Written by: Alberto Giubilini; Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, &

Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities, University of Oxford

It’s that time of the year again, when Christmas decorations start to appear way too early in shopping malls. It’s beginning to look a bit too much like Christmas. Except that, being it 2020, of course this year “it will be different”.

Pubs are very optimistically accepting bookings for Christmas dinners, but many Christmas markets are (un)fortunately being cancelled. You might still see your distant relatives on Christmas day, but (un)fortunately no more than 6 of them at any one time.

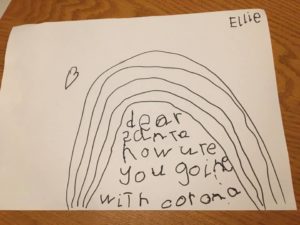

Amidst the inevitable confusion, one obvious question is whether Santa Claus should deliver presents this year.

There are various factors to consider when deciding what Santa – but indeed everyone else – should be allowed to do over Christmas. The most relevant are probably the following:

- COVID-19 infection rate over Christmas.

- Risks and benefits for others of Santa’s job.

- Risks and benefits for Santa

Infection rate over Christmas. We don’t know what the infection rate of COVID-19 will be around Christmas in different parts of the world. The strategy of many Governments, including the UK one, has so far been a flexible one. They relax measures as the number of positive cases fall or doesn’t increase too quickly, and reintroduce strict measures, including lockdowns, as the number of cases raises beyond a certain rate. The UK is adopting a localized approach that tries to tackle local spikes through local restrictions, so as to minimize the impact of restrictive measures at the national level. Lockdowns have entailed large economic and health costs (e.g. because of diseases that have been neglected, like cancer, and the impact on mental health), with very unclear overall health benefits (e.g. many countries with no lockdown or milder measures had a lower mortality rate than countries with strict lockdown), as this document details. Given this, the strategy is now that of imposing the costs of restrictive measures on the smallest number of people possible.

Whatever one thinks of these policies, it is very clear that this approach does not help Santa Claus. Like most other businesses, he needs to plan well ahead. Wrapping up presents, decorating the sleigh, getting the reindeers ready, estimating the cost of the elves’ labour: these are all activities that require advance planning. With the prospect of lockdowns looming large, the risk of investing resources now in planning business activities for Christmas might not be worth taking. And in any case, many cannot afford it. We don’t know much about his financial situation, but one thing we know for sure is that Santa Claus doesn’t like uncertainty around his business. The problem with this level of uncertainty is amplified by the fact that Santa’s business requires a functioning economic and production system to be sustained. Santa might well be available to wrap up presents, but if lockdowns (local, national, or international) prevent his suppliers from producing presents and wrapping paper, there is only so much he can do by himself.

Besides, Santa, like many others, needs to be able to travel from one country to the other and to have some reassurance now that he and his suppliers will be able to do that in the next months and on Christmas Eve. Again, inconsistencies in pandemic measures within and across countries make certain activities very difficult to plan and often not worth investing resources in.

We should not be surprised if he autonomously decided to give up this year, and perhaps furlough his elves, as more than 1 million employers have already done in the UK with around 10 million workers since March. Santa Claus is a generous chap, but is not a charity.

Benefits and risks for society. Even during the strictest lockdown, some essential workers were allowed, and indeed often expected or required, to carry out their duties, even if that entailed some risk for themselves and for others. Healthcare workers, garbage collectors, supermarket workers are a few examples. Santa Claus might well belong to this category. The risk of these people catching or transmitting the virus on the workplace was considered worth taking, not necessarily because it was low (often it was not), but because of the important societal goods that they could guarantee.

In the case of Santa Claus, we would need to decide what risks we are prepared to take and to pose on them in order to protect Christmas – the spirit of Christmas, the economy of Christmas, and Christmas dinner with those distant relatives.

Santa Claus is one of the main drivers of most countries’ economies. We should ask whether, just like healthcare workers or garbage collectors, he should be allowed to do his job during this pandemic. Importantly, a positive answer would not imply that he or other essential workers should be simply expected or required to do their job, if the risk for themselves is very high. But we could consider incentivising such additional risk-taking with adequate payments for additional risks in case of essential jobs.

In any case, it does not seem that Santa Claus would pose a significant public health threat, given that he is always so socially distanced from everyone that no one has ever seen him. Thus, considering the large societal benefits of his job and the low public health risk, it seems he should be allowed to deliver presents after all.

Risks for Santa. Santa Claus is an old overweight man, and most likely has type 2 diabetes. Each of these factors put him in a high-risk group. Men are about twice as likely to die of COVID-19 as women. People with certain pre-existing conditions (including diabetes and obesity) are at a much higher risk of dying from COVID-19. And age is the most relevant factor in COVID-19 mortality, with the mortality of those aged 80 or over estimated to be around 8%. We don’t know how old Santa is, but he already seemed extremely old when I was a child, so we can safely assume he is in the age group with the highest risk. All seems to suggest that he has a strong interest in not being exposed to the virus.

Temporarily shielding Santa?

So what should Santa Claus do this year? Should he postpone present delivery until 2021, the promised land?

Now, it seems the main problem is caused by the current approach of many Governments, including the UK one, that keep lockdown on the table as a realistic option for the Christmas season. This generates too much uncertainty. Thus, one solution could be to drop now the idea of a possible lockdown over Christmas and to let life go on (almost) as normal, without any restrictive measure. This is more or less what the signatories of the Great Barrington Declaration advocate, though for some reason they do not refer to Santa Claus explicitly.

This more balanced approach requires to prioritize alternative measures, such as temporary selective shielding (i.e. locking down the elderly and the vulnerable for a certain period of time), which have so far have been ruled out in the UK with dismissive comments appealing to some alleged form of unfair discrimination. Shielding would not necessarily require one to live isolated, of course. Santa, like anyone else, could form a support bubble with his elves. At the same time, people at lower risk could go on with their activities, thus making sure the economic and production system, including the wrapping paper industry, keeps functioning as much as possible.

True, there is some worry about the long-term effects of COVID-19 on the ‘non-vulnerable’, including some cases of organ damage. But these are more frequent in old, hospitalized patients, most of whom, like Santa Claus, would qualify for shielding anyway. Among those with mild COVID-19, significant symptoms seem to persist for more than 4 weeks in 1 out of 10 people. But it is very likely that mild and severe COVID-19 infections represent only a fraction of all COVID-19 cases, with many cases being asymptomatic. The percentage of asymptomatic cases is however very difficult to establish. According to a recent study, for instance, the range of estimated asymptomatic infections is 18% – 81% of all infections.

If we had immunity passports, things would be much easier: while Santa Claus is shielding, those who have acquired immunity could keep the production of Christmas goods going, so as to guarantee adequate supply for Santa and his elves.

Shielding could be encouraged, incentivised, or made mandatory, depending on how high the risk is for vulnerable individuals like Santa, and how burdened the public health system is. In all these cases, shielding someone like Santa Claus, at least until his essential services are needed, would be ethically justified not only because of the collective benefit of reducing the burden of COVID-19 patients on healthcare systems, but also because it is in his best interest to be protected from COVID-19, given his risk factors. Shielding people like Santa is both in the public interest and in their own personal interest.

Importantly, the relevant aspect here is not relative risk (i.e. whether the risk for certain groups is higher than for others), but absolute risk (i.e. whether the risk for certain groups is taken to be high enough). A lot of focus during this pandemic has been on how certain groups have been affected more severely than others. But that aspect is not relevant to a justification of measures like shielding: whether someone would benefit from shielding does not depend on whether the risk for them is greater than for others, but on whether the risk for them is above a certain threshold – as is certainly the case for old diabetic Santa Claus.

However, the high risk justifies shielding him until Christmas, but does not justify preventing him from doing his job on Christmas Eve. As said above, his job on Christmas Eve does not require any social interaction whatsoever. It actually is so safe that the point made above about additional payments for additional risks does not even apply to him. But of course, it would still be nice to leave him a few extra biscuits this year.

Vaccinating Santa?

There is a tiny chance we will have a vaccine before Christmas. We will of course not have doses available for many people. Would Santa qualify for priority access? That depends on the criteria we think should guide prioritization.

If we think essential workers should be prioritized, then maybe Santa should. If the criterion is vulnerability to COVID-19, then, again, probably Santa should be prioritized.

Arguably, COVID-19 vaccination policies should aim at maximizing the public health benefit of the vaccine. This would plausibly require prioritizing the interests of the most vulnerable, as they are the ones who would benefit the most from protection and therefore who are more likely to alleviate the burden of COVID-19 on healthcare systems. This might well be one of those fortunate cases where utilitarians and prioritarians could agree on the right course of action.

However, if we think we should distribute the vaccine in a way that prioritizes the interests of the most vulnerable and maximises expected utility, then Santa might not qualify for priority access. Depending on features of the vaccine we currently do not know, the most vulnerable might be better protected by targeting those on whom the vaccine is more likely to be effective, so as to increase the chances of achieving herd immunity more quickly. This would still be a way of prioritizing the interests of the most vulnerable, but one that would work via indirect protection (a similar argument can be made with regard to the flu vaccine).

Realistically, though, while availability is very limited, there would probably be very limited scope for building up high levels of immunity at the collective level, let alone herd immunity (unless there already is a high level of immunity due to infections, which is uncertain). While availability is very limited, we might still need to protect the vulnerable through direct immunization after all.

In that case, Santa Claus would qualify for priority access because his service is essential and he is at a significantly high risk. By all means, please give Santa the vaccine as soon as it is available.

Conclusion

Santa Claus should be shielded from now until Christmas, because he is in a high-risk group. Shielding Santa is justified because it is in his best interest and does not come with significant costs to him. On Christmas Eve, he should be allowed to deliver presents, given that his service is of the utmost importance for society, the economy, and children, and that the risks of his job are almost non-existent. He might be required to leave the presents outside the door and step back, as if he had just placed a bomb or an Amazon parcel.

Santa Claus would benefit enormously from a global coordinated plan about pandemic measures. This would minimize inconsistencies in policies across countries, in spite of the inevitable inconsistencies in the spread of the virus, thus reducing the level of uncertainty that makes planning for Christmas activities a very difficult job. However, such coordinated effort seems very unlikely.

If we genuinely care about Santa Claus, lockdowns at least for the Christmas period should be ruled out. After all, 2020 has already been different in too many respects.

Interesting as it applies to Santa.

My concern is that no one (that I have heard of) has directly addressed the possibility that no vaccine will be found that is effective. In that case, our Covid strategy must change. It currently is (apparently) to delay massive infection rates until protection is available. If no vaccine can be developed, or if resulting protection is marginal, our strategy must change to managing society‘s transition to “living with Covid”, accepting the continuous risk without overwhelming our health care system in the short term. Perhaps this is the insane clown president’s strategy??

In any case, this alternate circumstance would definitely favour a normal route for Santa Clause.

Thanks Brett.

Yes you’re right, much of the current discussion (including in this blogpost) is based on the assumption that we will have a vaccine relatively soon.

If we are not going to get a vaccine (which is not very likely, but it certainly is a possibility), or if it turns out we would need to wait a very long time (years) for it, the case for lockdowns would, in my view, be even weaker, given that they are not sustainable for too long. Which of course would facilitate Santa’s job, without posing much risk to him, for the reasons explained.

Yes

The Christmas toys I am going to like are a iphone and a reply rad farting car and air pods and a prank a electric one and a blanket and can you rap it and put it in the back of in the front so I can not see not

ryder,

Consider what to give others as you would like to recieve. In this, my buisiest time of the year, i am sad and concerned as well because of Corona Virus, but in many years past viruses have plauged our nation in the past, we all pulled together back then just as we do not. Check google search in past or past viruses.

I’m 11 and is Santa still going to deliver presents in a virus

I do think so. I would not be worried about it 🙂

Comments are closed.