You’d better believe that believers are better.

So far as religiosity is concerned, humanity, say Cooper and Pullig , is divided fairly neatly into three clusters: Skeptics, Nominals and Devouts. The bulk of the evidence suggests that there is a relationship between religiousness and moral reasoning. That relationship, though, is complex. Its anatomy needs a lot of exploration. Cooper’s and Pullig’s exciting and audacious paper, which concerns broadly Christian religiosity amongst marketing students in the US, suggests that narcissism is a factor in explaining why individuals make wrong ethical decisions. That in itself isn’t surprising. Narcissism, for instance, is a predictor of white-collar crime in business: narcissistic individuals tend to think that they are above the laws that govern the behaviour of lesser mortals. What is perhaps surprising is that ethical decision-making was affected by narcissism only in Nominals and Devouts. The reasons for that can be speculated about very entertainingly. But I want to highlight one almost incidental observation: ‘Notably, Skeptics in general exhibit worse ethical judgment than respondents in either of the other two clusters.’

‘Skeptics’, in this context, are ‘low in professed internalization of their religious faith’ and who also ‘largely reject foundational Christian teachings that have been acknowledged by Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Protestant denominations since the earliest days of the Church. The Skeptic’s orientation towards religiosity is largely external, when it exists at all, suggesting that religion is a convenience that Skeptics adopt for social and personal reasons.’

If the ethical judgment of Skeptics (I’ll keep the US spelling) is worse than that of non-skeptics, why might that be?

I suggest that it’s because human minds are built for religious belief (a thesis I’ve articulated at length elsewhere) (1) and that accordingly a mind that doesn’t tend towards belief lacks something that is needed for proper functioning. Poor exercise of ethical judgment is one symptom (no doubt there are others) of that suboptimal working. Note that this doesn’t necessarily imply that the fact of religious belief, let alone the content of a belief, causes ethical judgments to be made well. Causation and correlation are hard to disentangle. Religious scepticism is simply a marker of a type of brain malfunction that makes right ethical decision-making hard.

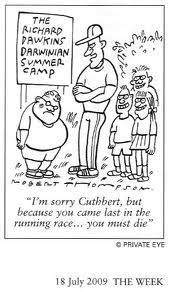

The remark that human minds are built for belief doesn’t begin to mean that I’m espousing some sort of creationism. Heaven knows (if it exists), that I’m about as far from that as one can get. I mean only that we’ve evolved to be believers. Normal brains can’t help but form convictions about things. Our default settings have been fixed by natural selection so that they over-attribute agency to the world.(2) Normally adjusted brains, hearing a rustle in the reeds, will tend to conclude that it’s a lethal sabre-toothed tiger rather than a benign gust of wind. There’s a massive selective advantage in a setting that results in false positives rather than false negatives. One false negative and you’re dead. So we populate the world with personality, meaning and significance. This isn’t a tremendously good explanation for religion itself, in fact (it’s great for poltergeists and for the animistic worship of rocks), but it serves to make the point that we are constitutionally, and from a long time ago, believing animals. If we don’t find that believing comes naturally, it’s because we’ve got a disordered constitution. I don’t know if there’s a remedy.

References

1. C. Foster, Wired for God: The biology of spiritual experience (London, Hodder, 2010)

2. J. Barrett, Why would anyone believe in God? (Lanham, MD: AltaMira, 2004)

Hello Charles,

I know that whatever you write I should hug you as a lawyer as I know that you’re risking damnation on my behalf……

but I don’t find it entirely surprising that a group which simulates religious belief for personal and personal reasons should be less ethical than those who hold beliefs for other reasons. Isn’t simulating a belief in itself a demonstration of unethical behaviour?

(I know that neither you nor the authors use the term “simulation”, but what else could an “orientation towards religiosity is largely external, when it exists at all” mean?)

Interesting thoughts on the Darwinian advantage of religious belief.

As for a remedy, as someone once wrote : “To call on (people) to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.”

Anthony: many thanks.

The study was a very American one. The subjects all seem to have come from a Christian culture to a degree unthinkable in the UK. Accordingly not even the sceptics (who had no Christian doctrinal convictions) felt able to abandon the trappings of the Christian culture. It would be interesting to see if the results were replicated over here, where it’s so much easier to ‘come out’ as a sceptic – indeed where it’s hard not to.

One of the frustrating things about the paper is that the comment about the poor ethical judgment of the sceptics isn’t really discussed. For a blog-writer, though, that’s rather good. It means that there are fewer fetters on the speculation.

C

Charles,

It sounds to me like your argument is: skeptics are more likely to have malfunctioning brains, malfunctioning brains lead to bad decisions, hence skeptics make bad decisions.

We could double check this by seeing if skeptics are also worse in other tasks; most importantly: do skeptics have a lower IQ? If skeptics have a malfunctioning brain, it seems like they should do more poorly than believers on IQ tests.

This is contrary to the evidence though. Atheists have a much higher IQ than believers, and it seems to be roughly linear (the more atheistic, the more intelligent). So I’m not certain I buy your explanation.

(See e.g. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religiosity_and_intelligence)

This really depends on what is meant by “ethical judgement”. The claim seems to presuppose a single uniform code of moral values held by all respondents, but such a code does not exist.

> “Skeptics in general exhibit worse ethical judgment than respondents in either of the other two clusters.”

This really depends on what is meant by “ethical judgement”. The claim seems to presuppose a single uniform code of moral values held by all respondents, but such a code does not exist.

I was wondering the same thing. As I was reading this, I wondered “Did someone quantify morality and not tell me about it?” How do you asses someone’s moral code? There is no test that one can take in order to determine your morality, so how can you conclude in any scientific sense who is more moral?

This also seems to completely ignore people with other belief systems and defines people as either Christian or non-Christian. I don’t know if “unbeliever” is the best word for that. For example, Muslim’s would be “unbelievers.” in this definition.

Ben. Many thanks. But that wouldn’t work as a test of the thesis. A malfunction in one department doesn’t imply a malfunction in all.

C

John: many thanks.

I think that there is a very surprising degree of agreement about what amounts to ethical conduct, but entirely agree that the paper should have been more explicit about the foundations of the claim.

C

Thank you for the reply Charles. If Socrates were to visit our Agora and ask a few questions, it seems to me that he would find considerable disagreement about what is construed as ethical conductand he would find that Thrasymachus is alive and wellin our Agora, were the “Golden Rule” is often interpreted as “he who has the gold, makes the rules”.

I’m not sure about a “surprising degree.”

If you asked “Is murder wrong,” I”m sure everyone would agree that it is. However, if you ask “Is lying wrong?”, some may reply “Absolutely,” others may say “That depends. Is the lie going to harm someone, or is it going to stop harm (ie. a murder intent on killing your friend asks where your friend is)?”

There are thousands of questions that could be asked in this way.

If they asked simple questions (like the muder one above) then virtually EVERYBODY would have gotten them right.

If they asked a complex question (like the lying one) then there is no clear moral answer, and both answers may be correct. A scientific study can’t say what the correct answer is.

To amplify your point, I think it’s worth noting that even the widespread willingness to assent to the claim that “murder is wrong” doesn’t really amount to a substantive moral agreement, because it’s more or less built in to the concept of murder that, for a killing to count as murder, it has to be wrong. Somebody who wishes to defend an intentional killing, such as an execution or a killing in self-defence, will deny that it constitutes murder rather than defending it as a case of acceptable murder. So the agreement that “murder is wrong” just masks the extent of disagreement over when killing is acceptable.

Similar comments, incidentally, apply to the claim that “stealing is wrong”: the notion of stealing presupposes a notion of private property, and the notion of private property is intelligible only if there’s a prohibition against taking other people’s property. So to say that stealing is wrong amounts only to the uninteresting observation that, if somebody has a right not to be deprived of something, it is wrong to deprive them of it.

Certainly a valid point. But isn’t the basis of your post that a malfunction in one department (belief) implies a malfunction in another (ethics)?

Thanks Ben. Sure, but an ability to believe (if not the contents of ones beliefs) and ethics are surely more closely related than are IQ and ethics. Yes, the exact nature of the ethics/belief relationship is obscure (this study hints at that obscurity), but an inability to define the nature of relationship doesn’t mean that the relationship isn’t there.

C

John,

Many thanks. I don’t entirely share your cynicism about the Golden Rule. And it’s hard to find a society where selfishness, cowardice, infidelity, dishonesty, indiscriminate killing and so on are praised. Sure, each society will denounce these things in slightly different terms, but the fact that they all denounce is the really significant thing.

C

> And it’s hard to find a society where selfishness, cowardice, infidelity, dishonesty, indiscriminate killing and so on are praised

But do we need to find a society where such things are openly praised? That seems to be a strawman argument; we only need to find a society that is willing to turn a blind eye to such things. Personally, I am not cynical at all about morality, but I confess that am somewhat cynical about the alleged moral clarity those who claim that “without god everything is permitted”.

Actually, you are kind of making my point…

No skeptic would get those questions wrong. If you asked “Is indiscrimate killing wrong?,” virtually everyone will answer yes.

Yes, but although virtually everyone will answer “yes” many will unfortunately often acquiesce to indiscriminate killing, whether it be be Hiroshima or Dresden….

…as if hypocrisy were never invented, or (possibly) that we can justify anything we wish to.

Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow

John: many thanks. I don’t see that if my argument is wrong, it’s wrong because it’s based on the celebration of a victory over a straw man. All I was pointing out was the anthropologically astonishing ubiquity of a few core ethical convictions. No society turns a blind eye to transgressions against that core. Societies may penalise the transgressions very patchily, or not at all, in their laws, or reward the virtues inconsistently: but that doesn’t mean that they’re ever really abandoning the core.

I bet I’m a lot more cynical than you are about the ‘alleged moral clarity of those who claim that “without god everything is permitted.”‘ If you took my post as some sort of apologetic for the religious Right, you’ve misunderstood me. And if you did, that’s no doubt my fault entirely. C

I am grateful for the opportunity to discuss these issues with you on your forum Charles. It’s fair to say that there are some common features across conventional morality, but for a complete picture we would need to explore this historically. Steven Pinker points out that Rousseau and Hobbes both attempted this survey and both came to opposite conclusions about the default state of humanity. The data Pinker collected makes it clear that Rousseau got it wrong and Hobbes got it right; humanity’s history has in fact been been very nasty and brutish, and the data provides strong evidence that notions of what counts as ethical conduct underwent a substantial revolution a few hundred years ago.

So if I look at a person’s brain while they are considering shoplifting a coke vs. while they are praying in church, the same areas would be active? This seems doubtful to me – could you link a source?

Actually this is an interesting study, but they fail to report a number of characteristics of the samples being studied, notably standard deviations of the different variables being measured. The multi-country study of business ethics done by Peterson et al (J Business Ethics 2010; 96:573-587) specifically addresses the direct effect of religiosity. They conclude that religiosity does significantly predict more ethical responses to their questionnaire, as does gender (women were more ethical) and country. However, they point out that religiosity explained only 2% of variation between individuals, gender 1%, and nationality 3%. If we look at the magnitude of the regression coefficients in Cooper and Pullig Table 2 and Fig 1, they report the total R2 of 11%, and we can guess that Narcissism explains roughly the same amount of variation as religiosity.

That is, religiosity may explain a small amount of systematic differences between individuals, but equal amounts are explained by other factors such as sex and personality. The distribution of self-reported ethicality in highly religious and non-religious almost completely overlap. This is aside from the question of how well pencil and paper instruments given to university students reflect their actual business dealings. Peterson et al mention that the sex difference in ethicality diminishes with age (and presumably experience in the real business world).

I might also note that the ethical questions here are fairly “value neutral”: no tricky questions about homosexuality, abortion, indecent literature, allowing women to work outside the house.

David: very helpful. Thank you. I agree entirely with your comments about the limitations of the study, and will have a look at what Peterson et al have to say. C

Ben: thank you, but no, that wasn’t my claim at all. To say that one multi-faceted faculty will depend to some mysterious degree on another multi-faceted faculty isn’t to say anything whatever about what will light up on a fMRI.

John: thank you again. I agree with everything you say except the final clause of your final sentence. I just don’t see that the historical data support that proposition. Yes, of course morality evolves, but the evolution is at the edges. Previously contentious things become mainstream morality, or are excluded altogether from the ambit of morality. The core remains unchanged.

One false negative and I’m dead. must be my disordered constitution, a closer reading of your post reveals my misapprehension re the gist of the thing though it seems some of your conclusions re the paper were misconstrued. Reading other’s remarks I was pleased to see I am not the only one thrown off the path.

Thought I’d throw in another quote from the paper @ http://www.springerlink.com/content/u0k76hw8x37h7562/fulltext.html

An explanation for the Devout cluster is not so easily hypothesized. There is an inherent contradiction between high levels of narcissism and adherence to Christian orthodoxy that causes these findings to be surprising and to seem counterintuitive. This discrepancy seems apparent because the teachings of Christ make clear believers’ responsibility to put others before themselves, to uphold what is right even in difficult circumstances, and to make ethical decisions in submission to the transcendent authority and commandments of God. Thus, we conclude that the negative impact of narcissism is sufficiently intrusive and powerful that it entices people into behaving in ways inimical to their most deeply held beliefs. In short, the narcissistic Devouts who may choose to exercise their poor ethical judgment would be committing acts that are, according to their own internalized value system, blatantly hypocritical.

Comments are closed.