugs considered illicit are regulated very differently and a great deal of energy is expended to avoid them becoming socially acceptable and to reduce their availability. The key levers also include criminal laws.

4. Prescribed drugs which have unintended side-effects are treated very differently again. If testing has been insufficient prior to release, then there is potential for great scandal. Thalidomide comes to mind. So a great deal of testing is required before being legalised for use.

So which models (if any) are relevant to these games? The post suggests to me that model 4 is most relevant, and I wonder whether this would mean this is the appropriate model also for how we ought to treat mobile phones, the internet, cigarettes, alcohol, cannabis and crack? And by using such a model (treating all the above like prescribed drugs) what would the consequences be for society? And then do philosophers need to consider whether their chosen principle is generalisable in this way before endorsing it?

I think in an ideal world, these things would be thoroughly tested before being available, but volunteers allowed to use them if they clearly waive their rights for compensation against side-effects, and ideally should be insured in some way to compensate society if any of the side-effects are anti-social or socially costly – however that then raises issues of economic inequality translating into other inequalities. If tests showed the headsets/drugs/etc to have significant side effects, then the regulations should alter to make them available only on prescription in some way. If tests showed no significant side effects then they could be made freely available.

In the real world I think we may be used to moving so quickly with technology, that it may not be possible to regulate such new gadgets until we have clear experience of a generation being damaged by unforeseen consequences of use.

Cognitive status is a function of distributive patterns in the brain. In adults they are tied mostly to phase and coherence changes in anatomical sources that match the cognitive function that is impaired or needs improvement. These devices work on increasing amplitudes which has a weak relationship to phase. IQ can improve with neurofeedback, see e.g. Tansey, M article in Journal of Australian Psychology circa early 1990s, and recently Thatcher, R. Intelligence and Phase REset in Neuroimage 2008 and Thatcher, R. et. al. Intelligence and EEG Current Density Using LORETA in Human Brain Mapping 2007. Intelligence is based on increased efficiency in local (6 cm) phase and coherence connections in the brain and long connections (e.g. 20 cm). These devices in training amplitude only may accidentally help some, but they run the risk of harming others, especially those with underlying or undiagnosed medical conditions. Increasing beta for example in a person with undiagnosed eEG kindling will run the risk of provoking a seizure which is a high amplitude high frequency event.

Gerald Gluck, PH.D. LMFT BCN SF

Comments are closed.