By Brian Earp

See Brian’s most recent previous post by clicking here.

See all of Brian’s previous posts by clicking here.

Follow Brian on Twitter by clicking here.

This is a rough draft of a lecture delivered on October 1st, 2012, at the 12th Annual International Symposium on Law, Genital Autonomy, and Children’s Rights (Helsinki, Finland). It will appear in a revised form—as a completed paper—at a later date. If you quote or use any part of this post, please include the following citation and notice:

Earp, B. D. (forthcoming, pre-publication draft). Assessing a religious practice from secular-ethical grounds: Competing meta-ethics in the circumcision debate, and a note about respect. To appear in: Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Symposium on Law, Genital Autonomy, and Children’s Rights, published by Springer. * Note, this is not the finished version of this document, and changes may be made before final publication.

* * * * * *

Hello. My name is Brian Earp; I am a Research Associate [Editor’s note: now Research Fellow] in the philosophy department at the University of Oxford, and I conduct research in practical ethics and medical ethics, among some other topics. As you saw from the program, my topic today is the ethics of infant male circumcision—specifically as it is performed for religious reasons.

I should begin by saying that in debates on this topic, I’ve noticed that there is sometimes a very serious reluctance to address the issue of religious motivation directly. And this is true even among those who are otherwise outspoken in their opposition to circumcision on other grounds. For example, in 2007, Harry Meislahn of the Illinois chapter of NOCIRC—a prominent anti-circumcision organization—was asked if he would argue that Jews should discontinue circumcising their babies, along with secular or non-religiously-motivated parents who might be doing it out of a sense of cultural habit, or because they thought it could be good for the baby’s health. He replied: “No. I don’t prescribe for Jews, at all. This is an absolute loser. I’m not Jewish. … I withdraw from this field because it generates lots of heat [and] very little light” (quoted in Ungar-Sargon, 2007).

(He went on to say, however: “I would maintain that a Jewish baby feels pain just as a non-Jewish baby feels pain, and there are Jewish men, just like non-Jewish men, who are real angry that this was done to them.”)

The philosopher Iain Brassington has recently expressed a similar concern. On the Journal of Medical Ethics blog, he wrote: “Though I [have] mentioned the [recent] decision of the German court that ritual circumcision constituted assault, I’ve wanted to stay clear of saying more about it [because] it seemed too potentially toxic” (Brassington, 2012, para. 2)[1]. To give another example, the bioethicist Dan O’Connor from Johns Hopkins University—in an article entitled “A Piece I Really Didn’t Want to Write on Circumcision”—has recently said that: “when [a reporter] calls my work and ask[s] if there is a bioethicist in the house who will give the anti-circumcision viewpoint, I beg off. … I would be a terrible interviewee anyway, [since I would have to preface] my every argument against circumcision with rambling spiels about what loving and caring parents my [Jewish] friends are” (O’Connor, 2012, para. 10).

Finally, as a philosopher colleague of mine wrote to me in a recent email: “To be honest with you, I am strongly anti-circumcision. The reason I don’t [write papers on the topic] is that I have a large number of circumcised Jewish … friends who I think would be offended if they found out [about my views]” (personal communication, May 17, 2012).

Like all of the individuals I have just mentioned, I find myself in the position of being largely skeptical about the moral permissibility of ritual circumcision—for reasons I will give in just a moment—and yet I am well aware that since I myself am neither Jewish nor Muslim, I have an especially good chance of offending someone who is when I subject the practice to critical scrutiny. This chance is, of course, magnified by the fact that circumcision is seen by some as being a central, or even obligatory, ritual in each of these religions. And just like the bioethicist Dan O’Connor and the philosopher-colleague whose email I quoted above, this potential for causing offense extends to many of my closest friends, to colleagues of mine, and to a pretty wide range of people I have no particular interest in irritating.

So perhaps there is a reason to hesitate. Because religious convictions are a deep, and certainly emotionally-charged, aspect of the lives of so many, attempts to question a religiously-motivated practice—especially by one who is not religious, or differently religious—can lead to outcomes that are very far from productive. To illustrate, here is a quote from a comment I received on my Facebook page in response to a post I published on this topic in 2011:

Sorry Brian, you’re entitled to your non-Jewish opinion, but we’ve been doing very nicely for 5,771 years with this ancient tradition of our people. And I don’t even know who the hell you are, but this kind of nonsense just pisses me off. (quoted in Earp, 2011).

So, as I say, sometimes the conversation doesn’t turn out to be as productive as I’d hoped. Part of what I think is going on here, is that we have an unwritten rule in polite society that says that certain ideas or practices are out of bounds for critical discussion. The English humorist Douglas Adams made a similar point in a speech he gave in Cambridge in 1998. Talking about religious customs specifically, he said:

Here is an idea or a notion that you’re not allowed to say anything bad about; you’re just not. Why not? — because you’re not!’ If somebody votes for a party that you don’t agree with, you’re free to argue about it as much as you like; everybody will have an argument but nobody feels aggrieved by it. If somebody thinks taxes should go up or down you are free to have an argument about [that], but on the other hand if somebody says ‘I mustn’t move a light switch on a Saturday’, you say, ‘Fine, I respect that’. (Adams, 1998)

Now, obviously I don’t have any arguments about whether—or when—it’s OK to use a light switch. I do want to focus, however, on this idea about respect. I don’t think it actually is showing respect to anyone to give an automatic pass to anything she says or does just because it might have to do with her religious practice. I think that sort of avoidance has much more to do with fear than with respect—fear that you might upset the person, or fear that you might sound stupid for not knowing more about the custom, or fear that the conversation might turn out to be awkward, or whatever the fear might be.

Respect, it seems to me, is very different from this. Respect has to do with taking certain positive things for granted. In my own experience, for example, I sometimes talk with my Jewish and Muslim friends about my views on the ethics of circumcision. Some of these friends are in agreement with me that ritual circumcision may be, at the very least, morally suspicious; but others hold a different view. Whatever their perspective, however, I respect these friends enough to know that they’ll listen to my arguments with an open mind, really consider what I’m saying, and engage in debate productively. And most of the time, to be sure, they respect me enough to know that I’ll extend them the same courtesy, which I will. Respect is not about avoidance, then, at least in my opinion. It is about the opposite of avoidance—it is about engagement, conversation, communication—so long as these are done in a fair-minded and well-intended way.

I also think that there is something potentially very condescending about the idea that someone’s feelings—religious or otherwise—might be so fragile and irrational that instead of just saying what you really believe, and having an honest conversation about it, you should tiptoe around, and blush, and make excuses, and pretend that you don’t mean what you mean or think what you think. That doesn’t seem like real respect either—and I think my religious friends would be quite rightly insulted if they thought that I was operating out of this kind of mindset when I talked with them about their beliefs and practices.

So, having said all that, in what follows, I am simply going to trust that I can engage directly with the ethical arguments for and against religiously-motivated circumcision, without having to hedge or qualify, or worry about whether I might offend someone for whom this practice is seen as being too sacred to talk about. People are free to disagree with me, of course, and I will be happy to take on board any constructive criticism they may have to offer. I am open to changing my views. But I do want to spend the rest of my time dealing directly with the arguments.

I will start with an argument against religiously-motivated circumcision, and then I will consider some common objections.

The premise of my argument is this. As a rule, it should be considered morally impermissible to sever healthy, functional tissue from another person’s body—perhaps especially if the tissue cannot “grow back,” and even moreso if it comes from the person’s genitals—without first asking for, and then actually receiving, that person’s informed permission.

Now, ordinarily, and with respect to almost every case we could imagine, this would count as a foundational ethical principle. It does presume that the individual is an appropriate unit for moral analysis; it does presume that individuals have certain rights, among which is the right to bodily integrity; and it does presume that the infringement of that right can only be permitted under conditions of informed consent (or in circumstances like a medical emergency).

Of course, someone could question or even deny any one of those presumptions, but then they would have to come up with a better way to ground their own moral theories that didn’t inadvertently create a justification for having parts of their body cut off without their permission. I’m not saying this is impossible, but it’s something to look out for. And actually, I think there is a competing meta-ethic hidden within religious defenses of circumcision—and it’s one that downplays the relevance of the individual, and specifically the individual as a child, to independent moral consideration—but I will come onto that point a little bit later on.

For now, let us assume that the ethical premise I’ve given is a reasonable one, and let’s take it for granted to see what follows. Well, since ritual circumcision involves the removal of healthy, functional, erogenous tissue from the genitals of a newborn or young child, and since babies and young children are incapable of giving meaningful consent to such a procedure, our principle is obviously violated, and therefore circumcision is unethical on this theory.

Now, this is not just abstract philosophy. As most of us know, a recent decision by a German court in Cologne—which said that ritual circumcision is a form of assault—relied on ethical reasoning very similar to what I have just laid out. And as we also know, this conclusion was not very readily accepted by a large number of religious leaders within Judaism and Islam, and even within some corners of Christianity. This last part should be a little surprising, of course, since the founder of Christianity—Paul (or Saul) of Tarsus—was explicitly and even energetically opposed to the practice of circumcision, as he made very clear in his letters to the earliest Christian churches. And, as Sami Aldeeb pointed out in his speech yesterday (see Aldeeb, 2012), this was the official church position for a pretty long time.

But, leaving that aside, what this reaction to the Cologne decision means is that we can look at some objections to the argument I have given that are not just hypothetical, but that have actually been given—and very recently—as serious attempts to defend ritual circumcision against the charge that it is an unethical practice. And I would like to consider a few of these objections one at a time.

The first objection is that religious circumcision is an ancient tradition, and one that is felt to be very important to the practice of Judaism or Islam. For example, Dieter Graumann, the president of the German Central Council of Jews, has said, “Circumcision of newborn boys is a fixed part of the Jewish religion and has been practiced … for centuries” (quoted in Hall, 2012). He then went on to criticize the Cologne ruling as being “outrageous” and “insensitive.” An Islamic representative, Ali Demir, made a similar point: “this is a … procedure,” he said, “with thousands of years of tradition behind it and [a] high symbolic value” (ibid.).

Now, as I was preparing this talk, I wondered about whether I should count these sorts of statements as being actual “objections” to the ethical case made by the German court. Seemingly, it should go without saying that something’s having been done for a long time does not in any way amount to an argument for its moral permissibility. The thing might actually be morally permissible, of course, but this just wouldn’t be the way to show it. The more I thought about it, however, the more I came to believe that I couldn’t just pass over the “ancient tradition” argument as a sort of a straw man. This is because this exact line of reasoning has been repeatedly cited in recent weeks, by a number of influential religious leaders, in a seemingly sincere attempt to shape public discussion on this topic. So I need to spend a little bit of time responding to this view, with what would otherwise be a statement of the obvious:

Many practices that are now regarded as being very clearly unethical had been going on for an extremely long time before anyone had the idea to question them. Examples include slavery, footbinding, the cutting of female genitals, and beating disobedient children with sticks. Usually these practices persisted without much alarm for one of two reasons. Either the moral standards that they would eventually be seen as violating had not yet had been developed, or those standards did exist for other cases but just weren’t commonly seen as applying to the practice itself until enough people sat down and made the connection. I think what’s happening right now with circumcision is not so much the first of these, but more the second. In other words, the relevant ethical principles—about bodily integrity, consent, protecting the vulnerable in society, and so on—have been available to us for quite some time now. It’s just that we’re so used to circumcision as a cultural habit, that many people fail to see how patently inconsistent this practice is with the rest of their own moral landscape.

My colleague Anders Sandberg has given an argument for this view that I think is worth considering in a little bit of detail. He writes:

It is interesting to consider a fictional case: suppose I come up with a religion that claims [that] male nipples are bad, and should be removed in infancy in order to prevent various spiritual and medical maladies, as well as showing faith. I have no doubt that getting this new practice approved anywhere would be very hard, no matter how much I and my adherents argued that it was a vital part of our religion. No doubt arguments about unnecessary mutilation and infringement of children’s self determination would be made, and most would find them entirely unobjectionable. If my religion joined the chorus of religious critics to the German decision it is likely that the others would not appreciate our support: after all, they do not want approval for all religious surgery, just a particular one. And nobody likes to be supported by an embarrassing supporter.

But this seems to suggest that what is really is going on is [a] status quo bias and [something about] the social capital of religions. We are used to circumcision in Western culture, so it is largely accepted. It is very similar to how certain drugs are regarded as criminal and worth fighting, yet other drugs like alcohol are merely problems: policy is set, not based on actual harms, but … on a social acceptability scale and who has institutional power. This all makes perfect sense sociologically, but it is bad ethics. (Sandberg, 2012)

Now, I don’t think that Anders’ scenario is completely water-tight, and I don’t think that a theologically sophisticated religious person would find the “male nipples” example to be an appropriate or a complete analogy. But I do think that Anders is onto something when he suggests that if the “ancient tradition” objection does carry any weight in this conversation, it is for sociological reasons rather than ethical ones. In fact, I don’t see that this objection does any argumentative work for the defender of religious circumcision: It might work as a rhetorical strategy to affirm the social capital of his religion, but it isn’t an argument.

OK, I would like to move on to a second objection that I have heard a number of times in response to the Cologne decision, and one that is potentially a little harder to deal with. This objection is that circumcision is divinely mandated and hence obligatory for religious Jews and, according to some interpretations, maybe Muslims as well. In Judaism, as we all know, the mandate is even specific about the exact timing of the procedure: according to the book of Genesis, the baby’s foreskin must be removed on the eighth day after birth. And this timing is, according to a number of vocal religious commentators, quote, “non-negotiable.”

I want to start with this idea about non-negotiability. My first question is, according to whom? Certainly people like Dieter Graumann, the president of the German Central Council of Jews I mentioned before, has repeated this claim (see, e.g., Gedalyahu, 2012). And so have a number of influential, usually conservative or Orthodox Jews, some of whom have been saying some very authoritative-sounding things on behalf of, quote, “the Jewish people” (see, e.g., Harkov, 2012). But this seems to me to be somewhat disingenuous. As anyone who knows any actual Jewish people can attest, “the Jewish people” is not a collection of uncritical sheep who all think the same thing. “The Jewish people” do not uniformly adhere to the exact same theology. And, specifically, “the Jewish people” includes a large and growing number of individuals—including, in my view, individuals with exceptional moral insight—who simply do not believe that circumcision is a “non-negotiable” component of their religion (e.g., Goldman, 1998; Goodman, 1999; Glick, 2001; Milgrom, 2012; Pollack, 2013; Sadeh, 2013; Ben Yami, 2013; Ungar-Sargon, 2013; Steinfeld, 2013)[2]. I suppose someone could argue that certain conservative representatives within Judaism are theologically correct, and everyone else is deluded, but that would take a lot of time and energy and it would be an argument that would probably fail to convince anyone who didn’t already hold that view. Also, it would be much harder to express as a simple axiom, which is what the newspapers seem to appreciate. So instead we are confronted with a string of public declarations that make it sound like Judaism a monolith and that there are no meaningful debates to be had about the religious requirements implied by certain passages within the Torah.

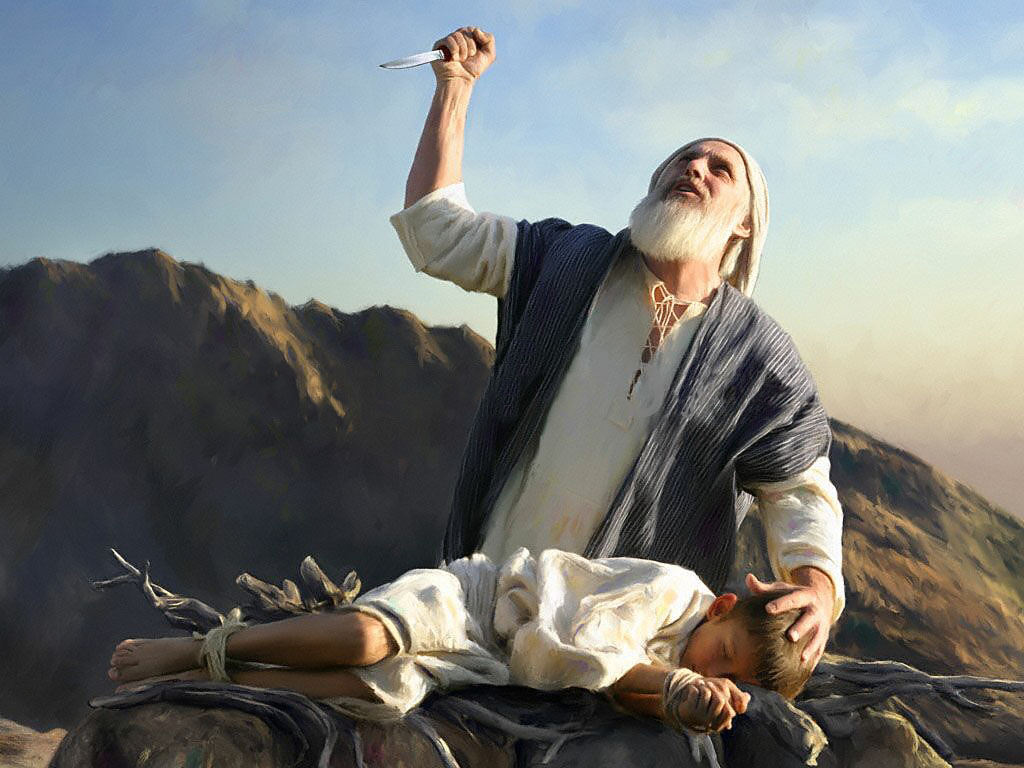

Another point is this—and, again, I wish I were attacking a straw man here, but based on the mainstream, public debate I have seen going on in the last few weeks, I feel that some very basic points about the philosophy of religion need to be brought up as reminders. First, even though a person or a group of people may sincerely believe that a given practice is divinely mandated, it doesn’t necessarily follow that it is divinely mandated. Second, even if something really is divinely mandated, it doesn’t necessarily follow that it is non-negotiable. Third, even if something is felt to be non-negotiable, it doesn’t necessarily follow that it is morally permissible. And this brings us very quickly to the classic dilemma about what you’re supposed to do when God tells you to do something unethical.

We all know the puzzle about Abraham and Isaac: God tells Abraham that he must sacrifice his son. So what should Abraham do? There are a couple of well-known possibilities in logical space here. One option is that Abraham should assume that he’s misunderstood something. Since killing innocent children is unethical, and since God is a morally perfect being, God must not really have said that. Another option is that he starts to wonder if maybe he wasn’t really talking with God after all, but maybe it was Satan, or maybe just a voice in his own head. Or he can conclude that God is not as morally developed he used to think, or is even a source of evil. Whichever way he chooses to go, the correct answer from an ethical perspective is: No, I will not kill my son.

Obviously a lot of people have looked at this case over the centuries, and I’m not the first one to give the analysis you just heard. As a number of commentators have noticed, there is a pretty big conflict in this story between the requirements of morality and the requirements of the divine mandate. Kierkegaard (1843) thought he could solve the puzzle by talking about the “teleological suspension of the ethical.” This is the idea that we should use our faith to rise above mere ethics and morality and enter into a higher, and more absolute relationship with the divine. Now I think that this is a very dangerous thing to propose. And I think it has real consequences, one of which is that the religiously-motivated suspension of morality has been a source of a lot of suffering, for a lot of people—including marginalized and vulnerable people—for a very long time.

But my sense, in fact, is that the large majority of contemporary religious believers don’t actually do this. What I mean is, when something is felt to be unethical, what they actually do is one of two things. Either they revise their understanding of what is divinely required in the first place; or else they engage in some very complicated psychological maneuvers—many of them unconscious—that lead them to conclude that the thing must not be unethical after all, even though it really looks like it is from every other perspective. So for circumcision, for example, they might downplay the harms, risks, and drawbacks of the procedure; or they might use euphemisms like “snip” or “flap of skin” when they talk about what it is that is being cut off; or they might emphasize the postulated health benefits (while ignoring disputes over their scientific credibility); or they might exaggerate the differences with female genital cutting, or exaggerate the similarities to vaccination, or whatever: a whole range of strategies that make it seem like circumcision isn’t so bad to begin with.

I have seen one major exception to this approach, however. And this comes from an interview conducted by the filmmaker Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon (see Ungar-Sargon, 2007). The clip starts with an Orthodox Rabbi named Hershy Worch talking about circumcision. He says:

It’s painful, it’s abusive. It’s traumatic, and if anybody who’s not in a covenant [with God] does it, I think they should be put in prison. I don’t think anybody has an excuse for mutilating a child. … Depriving them of [part of their] penis. We don’t have rights to other people’s bodies, and a baby needs to have its rights protected. I think anybody who circumcises a baby is an abuser, unless it’s absolutely medically advised. Otherwise – what for … ?

After a moment of what I interpreted as stunned silence, you can hear Eliyahu ask a pertinent question:

How does this covenant alleviate your ethical responsibility that you just so articulately posed? How is it that being in this covenant exempts you from that term … How can you not call yourself an abuser?

The Rabbi actually cuts him off and says:

I’m an abuser! I do abusive things because I am in covenant with God. And ultimately God owns my morals, he owns my body, he owns my past and future, and that’s the meaning of this covenant – that I agreed to ignore the pain and the rights and the trauma of my child to be in this covenant.

Now, I must tell you that—in an important sense—I have a lot of respect for this Rabbi. I think that his statements reach a level of honesty, and accuracy, and even Kierkegaardian philosophical consistency, that has otherwise been lacking from the public conversation on this issue. Here is someone who acknowledges, without hedging or qualification, that he is mutilating the penis of an infant. But he doesn’t take this knowledge as an excuse to go back to his scripture and re-interpret the original commandment, nor does he allow himself to believe that circumcision is a harmless little snip. He just doesn’t resolve the dissonance. Instead, he takes responsibility for his religious commitments, as well as for his behavior—and I think that in doing this, he gives us a rare and unmediated example of the power of religious belief to justify (what the Rabbi himself acknowledges is) the painful assault of a child.

So what should we do with this? I started with the idea that it should be considered morally impermissible to remove healthy, functional tissue from another person’s body without obtaining that person’s permission. And since circumcision violates that rule, I said it was unethical. Then I tried to show that the “ancient tradition” objection doesn’t get us off the hook, nor do the points about circumcision’s being divinely mandated or non-negotiable. So at this point, it seemed like we should be able to stick, at least provisionally, with the conclusion that circumcision is indeed a morally impermissible act.

But now we have something different. Now we have this idea to think about that maybe there’s something bigger than ethics – something like this direct relationship to the divine.

I said at the beginning that I thought there was a hidden meta-ethic behind religious defenses of circumcision, and I think that now we’re beginning to see what it might be. I think it’s this idea that an individual human being, such as a child, is not really the ultimate object of moral analysis. Instead there are other obligations, obligations that come from a community identity, from concern about historical continuity, or ritual continuity; obligations that come from a special covenant between a god and a group of people. And the effect of all this is that the individual child becomes a sort of non-entity. His body becomes not his body. His pain becomes an instrument in fulfilling a higher purpose.

And so, I think before we can get anywhere in this discussion, we are going to have to acknowledge that that is a very different meta-ethic. I think we have to acknowledge that certain religious commitments are based on a particular view of the universe, and that this view is in direct conflict with a “Western” moral focus on: individuals, on human rights adhering to those individuals as individuals, and on the notion that children and infants, above all, need special protection because they can’t defend those rights on their own.

I don’t have a good answer to this conflict. Obviously one can, in theory, adopt any meta-ethical view under the sun. One can adopt a view that says that parts of children’s bodies may be removed without their consent, if that is what a god requires; or one that says that animals should be set on fire and burnt at the altar (again, if that is what a god requires); or one that says that sparing the rod will spoil the child; or that our daughters should be stoned to death if they disobey, or whatever we want. All of these views are logically possible, and many of them are historically accurate. Many of them find direct textual support as well in the holy books of major religions.

But that isn’t how we tend to think about things in modern, Western societies; and it isn’t how we’ve set up our laws. We have a different sort of worldview that we use to make sense of concepts like individual rights, including the right to bodily integrity. So the idea I want to leave you with is this. If we think that there is any chance that we should give up these basic concepts—so that we can defer to a worldview that says that things like community identity are more important than individual identity (and the right to decide what happens to one’s own flesh)—then we’ll have to pay the price of that choice and face it honestly. And that means that the very same individuals who are asking for the religious freedom to perform circumcisions in a secular society, might have to be prepared to give up their own right to complain if someone wanted to cut off a part of their body, or interfere with their genitals without their consent. That is, as I say, a logically possible universe. But it isn’t one that I would want to live in, and I am not convinced that you can have it both ways.

References

Adams, D. (1998). Is there an artificial god? Digital Biota 2. Lecture conducted from the University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. Available at: http://www.biota.org/people/douglasadams/.

Aldeeb, S. (2012). Islamic concept of law and its impact on physical integrity: comparative study with Judaism and Christianity. 12th Annual Symposium on the Law, Genital Autonomy, and Children’s Rights. Lecture conducted from Helsinki, Finland. Text available at: http://blog.sami-aldeeb.com/2012/10/01/conference-in-helsinki-30-september-2012-oral-version-on-circumcision/.

Ben-Yami, H. (2013). Circumcision: What should be done?. Journal of Medical Ethics, 39(7), 459-462.

Brassington, I. (2012, July 17). More on circumcision in Germany. Journal of Medical Ethics blog. Available at: http://blogs.bmj.com/medical-ethics/2012/07/17/more-on-circumcision-in-germany/.

Earp, B. D. (2011, August 26). On the ethics of non-therapeutic circumcision of minors, with a post script on the law. Practical Ethics (University of Oxford blog). Available at: https://blog.uehiro.ox.ac.uk/2011/08/circumcision-is-immoral-should-be-banned/

Gedalyahu, T. (2012, July 3). Berlin hospital suspends circumcisions. Israel National News. Available at: http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/157454#.UHxey46RMV0.

Glick, L. B. (2001). Jewish Circumcision. In Understanding Circumcision (pp. 19-54). Springer US.

Goldman, R. (1998). Questioning circumcision: A Jewish perspective. Boston: Vanguard publications.

Goodman, J. (1999). Jewish circumcision: an alternative perspective. BJU international, 83(S1), 22-27.

Hall, A. (2012, June 27). Religious groups outraged after German court rules circumcision amounts to ‘bodily harm.’ Daily Mail Online. Available at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2165431/Religious-groups-outraged-German-court-rules-circumcision-amounts-bodily-harm.html.

Harkov, L. (2012, August 22). German rabbi circumcision case sparks outrage. The Jerusalem Post. Available at: http://www.jpost.com/JewishWorld/JewishNews/Article.aspx?id=282134.

Kierkegaard, S. (1843/1946). Fear and trembling. In R. Bretall (Ed.) A Kierkegaard Anthology. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Milgrom, L. (2012). Can you give me my foreskin back? Open letter to Bent Lexner, Chief Rabbi of Denmark. Originally published as ‘Kan du give mig min forhud tilbage?’ in the Danish Daily Politiken. English translation available at: http://justasnip.wordpress.com/2013/01/19/can-you-give-me-back-my-foreskin-full-translation/.

O’Connor, D. (2012, September 14). A piece I really didn’t want to write on circumcision. BioethicsBulletin.org. Available at: http://bioethicsbulletin.org/archive/piece-i-didnt-want-to-write/.

Pollack, M. (2013). Circumcision: Gender and Power. In Genital Cutting: Protecting Children from Medical, Cultural, and Religious Infringements (pp. 297-305). Springer Netherlands.

Sadeh, E. (2013). Circumcision from the perspective of protecting children. Available at: http://www.savingsons.org/2013/06/circumcision-from-perspective-of.html.

Sandberg, A. (2012, June 28). “It is interesting to consider a fictional case …” [Web log comment]. Posted to: Earp, B.D. (2012, June 28). Of faith and circumcision: Can the religious beliefs of parents justify the non-consensual cutting of their child’s genitals? Practical Ethics (University of Oxford blog). Available at: https://blog.uehiro.ox.ac.uk/2012/06/religion-is-no-excuse-for-mutilating-your-babys-penis/.

Steinfeld, R. (2013, Noveber 26). It cuts both ways: A Jew argues for child rights over religious circumcision. Haaretz. Available at: http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/the-jewish-thinker/.premium-1.560244.

Ungar-Sargon, E. (Producer and Director). (2007). Cut: Slicing through the myths of circumcision [Film]. Los Angeles: White Letter Production Studios.

Ungar-Sargon, E. (2013). On the impermissibility of infant male circumcision: a response to Mazor (2013). Journal of Medical Ethics, doi:10.1136/medethics-2013-101598.

[1] Just as with Mr. Meislahn, he did nevertheless go on to say more. See: http://blogs.bmj.com/medical-ethics/2012/07/17/more-on-circumcision-in-germany/.

[2] Some of these articles were published after the present lecture was delivered. They are cited here simply to give an indication of some of the most recent Jewish voices opposed to circumcision.

_________________________________________

See Brian’s most recent previous post by clicking here.

A clearly-written/delivered piece, Brian. It baffles me how often people accede to the appeal to tradition, still. Our petty brains still struggle to overcome the biases implanted. If nothing else, practical ethics is a method or tool to constantly fight that appeal, by trying to see as much of reality as possible (perhaps it’s just “the” scientific method?). Orwel was right: it is a constant struggle to see what is right in front of one’s nose — especially when it makes us uncomfortable. Yet, if comfort was a measure of truth, only an elite few would be considered free people today. Thanks for putting this up.

*Orwell

Simply want to say your article is as surprising. The clearness for your post is simply excellent and that i could think you’re an expert on this subject. Well along with your permission allow me to grab your feed to stay up to date with imminent post. Thank you 1,000,000 and please carry on the rewarding work.

A friend of mine wrote the following on my facebook page re: this post:

“I love it; I wish you went more into detail about your point at the end. It felt a little to me like “Sure, there COULD be infinite possible metaphysics but surely we all agree that one is right.” But why? I thought the most compelling part of the argument was that to accept that circumcision is justified is to accept that all non-consensual removing of body parts is justified (once you get rid of the divine mandate and the historical tradition arguments, which I thought you did rather nicely).”

To which I responded:

“Yesssss I agree with you. I finished the lecture at 3AM of the day it was to be delivered, and the bulk of the actual philosophy is left to do. That’s why this is just a ‘rough draft’ and I gotta now get into the nitty gritty before I can publish this as an actual paper …. I think my argument is to be that anyone who enjoys the fruit of secular societies built on “liberal ethics” — in other words who has their own choices respected, who is free from violence against their own person, who can prosecute cases of assault when they themselves are the victim — can’t glibly dismiss these ethics as soon as they enter the church or a synagogue. Make your choice. If you want to live on an island with your co-believers and construct your society on a “community” ethics by which issues like protecting children and preserving bodily integrity are seen as too narrowly “liberal” for your moral imagination — go for it — but we will put pressure on you from our vantage point … So it’s not really saying “Western secular liberal ethics are the best, and your ethics suck” — it’s saying, “You, by participating in a society built upon these ethics, and reaping those benefits, implicitly acknowledge that YOU think these ethics are better, that YOU benefit from them, and therefore YOU must follow their implications all the way through and stop cutting your children.”

Great article Brian, I personally have never read such a clear criticism of historical justifications that wasn’t based roughly along the lines of “they are stupid so therefore are stupid”

However I do have one problem with your final paragraph in the comment above. As equally as Jewish babies don’t choose to grow up in a Jewish community, Jewish adults didn’t choose to grow up in this society. Furthermore, you just cited social isolation as a reason for these practices to continue unchecked, and yet proposed it as a solution (probably not seriously) to wanting to avoid the Western secular liberal ethics. That would imply to me that there is no real way to avoid secular ethics, that in your opinion, isn’t part of the problem in the first place. Even if a group did decide to form an island community based on their beliefs, wouldn’t they just become that “isolated community with beliefs that involve harming their children”? In your argument there isn’t really a way out that I can see.

So I guess I am saying that by citing people “choosing” to live in a Western secular society you are really not being honest to your own stance, primarily that Western secular is the logically and practically decided system of ethics, and that there is no ethical way to exist outside of it. If they did, they would be those dogmatic social isolates.

Of course that brings up the issue of whether or not Western Secular ethics is truly ethical (which by your own examples it hasn’t always been), but that is I suppose more theoretical than practical, and safe to say based on societal agreement of what is right.

Sorry if that was messy, I am new to the ethics game.

Steve – I really appreciate your reply. That’s a great point. All I’ll say is that posting a rough draft of a paper turns out to be a really good idea, because then smart people can point out the holes in your intended argument and you can go back to work on it some more. I think I will have to come up with a more robust defense of secular ethics. Or perhaps a better approach would be to consider, not which ethics is metaphysically more sensible, but rather, to which set of ethics must the state refer when it considers what practices to allow in a multi-cultural secular society. And maybe it’s more this relationship of the state to the two sets of ethics that’s going to have to be the thrust … What do you think?

Brian wrote: ““You, by participating in a society built upon these ethics, and reaping those benefits, implicitly acknowledge that YOU think these ethics are better, that YOU benefit from them, and therefore YOU must follow their implications all the way through and stop cutting your children.”

Well… much as I’d like to agree I don’t think I can. I’d like to argue to Occupy types that “You, by participating in a society built upon these ethics, and reaping those benefits, implicitly acknowledge that YOU think these ethics are better, that YOU benefit from them, and therefore YOU must follow their implications all the way through and [endorse the broadly liberal set of policies we see around the OECD.]” Where the bits in the square brackets are the replacement I’d make.

But I’m not sure the argument works, since the Occupy person may reasonably counter in at least two ways: (1) I did not choose this community in some histroically decontextualised process by selecting from a policy smorgasboard: I was born here, and this is *my* community, too (and among the ethical commitments we cherish is tolerance of minority views); (2) I can prefer this society overall without needing to buy, in toto, the dominant ethical/policy paradigms.

PS – topic changed to choose something safe and uncontroversial, rather than circumcision 🙂

Dave, a great reply. You raise a cogent objection when you say:

“(1) I did not choose this community in some histroically decontextualised process by selecting from a policy smorgasboard: I was born here, and this is *my* community, too (and among the ethical commitments we cherish is tolerance of minority views); (2) I can prefer this society overall without needing to buy, in toto, the dominant ethical/policy paradigms.”

So what do you think I can do to get out of this bind? I guess one possibility is that I could make an appeal to the religious person’s own intellectual and emotional consistency. Because it seems to me that most religious people — who aren’t completely separatist/literalist/fundamentalist — don’t just ‘tolerate’ the wider secular ethics in a society in which they did not happen to choose to live in a historically decontextualized way, but in fact AGREE with it and ENDORSE it, with respect to their conduct of every other part of their lives, with respect to their active and considered participation in the wider society, etc., EXCEPT when it comes to this one custom. You can see the conflict WITHIN the religious person if you’ve ever watched a religious circumcision ceremony. The baby is screaming. The mother is very often in tears, with some profound sense that something doesn’t feel right about what’s going on. Holy words are chanted. Soon enough it’s over, and baby starts to recover from the shock. … Now, I suppose someone could say that intellectual and emotional and ethical consistency aren’t as important as other considerations, and I can see certain arguments to that effect. So it occurs to me that this whole ‘debate’ is really stuck in social-psychological considerations: the mothers FEEL the harm, and there’s utterly no other situation in which they would tolerate a group of men taking their child from their arms and cutting into him with sharp instruments against his will (unless it were needed to save his life). If enough people – secular and religious alike – can make an intellectual-psychological path available for getting from that first instinctual realization to the idea that maybe this custom isn’t necessary, then I expect change can happen. Again — ANY amount of torture could be justified if you could tie it to some “higher-level” gain … this is how I think Alvin Plantinga ‘solves’ the Problem of Evil. He says, well, if the universe were constructed such that all this pain and suffering and misery and death and violence and torture and hurricanes and so on … were some how INSTRUMENTAL to a higher moral good seen from a God’s eye perspective, then a morally-perfect being would actually have to allow for such suffering. I get it. I see that these types of arguments are logically consistent. But that’s why I think we have to get away from theology and morality based on religion. Because it allows us to construct world views that dismiss the problem of suffering, or that even build pantheons to pain and despair. My concern is that if an individual person wants to go through any amount of pain and suffering and loss because they think that this will gain them favor with the deity, or that it will make sense in a cosmic afterlife, or whatever it is, they are free to do so. My toleration for this line of thinking, though, ends very abruptly when that pain is inflicted on someone else against their will. Can I defend this position by appealing to anything other than secular, Western, rights-based, individualistic ethics? I don’t know. That’s my goal. But I need some help making the argument …

Hi Brian, thanls for the reply. I’m afraid I don’t have any words of wisdom to help. I think your reply throws up lots of issues, one of which is the practical (political?) issue of winning hearts and minds vs the theoretical one of winning arguments, and another of which is the ethical limits of tolerance.

On the first I think you probably can trap people into violating consistency reasonably easily by asking them questions about ethics in some analogous principal-agent situation, getting them to commit heavily to the framework you want, and then springing the circumcision example on them. Then – if it’s anything like my experience arguing with people who have strong religious or political commitments – you’ll get the “that’s completely different” response and waves of anger. Maybe you’ve won the argument (at least as assessed by uncommited third parties) but you’ll have irritated them rather than persuaded them, and they can just reorder their ethical priorities to iron out the kinks. Maybe that’s valuable when there are lots of uncommited third parties are around whose support you need. But maybe not. I think your best practical bet is by offering as much support and intellectual ammunition as you can to people who agree with you who live within the relevant communities. But that won’t be won by a one punch philosophical argument, as I know you know. I guess I’m saying I think it’s less about philosophy and more about negotiation and understanding the priorities of other communities.

On the second point I think there are a bunch of issues about tolerance that don’t get much airtime. Generically, of what should we be intolerant in liberal democracies? It seems to me that we should be intolerant of some things: self-contradictory arguments, evidentially empty claims, totalitarian radicalism, perhaps… you outline something you think we should be intolerant of: inflicting injury on someone against their will, regardless of the historical precedent for that. Is there a theory that can describe the circumstances under which liberalism obliges us to be intolerant? [If anyone knows of a good book on intolerance, I’d love to know!]

Dave, once again I’m very grateful for your feedback. Your points do reinforce the idea that what’s going on here is social psychological more than anything, and that a lot of people aren’t going to budge on this issue through strength-of-argument. It’s like Jonathan Haidt’s famous point in “The Emotional Dog and its Rational Tail” – which I assume you’ve come across but if not: http://www.nd.edu/~wcarbona/Haidt%202001.pdf

Of course, at the same time, certain people (like myself) have budged quite a lot on issues through having come across good arguments that made me reconsider my unreflective commitments to certain ideas or practices. There’s clearly room for a range of approaches. People who are skilled at activism, and making emotional appeals, and framing this issue in terms of the pain — they’ll make headway on that front. Hopefully, if I keep getting good feedback on these arguments from thoughtful people like you, then I’ll be able to make some headway on the ‘argument’ front and change some minds that way. There are some very big issues at play — the question of what should liberal societies be intolerant of is HUGE. My favorite quote (recently discovered) on this is from the British general Charles Napier when he was in India, regarding the custom of immolating widows:

“This burning of widows is your custom; prepare the funeral pile. But my nation has also a custom. When men burn women alive we hang them, and confiscate all their property. Let us all act according to national customs.”

Hi Brian, on the point of what persuades different folks – I read a book called Changing Minds by Howard Gardner (an academic psychologist). It’s written for a general audience and is a bit light, but it’s still pretty interesting. He points out that rational arguments persuade some people and some communities (fairly homogeneous ones which happen to place high weight on reason) but won’t persuade in settings with more intellectual diversity (diversity of belief, varying attachments to reason etc). It might be useful to have a read of that since I thought it gave some nice pointers on what might work for practical change with different communities.

As for intolerance – I kind of think we have to be a bit more intolerant of fatuous opinions. The media often feel obliged to give equal time to opposing points of view, even when all the experts say one thing. It would be constructive to work out how to filter signal from noise without re-energising the worst of elitism in “authority”.

I think I should clarify that

“If they did, they would be those dogmatic social isolates.”

I actually meant that to appear more like:

“If they did, would they not become what you described as dogmatic social isolates?”

and is supposed to be more of a question that a statement of my own position. See? New to this.

high-octane horsepower, Brian… let’s see your critics answer it with intelligence. thank you.

“The reason I don’t [write papers on the topic] is that I have a large number of circumcised Jewish … friends who I think would be offended if they found out [about my views]”

That describes perfectly why I do not publish my writings critiquing circumcision, why my intactivist comments on the internet are always pseudonymous, and why I do not prosletyse much amongst pregnant mothers.

I am a Christian of sorts, in good part for Burkean reasons. I did not baptize my children, because my opposition to circumcision has led to oppose infant baptism as well. I do not believe that unbaptised are damned. I do not believe that there is a valid Islamic reason to circumcise, as the Koran is silent about the practice. I believe that Judaism and Islam could both adopt the rule that a man need not be circumcised until a few months before a religious marriage. To choose circumcision for oneself, whether out of faith or tribal loyalty, carries a great deal of existential meaning. To impose circumcision on a screaming child has no religious meaning for the child.

At least half of those who describe themselves as Jewish have no valid religious reason to circumcise their sons either. Many Jews are atheists/agnostics, or squirm at the phrase Chosen People, or do not really believe that they descend from Abraham, or deem the Covenant a myth. Circumcision around the world is mainly performed because the parents believe that the sort of women they would like their sons to marry will make a face when they discover that their adult son does not have a penis that is bald 24/7.

The bald penis is a status symbol, a cattle brand, a marker that one was born into the right sort of family. Circumcision is the biggest problem in the social psychology of human sexuality.

Mr O’Connor, the ethicist at the Bloomberg School at Johns Hopkins, cannot speak the truth as he knows it, without deeply antagonising powerful colleagues at Bloomberg and in the Faculty of Medicine. This is one of the many reasons Jewish intactivists are the most valuable intactivists. In this regard, I especially want to praise the writings of Miriam Pollack.

Mr Moosa did well to quote Orwell: “it is a constant struggle to see what is right in front of one’s nose — especially when it makes us uncomfortable.”

You write well and your words are appreciated. I liked this especially. “The bald penis is a status symbol, a cattle brand, a marker that one was born into the right sort of family. Circumcision is the biggest problem in the social psychology of human sexuality.”

Circumcision is the mark of your parent’s fear and ignorance. In ancient times, being cut off from the tribe of Jewish nomads would likely have meant death. Circumcision was a way of making men docile, manipulable in the hands of priests and Rabbis. It made sex pleasureless, and reduced it from a transcendent experience, to something mundane, needed only for reproduction. Religion would not have to compete with sexual desire, if you can make it mundane, and circumcision does make it so.

As someone born to a Jewish family I am royally pissed off that my genitals were mutilated and compromised for the “tribe’s” benefit. The whole thing is a blight on Judaism, undermining any pretense of ethics that could be presented. I urge you to continue writing and speaking and to consider using your name in doing so.

Religious circumcision is a legacy from the time, namely all of human history until the last half century, when the human understanding of sexual acts and the sexual organs was extremely limited. A woman was first clinically observed having an orgasm in 1954. Contraceptive pamphlets were deemed obscene until the 1930s. Premarital sex, now taken for granted, was widely seen as a grave moral problem until the 1960s. When I was a teenager in the 1960s, Time and Newsweek frequently reminded readers that there was a clitoris and that it was the locus of female pleasure. Until about 1990, female masturbation was taboo in the USA. I am not surprised that the male foreskin came to surrounded with all sorts of myths and misunderstandings. Overcoming circumcision requires that circumcising cultures admit that they have much to learn about sex and genitalia. It is easier for women to admit their ignorance about the male parts. Maybe this is why most intactivists are mothers of childbearing age.

Human history is about 200 000 years old (if you don’t happen to be a young earth creationist) so claiming

is almost wrong. The oldest, written evidence for Jewish live dates back to about 700 before Zero, afaik. The Egypt’s practiced it before, and I heard of old findings, maybe 7000 years old.

So most of the time, 96% probably, circumcision was not performed on earth by man. In some regions never until our modern times.

There is a contradiction at the heart of the current defences of religiously-motivated circumcision. On the one hand the claimed right of parents to circumcise their children is based on the principle of individual freedom to religious belief and practice, as accorded by the European Enlightenment and subsequent developments in human rights, such as the various United Nations declarations and conventions. On the other hand, circumcision as a cultural practice arose in pre-Enlightenment times, in patriarchal, tribal, monocultural societies that had no concept of individual rights, in which women and children were subject to the authority of husbands and fathers, and men were subject to the authority of priests and other religious officials.

When Jewish or Muslim conservatives assert that restrictions on their freedom (really, their power) to circumcise their children infringes their freedom of religion, they are appealing to principles that also give rights to their children as autonomous individuals, including the right to bodily integrity and their own freedom of religion. Circumcision as a cultural practice belongs to collectivist societies in which the individual is subject to the group and all rights are group rights. The Enlightenment transferred these rights to individuals and gave them autonomy against not only the state, but also the religious and community officials that had traditionally policed personal behaviour.

To claim rights for oneself in order to deny them to others – even when those others are one’s own children – violates the spirit of the same Enlightenment that accorded freedom of religion in the first place.

The current debate about the propriety of religiously-motivated circumcision is essentially a continuation of the question that faced Jewish people in Europe in the nineteenth century, when secular modernity gave them religious toleration and the rights of citizens. The same question is now facing Muslim immigrants to western countries. The few who accepted the logic of the new situation argued that circumcision should be abandoned along with many of the other onerous observances that set the Jews apart as the Chosen People. The conservative majority rejected this argument, and even sought to suppress discussion of the topic, insisting that circumcision was not merely non-negotiable, but even non-discussable. Among the most outspoken of the Jewish reformers was Eugen Levit, whose disillusion with circumcision was initiated by the death of his first son after the wound became infected, and he resolved that any future boys would not be circumcised. When a second son was born the local rabbi challenged his right to have the boy’s name recorded in the Jewish registry, and when he sought to enrol the boy in a Jewish school for religious instruction he was ordered to either circumcise the boy or have him baptized. Levit recounted these experiences in a scathing pamphlet, Israelite Circumcision, Elucidated from a Medical and Humane Standpoint, published in Vienna in 1874, and including some most vehement condemnation of circumcision ever written:

“Fanatical zealots, supposedly honouring God or from a sense of guilt, may punish their own bodies with fasting, waking vigils, lashing, all sorts of self-denial and mortifications; but to impose asceticism on the body of someone else, especially an innocent, defenceless child – that no one has the right to do.”

No advocate of infant or childhood circumcision has ever given an adequate reply to this moral challenge.

As I have argued elsewhere [1], people who defend the principle of unfettered parental power forget that the political theories that give parents extensive powers over their children also give the ruler absolute power over his subjects; theories that give citizens rights against the state also give children rights against their parents, and thereby limit the power of the latter. Thomas Hobbes insisted that children were subject to parents and rulers had the authority to enforce religious uniformity. It was John Locke who refuted his case for the divine right of kings, arguing that children had rights against their parents and that citizens had rights against the state.

In other words, if children lack rights (such as bodily integrity) against their parents, adults lack rights (such as religious freedom) against the state.

References

1. http://www.onlineopinion.com.au/view.asp?article=14158

A characteristically potent analysis, Dr. Darby. Thank you for your excellent contribution to this thread …

Brian, one of the intellectual giants of intactivism has graced your blog with a potent comment. Other giants include Miriam Pollack and Leonard Glick.

I had never before heard of Eugen Levit and his pamphlet.

I am in New Orleans for the weekend, to march with the Intactivist demonstration against the brutal new policy of the American Academy of Pediatrics, which encourages parents, with a wink, to circumcise their sons because on balance “the benefits outweigh the risks.” What a load of apathetic cowardice! Circumcision is a marker that the Police State carves into the boy who will become the man. It operates on too many levels to detail here, but all involve the psychological integrity & essence of a human being. No less than female circumcision, it’s a brutal assault upon the entire person, and its purpose is to manipulate & motivate the person into behaviors & attitudes that support the authoritarian state. That state of tyranny — the police state — is more than a geographical or political entity. It is a cultural, ancestral, and religious oppressor. I have no illusions that America, or others, will any time soon give up their insane assault upon the Genital Integrity of boys, for unlike girls, they are the seed of human males who were expendable in war and peace.

The fundamental obstacle to reaching the nirvana of genital integrity in the USA is simply Genesis 17, combined with the dated notion that parents enjoy near-total freedom in deciding how to rear their children. My children are not baptised Christians, because I do not believe in infant damnation, and because I believe that baptism, like circumcision, should be a free adult choice.

I agree that the primary motivation for American circumcision gradually became cowardice, but I do not agree in a hidden authoritarian agenda. I grew up in the industrial cities of the midwest. And I was astonished as a boy at the grim conformity of provincial American life. There was everywhere a haunting fear that one might be perceived as odd. My European mother — to whom I owe my foreskin — found this fear of deviance so stifling that she concluded that American political freedom was a joke. The Bill of Rights is a bit wide of the mark, if one has a boss at work who makes snarky remarks that one drives too shabby a car (my father was told this in the 1950s). My mother was urged not to teach her mother tongue to her children. Others told my mother that her religion was the mark of the loser in the USA. In the world of my parents, adults judged each other based on their club memberships. When the hippie and sex rebellion of the 1960s hit, my mother said that America richly deserved it, although she did not agree at all with its objectives.

During the past century about 100 million American baby boys were circumcised at birth because not doing so was silently believed to create a grave risk of bullying by cut boys, of sexual rejection by women, of general rejection by everyday snobs, and worst of all, of making blowjobs impossible. My 12th grade health teacher told us, in 1967, that only “hillbillies from the sticks weren’t circumcised.” My revealing that I am intact cost me 2-3 male friendships earlier in my life. When I was 31, the adult son of a surgeon told me that my being intact was one of the most disgusting things he ever heard. Welcome to the USA, the land where the ick factor rules supreme, where intact men could suffer some of the disabilities of other sexual minorities.

I end on a ray of hope. The internet has made it possible for American women to state defiantly “I have slept with both and prefer intact.” It has made it possible for American Jews to put in the public domain their refusal to circumcise their own sons. In the USA, such declarations are revolutionary acts, body blows against the smug empire of genital conformity.

It’s my predilection that when I must choose between theories to explain an apparently insane cultural practice — a phenomenon worthy of strange aliens from another planet — I favor the sublime explanation (not that it’s hidden) over the merely prosaic. I don’t say that either interpretation is correct, of course, just that to me any explanation that lacks poetry & mystery reduces life to an animal experience that isn’t properly worth philosophy or analysis. The authoritarian society may be called a police state or a propaganda state; it may even require one to pledge allegiance to symbols of cloth & paper that resemble the icons & relics of other people, yet the symbols are ours alone, not those of Others who pledge to their own symbols. When a nation of men has been wounded — maimed — in their genitals for a hundred years, and the men accept it like drones, I choose to interpret their wound as a sublime assault upon the dignity of the people, not mere incompetence or stupidity or cowardice, but the malevolent assault of an idea that would make itself eternal in human flesh.

If they can get you to harm your children, they can get you to do anything.

True for governments, doctors and religious shamen.

Great article Brian, raising many issues which I mostly support.

As mentioned in many of the comments above, there are still some points that I would like to see elaboration for.

I can increase the argument of the Rabi quoted in the article and say that his belief is his integrity. He totally and utterly believe in the ‘word of god’ (as written in the bible) and for him (as well as the other orthodox Jews) doubting the rules or deciding to un-follow some of them will be breach of integrity.

You mention at the end of your article the concept of worldview; it would interest me to hear why (in your opinion) a secular worldview is more relevant of the religious one.

Or in other words why we should choose one integrity over the other.

I think it would be helpful for this discussion to have a common experience of male circumcision. Here is a link to the highest quality view of the surgery that I’ve yet seen. It’s performed with the Gomco clamp in this video.

http://www.facebook.com/richard.carver.779/posts/160988504041855

Circumcision(Male Genital Mutilation) is fundamentally different from other kinds of bodily modifications such as body piercing or foot binding. It is directed specifically at a highly emotionally-charged sensory organ, as unique and irreplaceable as the eyes, as critical to human community and emotional connectedness as the ability to see and be seen, to speak and to hear speech, to hold and to be held. Society’s systematic oppression and trivialization of men’s rights and emotional lives is crucial to the alienation and diversion of their energy and creativity from family and community into prefabricated establishment-sanctioned masculine roles. Indeed, authoritarian cultures have a vested interest in the routine brutalization, pleasure deprivation and emotional circumcision of males for the purpose of conditioning the next generation’s “collectively autocatalytic” hierarchy of authority figures. (Emotions are inherently self-referential. They provide our primary self-perception of our own well being. What is the social/structural purpose of the systematic suppression of men’s awareness of their own well being?) The colonization and recruitment of men’s bodies and minds begins with Male Genital Mutilation(circumcision)If you want to change men, help them come to terms with their own victimization. ~ Rich Winkel

I was pleased to demonstrate against Male Genital Mutilation in San Francisco last Saturday with the Bay Area Intactivists, at the American Public Health Association 140th Annual Meeting and Exposition. Many of us will be demonstrating on one or all days of the upcoming Assn of American Medical Colleges convention. We are protesting the ongoing circumcision ritual in America, where the doctor/circumciser maims the boy’s penis, leaving the future man with just enough penile function to propagate the species. The irony is that the loss is so great that men are forced to deny it, rather than suffer remorse, outrage, sorrow. The maiming of a man’s penis is so catastrophic most men cannot face it without despair, so denial becomes their only refuge. I will not deny it. I will spit in its face! Jonathon Conte led the way with a brilliant concept in New Orleans (inspired by UK Intactivist Richard Drucker) — I will follow up this Friday & Saturday, at the Association of American Medical Colleges demonstration, with my own variation of the “MAN WITH BLOODY CROTCH.” I will not be reduced to a medical mistake of the Twentieth Century — my body bears the ancient curse of an enraged Deity, and I will fight this heathen practice to my last breath.

Protest signs can be very effective, yet in this bizarre struggle for Human Rights, many people see our signs and think, “yeah those unhappy weirdos going on about their penis again.” In fact, I’m sure most of you have heard a very common remark from men, “Too late for me!” They are so far removed from their own conscience it doesn’t occur to them that we’re trying to stop circumcision on others. The “MAN WITH BLOODY CROTCH” is at once potent and visible from a distance, an instantly recognizable symbol — more than protest — but an outrage at the indignity that men have suffered mutely for a hundred years. It is a personal testimony, not a protest as such, and I believe it’s the symbol that will prevail in our struggle against the pro-circ medical lobby.

All of you have demonstrated in one form or another, you know how lonely it is out there with only a handful of people. If you live in the San Francisco Bay area, please, we need boots & support on the ground, whatever role you take in the demonstration this week in San Francisco, your contribution will help immeasurably. There are several adjacent buildings at the Moscone Center corner @ 747 Howard Street, the AAMC convention will have large banners in the windows redirecting people to the appropriate building. I will be the “MAN WITH BLOODY CROTCH” from about 10 am to 2 pm, Friday & Saturday. (Depending on my fatigue, I’ll try to show up Sunday but not confirming it right now.) My personal sign, which you’re free to use also, will be three lines: EQUAL RIGHTS — NO CIRCUMCISION — FOR BOYS I hope to see you all there. I hope other men will also dress with bloody crotches for the Demonstration.

https://www.facebook.com/events/444715638908094/

(By the way, on Twitter I sent this message to former Oxford prof. Richard Dawkins: “When a great man lacks the courage to speak out against circumcision, he is a small man in the universe.”)

Among other comments, you said: “So what do you think I can do to get out of this bind? Can I defend this position by appealing to anything other than secular, Western, rights-based, individualistic ethics? The question of what should liberal societies be intolerant of is HUGE”

How do we solve ethically the problem of prohibiting female genital mutilation in spite of it being a part of African and Islamic cultures? How do we solve ethically the problem of prohibiting honor killings and the execution of apostates, the stoning of infidels and adulterers? Or cutting the hands of thieves?

If we are to allow circumcision of infants based on

It all comes to a single issue, which is part of the Western values: respect for the other, for his/her body and his/her well-being. We do not discuss that killing is wrong (and yet we still allow cops or soldiers to use lethal force, and courts to apply capital punishment). There are actions that cannot be tolerated, and causing pain and bodily damage to a person who did not consent and who is not a criminal opposing resistance, is simply not allowed under our society. The fact that circumcision was allowed prior to the development of our society does not have any relevance to this argument; as all the other practices that I previously mentioned were also pre-existent and yet they are not tolerated.

Steve said “That would imply to me that there is no real way to avoid secular ethics” – And indeed that is not a bad thing. Any religious ethics is going to include irrational and supernatural arguments that do not have empirical proof. As there are several and contradictory such ethics, we cannot rely on them, not in a pluralist society. If we accept arguments from a religious paradigm, we also have to accept arguments from a different religious paradigm as there is no telling which (if any) is the truth. Or we can (as we currently do) define a secular ethics with respect for individuality, which limits the harm to any single individual and guarantees the rights of each one to hold his/her own beliefs, as long as those beliefs are not imposed on anyone else nor used to damage anybody else.

Dave Frame said: “I did not choose this community in some histroically decontextualised process by selecting from a policy smorgasboard: I was born here, and this is *my* community, too (and among the ethical commitments we cherish is tolerance of minority views); (2) I can prefer this society overall without needing to buy, in toto, the dominant ethical/policy paradigms.”. Just like we don’t choose the secular society that we were born in, we don’t choose the religious group that we are born in either. We are bound to the secular society in that it defines rules for interaction that consider both my rights, and the rights of the other one. We are also bound to our religious group, but according to the rules our our secular society, only if we choose to; our secular society guarantees us the right to renounce our religious upbringing – even if our religious society does not approve of that right. So, the question of whether we chose or not a secular or religious paradigm is not as relevant. That’s where we live. The main value of the secular Western society is that it guarantees my right to do and believe as I please, as long as it guarantees the same right on my son and my daughter and my neighbor. We have little bubbles around, which determine our right to believe or do as we please, limited to the point where we respect the same rights in everybody else. It’s really the only way to have a pluralistic and individualistic society.

He also asks: “Is there a theory that can describe the circumstances under which liberalism obliges us to be intolerant?”. I would suggest that the answer is: we are intolerant of intolerance. When your actions require you to be intolerant of the other and impose on on the other, we are intolerant of those actions. Basically, it’s a law of reciprocity. We give you every right as long as you give everybody else the same rights. Your rights cannot transgress and override the rights of anybody else.

I don’t know if any of these points will help you. I hope so.

Thank you, Dreamer – I do find these points helpful in clarifying my thinking. Thank you for taking the time to contribute so thoughtfully to the discussion.

Best,

Brian

Hi Brian,

It’s quite interesting that this an Egyptian Muslim doctor presented an article questioning the evidence of the harmful effects of FGM and inviting the governments to reconsider and allow the procedure to be offered to parents who request it. He considers the ban against FGC as gender-biased and disrespectful of traditional and cultural beliefs.

I consider this to be a very direct result of the German’s government backtracking on the ruling of Cologne combined with the AAP’s new statement.

I though you would find it interesting in relation to this paper. http://f1000research.com/articles/female-genital-cutting-is-a-harmful-practice-where-is-the-evidence/

“There are actions that cannot be tolerated, and causing pain and bodily damage to a person who did not consent and who is not a criminal opposing resistance, is simply not allowed under our society. The fact that circumcision was allowed prior to the development of our society does not have any relevance to this argument; as all the other practices that I previously mentioned were also pre-existent and yet they are not tolerated.”

BRAVO, @Dreamer! The pro-circumcision medical lobby has dominated the storyline on this issue for a hundred years. Beginning with masturbation & ending (currently) with HIV/AIDS, the pro-circ medical lobby has woven a complex tale of deceit & misdirection to conceal the fact that their advocacy of forced infant circumcision is their adherence to a Biblical mandate to civilize “boys to men” in their own image. The reintroduction of circumcision in England & the United States in the 19th century was, in my opinion, a reaction against Darwin & Evolutionary theory, which shook the foundations of the Bible & its creationism. https://theconversation.edu.au/tradition-vs-individual-rights-the-current-debate-on-circumcision-10199#comments

1. Thanks, Brian Earp, for this great article.

It brought me to a short-circuit-argument which I like to share – it might be useful in some debates. It works like this:

If agents of religions claim, that the mutilation is justified because it is such an old practice, then I would like to ask, if this is the confession, that those people themselves wouldn’t accept it, if it was a young extension of their religion?

If God had told the Jews in 1910 or 1960 that they have to do it – then you would refuse to amputate parts of your sons penis?

How is it, that a tradition increases its worth by age? In normal circumstances, a tradition which doesn’t change over time is of great worth, because it survived multiple challenges. If we sit down for eating, maybe it has much benefits, so we can’t find a better position (while of course some people eat while walking, or lying, standing…). But the key point here is the challenge. If something isn’t challenged, because it is a taboo, there is no prove in being old.

Our today discussion is probably the first solid challenge to the bad habit. We had to develop individual rights before doing so, we had to respect the rights of children, first. We had to recognize, that the idea, that children don’t feel so much pain, is probably false. That children aren’t the belongings of their parents.

And the answer is in the sentimental defense, that the claim is so old. So old, and fraudulent though? Today, it couldn’t evolve?

2. A different question:

You cite Eugene Levit from Vienna in 1874. Can you tell me, what publication that cite origins from? Is it by chance in German language in original? If so, do you have access to it?

Thank you.

3. At my homepage you find some caricatures. They are free to use for non commercial purpose if you link to the source.

Comments are closed.