Written by MSt student Mahdi Ghuloom

Reports this year from May indicate that the college council of Trinity College Cambridge, has voted to divest from all arms companies (Mulla, 2024). Pressure has been rising from students on universities to conduct similar actions, often in a non-discriminatory set of demands. Some of course, have been focusing on the Gaza war recently, and have limited their calls for divestment only in so far as the arms companies are “complicit” in the war. However, this is beyond the discussion: I want to focus in this post on those calling for all arms companies to be divested from, regardless of the wars they contribute to or the regimes they supply arms with.

There are two reasons behind calling for such divestments that I wish to focus on: 1) preference for personal monies to be directed towards other causes; and 2) a belief that all engagements that include the deployment of weapons are unjustified. One could describe the first with an example: a person has paid tuition fees for a university course, and does not wish that money to be redirected towards financing arms companies. The second point is one that could be described as being close to, or a wholly pacifistic approach. This is not to say that those who are opposed to universities investing in arms companies are necessarily committed to pacifism in all circumstances. However, they might believe that profit from the development and sales of arms is inherently problematic and a consequence of that materializing into policy is a pacifistic world.

As I try to make the case against full divestment, I argue that there are instances in which violence through arms is justified, therefore taking a stance against the reasoning for arms divestments which stem from pacifism. However, I will not take a stance against the first reasoning: I believe that, where possible, people should be able to direct their money towards causes that are of preference. In fact, this point in particular, is another one in support of sustaining transparent private investment in arms companies. If all private investment into arms companies came to a halt, there would still be a supply of investment from state revenues. Thereby making it harder to redirect one’s own money towards causes one supports, as state revenues stemming from taxes and fees are pooled together for politicians to decide on their distribution. They are also a legal responsibility which in most cases are unavoidable.

As for private investment, one could ultimately choose which organisations they wish to finance through academic tuition or other means. If your university is found to be, or is transparent about, investments in arms companies, then you are ultimately free to choose a competing university that does not have the same practices. This could be extended to any commercial transaction with private entities. As much as its regrettable to profit from tools of violence being manufactured and sold, a big consequence of a world where private investment in arms companies dries up, is that governments will ultimately need to rely more on taxation to sustain the industry. Some may still view that as preferable, as perhaps governments can be swayed in their policies through electoral pressures.

Now, going back to the pacifistic approach: I say this with difficulty, as I do wish a pacifistic world were a reality, but I believe that so long as humans have aggressors amongst them, then just wars and justifiable levels of violence can be achieved and are necessary. On this point, I refer to Just War Theory.

Just War theorists do indeed believe that war ought to be prevented, but not in all cases, as they believe more importantly that disasters ought to be avoided (Neu, 2011). The following are Jus ad Bellum principles of Just War theory which are concerned with simply the decision to go into war (there are separate principles for conduct in war, referred to as Jus in bello): Proportionality, or the requirement that a state must, prior to initiating a war, weigh the benefits or goods expected to yield from it, over the expected costs (Lazar, 2020); Right intention, which conditions intending to wage war for the purpose of a just cause (ibid); Probability of success, which seeks to prevent a state from waging war if it does not foresee success in its attempt; Last resort, which is defined by stating that the course of action is necessary and there is no better or more peaceful alternative such as diplomacy (ibid); Proper Authority, which I view as having legitimacy from the people the war is waged in the name of; and Just Cause, which is simply a justified reason to go into war, often used in support of a defensive stance against an aggressor. However, there have been instances where humanitarian intervention and other causes are framed as a just cause – I will not delve into those debates here.

If you can imagine that some wars are indeed justifiable given these metrics, then I argue you should also view investing in arms companies as morally permissible. The view that some wars can be justified is one that translates to the view that many states are justified in being armed. Even authoritarian states, can face threats from worse authoritarian states that seek to further harm the wellbeing of a people. However, I do accept that there is a contention that must exist which is that not all countries have a proper authority as a governing force behind a military. We can all think of numerous states who have leaders that appear illegitimate from the point of view of their own people. I do understand the argument not to arm such states, but this is simply an argument for conditional trade in arms, as opposed to full divestment from arms companies.

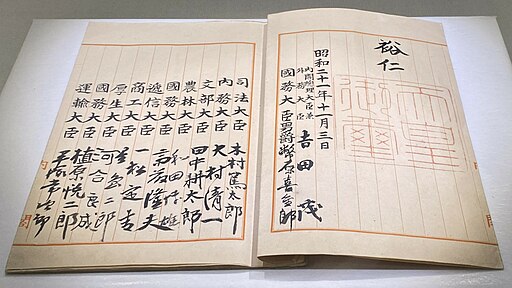

As I hinted above, divestment from all arms companies would have more dire consequences than a case for more transparency and conditionality in the financing and flows of the arms trade. Many people expect their sovereign state to provide them with a public good which is security. Weapons are an integral part of ensuring such a high level of national defence. Let us examine the case of Japan. This great country, that developed a pacifist constitution, namely through its Article 9, has had to evolve past that to ensure some security level is achieved in its territories. Article 9 prohibits the use of force in solving international disputes, the acquisition of military forces and other means of war potential, as well as the right of state belligerency. However, under Japan’s later Legislation for Peace and Security, the use of force is permitted under three conditions (Onuorah, 2020): 1) when an armed attack is against Japan or foreign nations that could threaten Japan’s survival; 2) if there are no other ways to deter such an attack; and 3) the action taken is limited to the minimum extent necessary. This indicates to me that even Japan, which literally has a pacifist constitution, has come to terms with a non-pacifist world, and we should be taking note – as tough as that may be in an increasingly civilized world.

References

Lazar, S. (2020) War, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/war/

Mulla, I. (2024) Exclusive: Cambridge’s wealthiest college votes to divest from Arms Companies, Middle East Eye. Available at: https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/cambridges-wealthiest-college-divest-arms-companies

Neu, M. (2011) ‘Why there is no such thing as just war pacifism and why just war theorists and pacifists can talk nonetheless’, Social Theory and Practice, 37(3), pp. 413–433. doi:10.5840/soctheorpract201137325Onuorah, D. (2020) Is Japan’s defense policy taking an offensive turn?, THE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS REVIEW. Available at: https://www.iar-gwu.org/blog/oo6h3mo5qy895akjv83zwgudjh38n2

Image credits

The Original Text of the Constitution of Japan as of 2023 – source: Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Constitution_of_Japan_2023.jpg