By Kei Hiruta

By Kei Hiruta

Political activists are laughing everywhere. They mock the powerful and ridicule the corrupt, whether the target is a Middle Eastern dictator, a North American CEO, or a recently deceased British Prime Minister. On the streets we see the comical and the absurd in service of a demand for greater transparency and accountability. Online we see an endless flow of memes and Youtube videos to mount a further attack on the crumbling legitimacy of strongmen. Of course, not everyone is fortunate enough to dispose of arsenal to negotiate with power. Physical force still has a legitimate role to play, and it is unfortunately abused and misused in many parts of the world. But a large number of contemporary activists are giving up violent means. They certainly do not embrace their parents’ and grandparents’ weapons and tactics: Molotov cocktails, the barricades and Mao’s Little Red Book. They instead use toys, French baguettes, fake moustaches and other such items, assisted by Smartphones and MacBooks, twittering and facebooking news from the ground force.

How should we understand all this? A recent Foreign Policy article (and a TED Talk by one of the co-authors, Srdja Popovic) suggests an interesting answer. What we are witnessing, the article argues, is the rise of ‘laughtivism’: ‘a global shift in protest tactics away from anger, resentment, and rage towards a new, more incisive form of activism rooted in fun’. Of course, ‘[s]atire and jokes have been used for centuries to speak truth to power’, but their contemporary incarnations are different in that they ‘now serve as a central part of the activist arsenal’. Laughtivism, the article continues, is particularly effective in tyrannical societies where the stability of the regime depends on the culture of fear. Laughter creates cracks in the seamless whole of tyranny, and it is here that seeds for change are sown to bear fruits. Here, then, is the revised Foucauldian maxim for twenty first-century activism: where power is wedded to fear, laughter is the prime form of resistance.

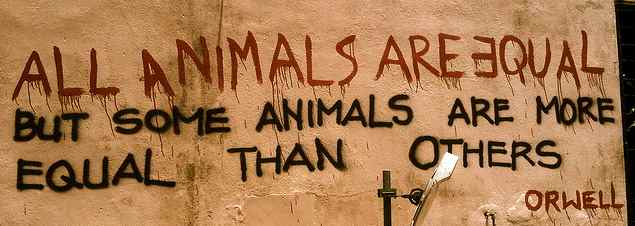

There is much to be said for this analysis, and I by no means wish to underrate the creative energy and transformative force of political laughter. Yet the Foreign Policy article, like many others (e.g. here and here), seems to overstate the case for laughtivism. First, it is not true that laughter is always or even normally on the side of the people. There is democratic laughter and there is dictatorial laughter. Satire and jokes can be used ‘to speak truth to power’, but they can also be used to conceal truth and reinforce cynicism. George Orwell encapsulates this in the unforgettable revised commandment in Animal Farm: ‘All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others.’ Dictators know how to smirk, though one may wish they only knew how to growl.

Second, there is the laughter of cruelty as well as humane laughter. Even the worst kind of authoritarianism does not consist solely of cold-blooded ideologues, capable of stabbing an enemy without showing any sign of emotion. It also hires state-sponsored sadists and criminal elements, who enjoy using their license to kill, rape and otherwise inflict pain on the powerless. But let us not demonise authoritarians to feel proud of ourselves. Remember Abu Ghraib; the laughter of cruelty is also heard in liberal democratic torture chambers. Freely elected governments too have issued permits for sadist entertainment. Laughter can serve inhumanity and no particular form of government has a monopoly of that wretched commodity.

These points should not be overlooked, but something else – something more urgent, perhaps – goes missing if we are too impressed by the power of laughtivism. It is that laughter alone cannot achieve what political activism, as distinct from mere vandalism, must ultimately aim at: a new, improved political order. Mockery, jokes and satire are powerful tools to destabilise the existing order, but they are ill-suited to the different tasks of ending chaos, filling a power vacuum and installing a new order. Laughter as a political weapon is like bullets and explosives in this respect; it must be put in storage when the task of re-building a broken community gets started. Once strongmen depart or make sufficient concessions, laughtivists must stop laughing and start deliberating and negotiating with their former enemies; they must turn their righteous anger into an enduring sense of justice; and they must realise that the destructive force of laughter could turn against itself to block the way forward.

Fortunately, fear and laughter do not exhaust our emotional options. Fear can end laughter, but so can a smile. Politics will liberate itself from both fear and laughter when laughtivists start smiling to get onto the mundane business of governance. Only then will the excitement of revolt give way to the happiness to live in a better society.

Photo credit: inju [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0]

Hola! I’ve been reading your web site for a long time now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Houston Tx! Just wanted to tell you keep up the great job!

Comments are closed.