Darlei Dall’Agnol

The British Parliament has, recently, passed Act 1990 making possible what is, misleadingly, called “three parents babies,” which will become law in October 2015. Thus, the UK is the first country to allow the transfer of genetic material from an embryo or an egg that has defects in the mitochondrial DNA to generate a healthy baby. As it is perhaps known, a defect in the mitochondrial DNA causes several genetic disorders such as heart and liver failure, blindness, hearing loss, etc. Babies free from these genetic problems are expected to be born next year. This is good news and shows how science and technology can really work for human benefit.

This procedure raised several concerns, but also revealed confusion and misunderstandings in public debates. There was the fear of opening the way to Nazi practices considered intrinsically immoral. This is certainly not the case since the prevention of mitochondrial defects does not, strictly speaking, involves any gene editing, which is a different kind of genetic engineering.[1] Now, embryo editing, which will be illustrated soon, does divide scientists and ethicists and needs further public debate. I will here present some real ethical concerns relating to embryo editing and to comment on the recent call, published by Nature, for a moratorium on the germline experiments.

To start with, let me ask: is mitochondrial DNA transfer a kind of eugenic procedure? Well, in the literal sense “Yes” (good genes), but it represents only what some bioethicists call “negative” or “curative eugenics” not positive enhancement. Now, leaving slippery-slope concerns aside for a moment, there is consensus among ethicists that negative eugenics is permissible and even morally required by the prima facie bioethical principle of non-maleficence, namely harm must be prevented. Both bioethicists working on deontological frameworks or consequentialist ones agree that curative enhancement is not unethical.[2] Thus, I hope other countries including Brazil where genetic engineering in human reproductive cells is currently prohibited (Biosefety Law – 2005) will follow the UK’s example and change the law bringing to an end the suffering of families affected by mitochondrial DNA defects. Respecting parent’s choices is also an important prima face bioethical principle. The required techniques can be made universally available through public health systems such as SUS and NHS, so questions of justice do not arise at this point.

There are, however, concerns that this kind of technology opens the path to positive eugenics. These worries may be well grounded considering the tragedies of past eugenic policies and practices and must be taken seriously. For example, writing in the prestigious journal Nature, a group of scientists has recently called for a moratorium on embryo editing since genome changes pass to future generations. One reason was this: “Such research could be exploited for non-therapeutic modifications” (italics added).[3] This statement cannot be underestimated. Gene editing may not only aim at replacing faulty genes in fertilized eggs, but the main concern is that it can be used for non-curative purposes leading, for instance, to designed superbabies. Now, in the case of nontherapeutic enhancement, there is no ethical consensus among scientists and philosophers. Embryo editing divides scientists and they don’t know why. Philosophers are in no better position: deontologists (e.g., ethicists working on rights-based theories) normally reject positive eugenics; consequentialists (e.g., ethicists arguing for the maximization of happiness) support nontherapeutic enhancement. Therefore, we do need more conversation.

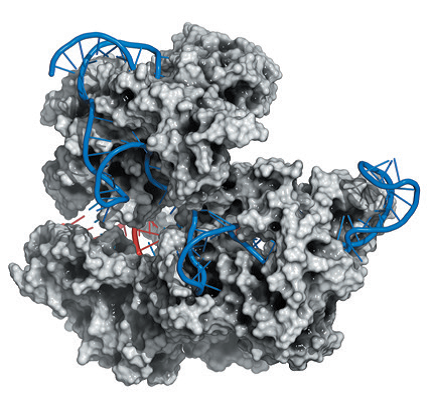

To avoid further misunderstandings, it is necessary to stress that gene editing can be applied both in somatic or in germ (sperm and eggs) cells. A recent development of a technique, known as CRISPR/Cas9 seems simple to apply and efficient for editing genes purposes. An illustration may perhaps help to understand it:[4]

CRISPR uses an enzyme (white) and RNA guides (blue) to cut DNA at a point specified by a DNA fragment (red) making targeted gene edits.

Applied to somatic cells, this procedure does not raise ethical problems and may also lead to great benefits, for instance, the cure of HIV/AIDS, haemophilia, anaemia, cancer etc. Thus, gene editing can have clear therapeutic uses. Here deontologists and consequentialists ethicists would agree too. But this kind of technique has the potential of leading to positive enhancements if applied to germ cells, that is, it may produce change in the basic genetic features of future babies such as increasing physical and cognitive abilities and that is why scientists are calling for a moratorium and more public debate. This is really needed not only for efficacy reasons (scientists still do not know how to guarantee the nucleases do not make mutations in untargeted locations), but also for ethical ones. In their post “Editing the germline – a time for reason, not emotion” Gyngell, Douglas and Savulescu argued that “beyond safety, no good reasons for restricting germline editing research have been identified.”[5] I believe, however, that we need more than risk/benefit analysis of the procedure itself taking into consideration also other prima facie bioethical principles such as justice.

As a philosopher, then, I welcome the call for more public debate. I believe that since we do not have consensus among deontological, consequentialist and virtue ethicists, we should right now support germline editing if and only if the technique is safe, but, most importantly, for curative or negative eugenics only. Here, one can leave slippery-slope concerns aside since it is possible to elaborate a public list establishing all diseases prevented, for instance, cancer, Huntington Disease, forms of Alzheimer etc. As philosophers, we must remind ourselves that ethics is also progressing and only recently have we started to discuss ways of overcoming dichotomies in ethical theory such as mentioned above. We are far from having a commonly sharable morality.

Perhaps the call for a moratorium came, unfortunately, too late, since only a few countries ban germline research or genetic engineering and the rumours in the scientific communities of the first studies, which are about to be published, is a sign that we may have crossed the therapeutic/nontherapeutic line. In this sense, I would recommend the enforcement worldwide of the principles of the UN’s Declarations (Bioethics, Human Genetic Data etc.) instead of unilateral moratoria. It came, certainly, too late for the non-human animals since countries such as China are already producing monkeys with customized mutations. I believe this is wrong since these transgenic animals may just be used as labs’ tools.

To support the call for more debate, I would like to raise some questions related to prima facie principles of justice: how can we guarantee that society will be fairer if we allow for more than therapeutic germline editing leading to “edited” and “non-edited persons”?; are we willing to see private corporations owning particular editions of human genome (superbody 2.3, superbrain 5.9 etc.) or should positive enhancements be freely available to everyone?; can we really presume that these future edited-persons will not have their emotive well-being affected once they find out that they were edited?; would they feel responsible for the kind of person they are or the way they behave? Since we do not yet have clear answers to these questions, I think that the ethics of germline edition at the embryonic state should be a negative one for now, that is, restricted to the principle of non-maleficence which justifies therapeutic uses only.

[1] Mitochondrial DNA diseases are avoidable using two techniques: pronuclear transfer (PTN) and maternal spindle transfer (MST). For an illustration of these techniques see: CRAVEN, L. et all., Pronuclear transfer in human embryos to prevent transmission of mitochondrial DNA disease. Nature, V. 465, 2010, pp. 82-85.

[2] I argued for this point in “Respect for Persons: Rawls’ Kantian Principles and Genetic Policies”. See: Dall’Agnol, D. & Tonetto, M. (eds). Morality and Life. Pisa, ETS, 2015. pp.127-145.

[3]Lanphiers, E. et al. Nature, vol.519, 26 Mach 2015, pp. 41.

[4] Nature, 519, 12 Mach 2015. (MOLEKUUL/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY)

[5] https://blog.practicalethics.ox.ac.uk/2015/03/editing-the-germline-a-time-for-reason-not-emotion/

I would like to thank CAPES, a Brazilian federal agency, for supporting my research at the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics.

Fantastisc issue Darlei. I have comments, but, for now, I’d like only to point out something I found ambivalent in your approach. Let me quote you. You said: “I believe that since we do not have consensus among deontological, conseqFantastisc issue Darlei. I have comments, but, for now, I’d like only to point out something I found ambivalent in your approach. Let me quote you. You said: “I believe that since we do not have consensus among deontological, consequentialist and virtue ethicists, we should right now support germline editing if and only if the technique is safe, but, most importantly, for curative or negative eugenics only.” First, why consensus between philosophers should be taken as a reason for fostering or precluding a policy? And, second, why IF AND ONLY IF it is safe BUT FOR NEGATIVE OR THERAPEUTICS EUGENICS ONLY? This seems to be ambigous. The iff-clause seems to be supporting just the same as Gyngell, Douglas and Savulescu; nevertheless, what it seems to be claimed after is just the opposite.

Thanks, Marco, for your challenging comments. They give me the opportunity to clarify further my views. First, if you find ambiguous the sentence, let me put it in a more straightforward way. I was trying to sort out two necessary and sufficient conditions to carry on embryonic editing, namely: iff it is safe and for therapeutic purposes only. This is the main spirit of the call for a moratorium in my view: do no cross this red line now. Perhaps, in a near future, we could establish in a fairer way the non-therapeutic uses. To reach this stage, we have to do our homework and to discuss what constitutes a just society, that is, one that uses genetic engineering without creating new forms of discrimination based on biology. Second, I welcome the call for more public debate, including among philosophers and ethicists, not only for reasons based on justice. I was using middle level principles to justify the above view, which is compatible with most ethical theories. But, as you know well, we have many disagreements in normative ethics. The good thing of a call for more debate is, for us philosophers, to have the opportunity to discuss whether proposals such as Parfit’s triple theory can, in fact, give us a promising way for assessing non-therapeutic uses of embryonic editing. As you know, Parfit holds that “an act is wrong just when such acts are disallowed by the principles that are optimific, uniquely universally willable, and not reasonably rejectable”. I would like to add “by a virtuous person” to try to make compatible not only deontology and consequentialism, but also some varieties of virtue ethics reaching, in this way, a real triple theory. I believe we need to discuss further this purpose. In fact, we could start by testing it asking what such superprinciple would require regarding the non-therapeutic uses of embryo editing. So, what you think?

Darlei, you say that “in a near future, we could establish in a fairer way the non-therapeutic uses”. And you say “perhaps”, for you think a condition is that we have “to do our homework and to discuss what constitutes a just society, that is, one that uses genetic engineering without creating new forms of discrimination based on biology”.

But this would be insane! Philosophical homework on what constitutes a just society is an endless task. I think the issue at bottom is on the value of the so-called precautionary principle. The call for a moratorium is, or so it seems, related to a widespread fear that unrestrained uses of technics of embryo editing will produce bad consequences (inequality in power would be one of them). But how likely is this bad outcome? We cannot stipulate that, but this is the very point of the precautionary principle: the burden of proof lies with the proponents of non-therapeutic uses since the worst cannot be ruled out. But this version of the precautionary principle is unreasonable! After all, the principle can be reasonably rejected. It cannot be reasonably accepted as an universal rule to restrain scientific reasearch if we already have good evidences that researches and technologies are safe.

So, I’m not convinced. I agree with Gyngell, Douglas and Savulescu that no good reasons for restricting germline editing research have been identified, except safety. In my opinion, for ruling out a practice,there should be reasonable evidence that in licencing it we are promoting violations to people’s rights (or that severe unjust inequalities will abound).

I think, Marco, that it is a very poor “argument” to say that to discuss what constitutes a just society is an endless task. I can’t believe you think that philosophers discussing genetics and justice are just wasting their time.

I am not against non-therapeutic uses of gene editing, I just wanted more discussion and it seems too late as you can see here:

http://www.scmp.com/tech/science-research/article/1774254/chinese-scientists-successfully-edit-human-genome-first-time

I have political-philosophical concerns also since this was done in a single-party state, but I suspect you are not willing to discuss them.

Comments are closed.