One argument against human enhancement is that it is cheating. Cheating others and oneself. One may be cheating oneself for various reasons; because one took the easy path instead of actually acquiring a certain capacity, because once one enhances one is no longer oneself, because enhancements are superficial among others. I would like to try to develop further the intuition that “it is not the same person any more”. I will concentrate in forms of enhancement that involve less effort, are considered easier, or faster than conventional means because the cheating argument seems directed at them. In fact, most forms of non-conventional technological enhancements being proposed seem to be easier routes towards self-improvement. I will also explore how my considerations might mean trouble for any type of disruptive technology besides radical human enhancement, such as superintelligence or whole-brain emulation.

One of the intuitions behind the cheating argument is that there is something intrinsically bad with enhancement when compared to conventional, old-fashioned hard work. Two individuals might achieve the exact same results, but if one of them works to become better and the other takes a pill, the latter created less value in the world in virtue of having taken the pill. I am convinced one common way to defend this intuition does not hold water.

It’s not the hardness of the hard working route that is doing the work. If it were the hardness, as Tom Douglas argues, then one could always increase the value of something by making it harder to achieve for no reason. It might be that becoming better by hard work has more value than by easy work, perhaps because there are more profound improvements or because there is learning in the hardships. But in these scenarios hard work pays off, you in fact became a better person because of it, the result is different. However, if by choosing the hard path one learns the exact same things, becomes exactly as good a person, produces the exact same results, violates/fulfils the exact same rules and cultivates the same virtues than by choosing an equally available easy path, then choosing the hard path does not seem to add any value. Still, we might want to say that if in World 1 Barbara takes the hard path and there is no easy path, she has higher moral worth – or higher moral praiseworthiness – than Barbara in World 2 who took an available easier path. Notwithstanding, had both paths been available on World 1, gratuitously choosing the hard path does not seem to increase moral worthiness. Overcoming hardships may mean you are virtuous, yet doing unnecessary work for no reason means you are a fool.

For something to ground the intuition that enhancement is intrinsically worse than old-fashioned self-improvement, it would have to point to some aspect of the enhancement process that is worse in itself, not because it produces worse results. As Kelly Sorensen observes, one promising area to find such aspect is that of cross-temporal dependency of moral value. If value is cross-temporal dependent, the moral value at a certain time (T2) could be affected by a previous time (T1), independently of any causal role T1 has on T2. The same event X at T2 could have more or less moral value depending on whether Z or Y happened at T1. For instance, this could be the case on matters of survival. If we kill someone and replace her with a slightly more valuable person some would argue there was a loss rather than a gain of moral value; whereas if a new person with moral value equal to the difference of the previous two is created where there was none, most would consider an absolute gain. You live now in T1. If suddenly in T2 you were replaced by an alien individual with the same amount of moral value as you would otherwise have in T2, then T2 may not have the exact same amount of value as it would otherwise have, simply by virtue of the fact that in T1 you were alive and the alien’s previous time slice was not. 365 different individuals with a one day life do not seem to amount to the same value of a single individual living through 365 days.

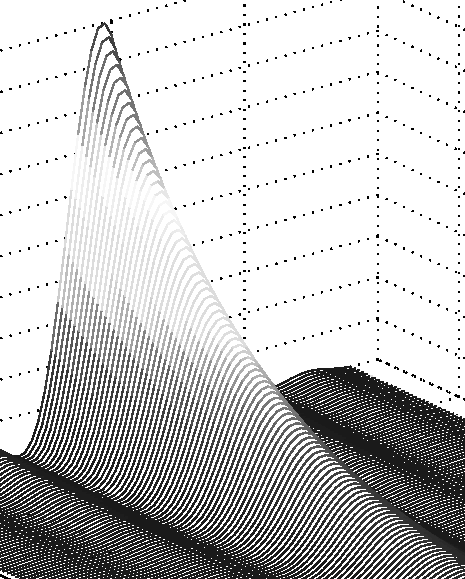

Small, gradual and continual improvements are better than abrupt and big ones. For example, a person that forms an intention and a careful detailed plan to become better, and then effortfully self-wrought to be better would create more value than a person that simply happens to take a pill and instantly becomes a better person – even if they become that exact same person. This is not because effort is intrinsically valuable, but because of psychological continuity. There are more intentions, deliberations and desires connecting the two time-slices of the person who changed through effort than there are connecting the two time-slices of the person who changed by taking a pill. Even though both persons become equally morally valuable in isolated terms, they do so via different paths that differently affect their final value.

All these examples have to do with psychological continuity. I believe this specific class of cross-temporal effects related to psychological continuity constitutes what is intrinsically wrong with certain forms of human enhancement. Effortless self-improvement through technological modification is generally disruptive. The trajectory of a racist that through reflection, life experiences, and moral deliberation gradually starts to equally care about people from different races and nationalities contains a richness of stages each one intimately connected to the next. Taking a certain combination of neurochemicals to achieve the same result might contain only a handful of stages; the racist is suddenly replaced with his non-racist version. Insofar as survival in the form of psychological continuity matters, many authors consider that abrupt decreases in the degree of psychological interconnectedness – e.g. severe stroke, teletransportation malfunction – are a greater loss than a gradual change over a wide range of time – e.g.: an long and eventful life. The first is closer to sudden death; the second to longevity. Nearly instant human enhancement is closer to death and further from longevity than gradual and effortful self-improvement is. There is a loss in what matters entailed by the nature of the dramatic change of such enhancements. Hence, they are intrinsically worse.

Finally, this disruptive loss seems to be a feature of other potentially highly transformative technologies. For instance, one central problem in creating a greater than human artificial intelligence is that there is a good possibility it will continue to increase in intelligence and power and we will not be able to control it. If its goals are not aligned with human values then it might bring about human extinction. Nonetheless, even if its goals are aligned and it brings about dramatic powerful improvements, because these improvements would happen abruptly from a human perspective there might be a loss of continuity. The same would hold for whole-brain emulations capable of fast recursive self-improvement. Just as a gradual path leading someone from racism to a more inclusivist morality is preferable to instant moral biochemical enhancement, so gradual conventional progress should be preferred to unprecedented technological change. Perhaps there would be more value in achieving the same improvements gradually, through less powerful technologies. The ability to deliver fast and dramatic improvements, one of the anticipated major advantages of such transformative technologies, could actually be an intrinsically bad feature.