by Joao Fabiano

Why inequality matters

Philosophers who argue that we should care about inequality often have some variation of a prioritarian view. For them, well-being matters more for those who are worse off, and we should prioritise improving their lives over the lives of others. Several others believe we should care about inequality because it is inherently bad that one person is worse off than another through no fault of her own – some add the requirement both persons should be equally deserving. Either way, few philosophers would argue that we should worsen the better off, or worsen the average, while keeping the worse off just as badly off, only to narrow the inequality gap. Hence, when it comes to economic inequality we should prefer to make the poor better off by making everyone richer instead of making everyone, on average or sum, poorer. Moreover, in most views it is reasonable to care more about inequality at the bottom and less about inequality at the top. We should prefer to reduce inequality by making the worse off richer instead of closing the gap between those who are already better off. I believe a closer inspection at how these equalitarian/prioritarian preferences translate into economic concerns can lead one to reject a few common assumptions.

It is often assumed that the liberal economic model, when compared to strong welfare models, is detrimental to human economic equality. Reducing poverty, equalitarianism and wealth redistribution are, after all, one of the chief principles of the welfare State. The widening of the gap between the top and the bottom is often cited as a concern in liberal States. I wish to argue that out of the various inequality statistics available, if we look at the ones that seem to be more relevant for equalitarian ethics, then strong welfare States fare worse than economically liberal States[1]. For that, I will focus on a comparison between the US and European welfare States’ levels of inequality.

Domestic inequality

It is true that under simple measures such as the Gini coefficient inequality in the US is wider and has been rising. But if we reject any form of extreme equalitarianism that prescribes making everyone worse off in order to narrow the gap, then a closer look at the US economy seems to reveal that it has led to a better distribution of wealth overall – a picture that simple measures miss.

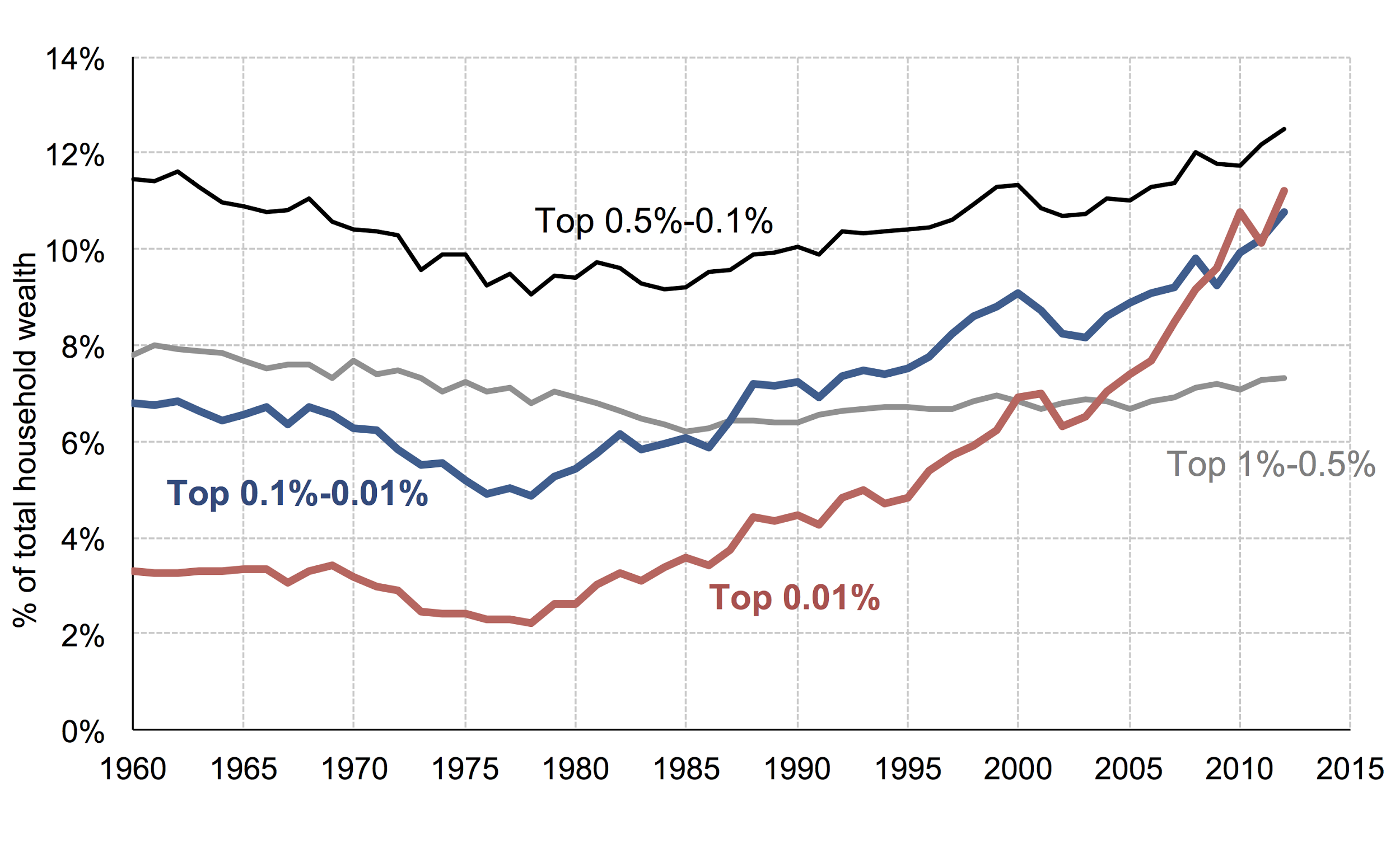

A big part of the increase in the American wealth inequality was at the very top, among the households above the 99.9th percentile[2] whose net worth surpassed 20 million dollars in 2012 (Figure 1). But why should we care whether Warren Buffett now has 50 billion dollars rather than 20 billion dollars more than George Soros? Whether Oprah now can afford two more private Islands than Madonna? This gap is largely irrelevant and even comic to consider. The lives of millionaires and billionaires are not significantly more unfair because their wealth now differs by some dozens or hundreds of millions, let alone are our lives worst because of it. If a billionaire gets another billion, the Gini coefficient will indicate a greater increase in inequality than if several families go from poverty to extreme poverty; its capacity to track morally significant inequality is limited.

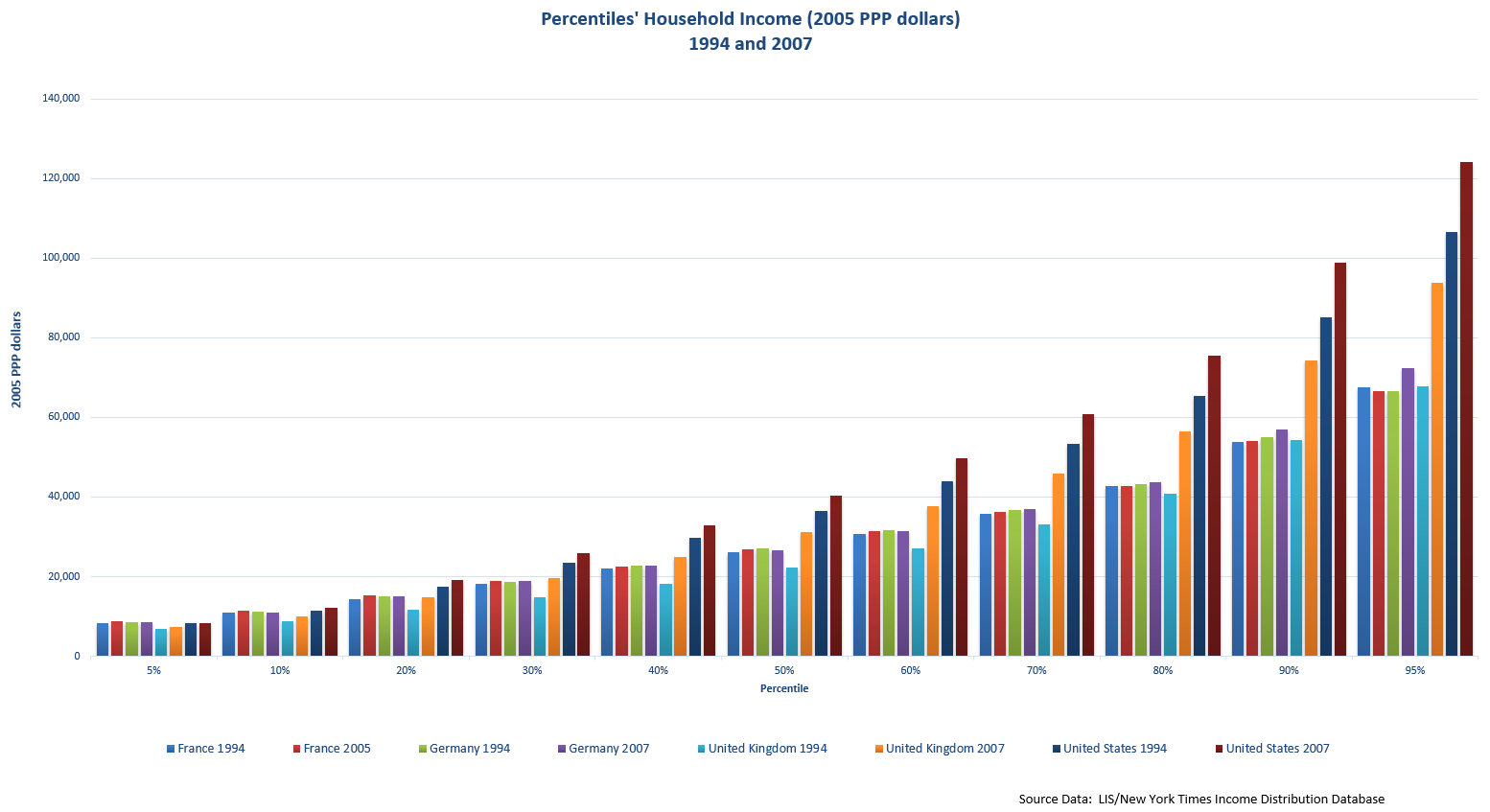

While the 5th percentile of real disposable household income distribution[3] has been almost identical from 1994 to 2007 in the US, the UK, Germany and France, all other percentiles have seen their income increase more in the US than in any of the other countries we are looking at (Figure 2)[4]. This suggest the change in US inequality is a product of the US rich being richer than before (and being richer than the rich in Welfare States) and the poorer remaining mostly the same as before (and about the same as the poor in Welfare States). Average income increased, total income increased, everyone but the bottom 5% got richer and the bottom 5% remained the same – all of which is compatible with the Gini coefficient and other simplistic measures of inequality increasing[5]. These changes do not look like a worse outcome in comparison with Welfare States. It’s also worth noting that from 1994 to 2007 the US bottom 5th is not comprised of the same households, who are constantly being replaced by poor immigrants and younger households at a much higher rate than in Europe. Nearly 58% of US households in the bottom 20% in 1996 moved to a richer group by 2005.

The vast majority of a country’s population is not at the very bottom. Other than the 5th percentile in Welfare States often being equally well off and sometimes slightly better off, every other percentile earns more in the US than in the UK, Germany or France. Several of them earn significantly more. The vast majority of Americans are, and have become, significantly wealthier than the vast majority of citizens of Welfare States[6].

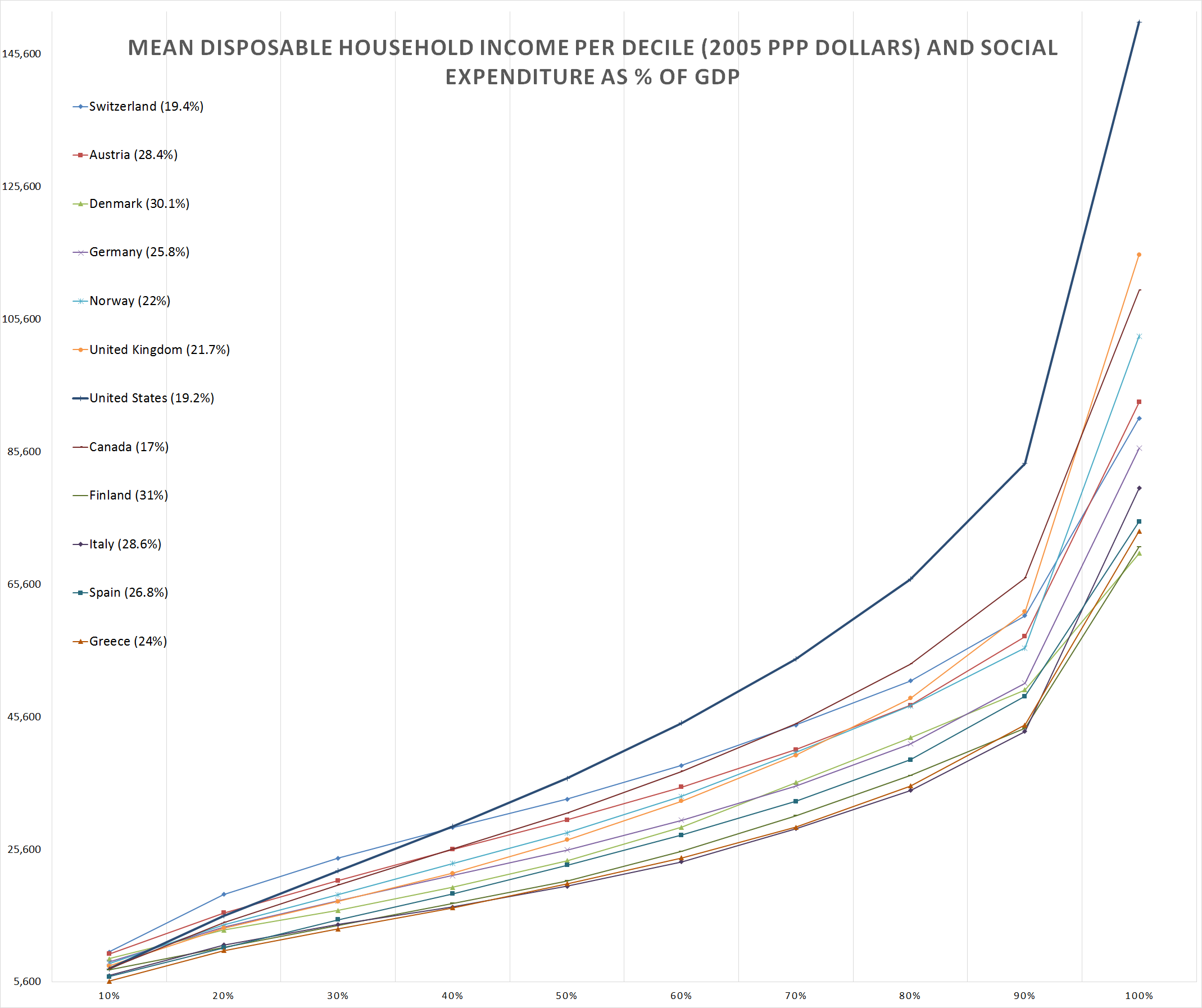

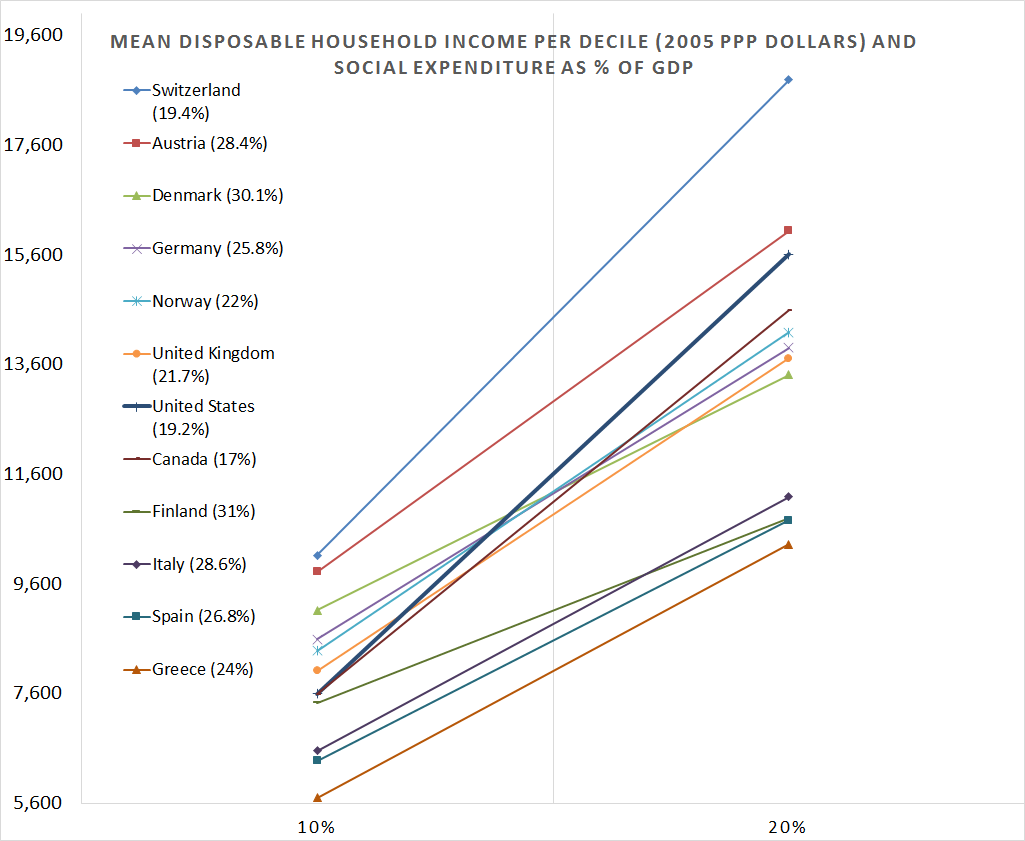

If we look at the average disposable household income in 2004 (Figure 3 & 4), the US lowest decile[7] is wealthier than the lowest decile of many Welfare States, and any other decile is wealthier in the US than in any other European country, with the exception of Switzerland and Austria. For instance, other than having the lowest decile slightly worse off, there is no US income decile poorer than their respective Danish decile. Denmark spends 30.1% of its GDP on welfare; the US, 19.2%. So much for the Danish model. Many countries that fare well in this graphic have similarly low social expenditure (e.g. Canada and Switzerland). It seems, then, that extreme equality could have come at the cost of leaving everyone, including the poor, worse off; or, sometimes, at the cost of leaving the poor the same and everyone else poorer than they could have been.

It should be remembered that unless one only cares about equality, increases in inequality could be outweighed by higher total and average wealth. Let’s look at those figures. In the last year alone, the US generated more wealth than France has managed to accumulate over its entire history, 17.4 versus 15.3 trillion dollars. In 1988, the US inflation-adjusted GDP per capita was the same as the current German figure; after 1988 there was not a single year where Germany had average wealth higher than the US. There is only one US state with lower GDP per capita than the UK; or none if we make interstate PPP adjustments. Equality by leaving everyone worse off than they could have been, either in total or on average, does not seem to be prescribed by recent versions of equalitarian ethics.

The recent Salon article “35 soul-crushing facts about American income inequality” brings the following analogy:

“Imagine 10 people in a bar. When Bill Gates walks in, the average wealth in the bar increases unbelievably, but that number doesn’t make the other 10 people in the bar richer. “

I believe this is, in fact, a somewhat accurate picture of US inequality, as far as two-line analogies go. But it is no soul-crushing fact. Does a bar suddenly become worse because Bill Gates walked in? The other 10 people did not get poorer. In real-life America, most of them actually got richer.

Arguably, all of the numbers above are the result of the US’s astonishing capacity for producing wealth, fuelled by a free-market, low tax economy. But these facts are merely about domestic wealth and domestic inequality. How does the liberal model impact wealth distribution worldwide?

World inequality

Each year the US absorbs almost half a million immigrants from developing countries. For over a century, immigration has been seen as one of the defining forces behind the American economy and American identity. In 2013, the US had 35 million immigrants from developing countries, 85% of the total 41.3 million immigrants and 11% of the total US population [8]. Mexico is the biggest source, responsible for 11.5 million immigrants (28%), but is also one of the richest developing countries. Nonetheless, in 2010 its average disposable household income was $14,783, similar to US 2010 second decile ($14,979). Moreover, the Mexican third decile average was $5,815; if after migration they became the US poorest 10%, their disposable income would still increase substantially to the figure of $7,108. South Asia is responsible for 8.3 million of the US immigrant population (20%). India, a representative and the biggest South Asian source of immigrants, had a 2007 average disposable per capita income of $1,927, a third lower than 2007 US poorest 10% ($2,871)[9]. With such high level of immigration from developing countries, even if the bottom deciles of households in the US were getting poorer (which they are not), given that a significant share of these households are constantly being replaced with immigrants originally much poorer than US poorest, the impact of the US on global inequality could still be positive.

From 2010 to 2013, the US took in more immigrants from developing countries than the total amount of Syrian refugees currently attempting to enter the EU. This is the worst immigration crisis of the last 60 years in one case and business as usual in the other. But comparing US and European immigration data is hard. I could not find one unified detailed dataset for the EU. I will focus on some UK statistics for comparison, which has overall figures similar to the EU average. Although the UK has an similar foreign-born percentage to the US (11% UK, 13% US), there are relevant striking differences in their immigration profiles. One third of UK foreign-born residents come from inside the EU, which has only two, small, developing countries[10]. From the other two-thirds composed of non-EU foreigners, approximately 24% who were granted a visa in the year ending on March-2015 came from developed countries, suggesting that half of UK immigrants are from developed countries. The UK’s Office for National Statistics estimate for 2013 indicates 56% of the foreign-born are from the developing world and 44% from the developed world. In comparison, only 15% of US immigrants come from developed countries. Furthermore, even the immigrants who do come from developing countries are normally selected based either on high income, education or skill – which presumably causes an increase in global inequality. Moreover, immigrants are seldom allowed to settle (139,739 in 2013 in the UK, compared to 990,553 in the US), second-generation immigrants do not automatically earn citizenship, and illegal immigrants are rare (8% compared to US 25%). Permanent, low-income, low-skill immigrants from developing countries form the majority of US immigrants, and are likely to be a very small percentage of UK immigrants. Currently, there seems to be no feasible legal bureaucratic path that could lead a low-skill worker’s family from a non-EU developing country to gain a permanent residency status.

This discrepancy between the US and the UK immigration policies is not unreasonable. If the EU were to have the same immigration profile as the US, then social expenditures would increase by a greater factor than government revenues[11]. The more the State attempts to redistribute wealth through redistributionist taxation, the more the poor will cost the State, and the less the State will be willing (or even prepared) to take in poor immigrants. So far as social security is concerned, being a EU citizen (or immigrant) confers many more advantages than being a US citizen (or immigrant). A UK immigrant has better access to free health care than a US citizen, and possibly better access to free higher education in much of continental Europe. It is no surprise then that one is more willing to receive the world’s poor than the other. But this is precisely the definition of elitism. When belonging to a smaller selected group has far more advantages than belonging to a larger inclusive one, we will normally say the former is elitist and contributes more to overall inequality than the latter.

Conclusion

I have presented data that suggest that strong Welfare States have lower income growth, no less domestic inequality and lower immigration of the poor than one economically liberal State, the US. I have proposed a few plausible mechanisms whereby a stronger welfare State could be cause of these worse results. High social security arguably disincentives poor immigration, and high taxation arguably leads to less income growth, and no less domestic inequality – both of these defining features of welfare model. Domestic equality, total wealth, average wealth, and world equality all seem to be better promoted by liberal capitalism. At the very least, any defence of strong Welfare States on the basis of equality will have to deal with the numbers I have presented here and their proper interpretation in light of equalitarian/prioritarian moral views.

Here is a slightly more accurate version of Salon article’s analogy:

“Imagine 10 people in a bar. Bill Gates walks in, 8 people get richer and the bar takes in one poor passer-by and gives him a job.”

Is not this the kind of bar we want?

Endnotes

[1] I will not argue for any political orientation/party, nor that countries should adopt certain policies, nor that under most or many statistics there is more equality in liberal States. I will argue there is lower inequality of the kind modern equalitarian/prioritarian ethics cares about. I will concentrate on wealth inequality per se, because wealth redistribution is one of the principles of the Welfare State. If we are concerned with well-being inequality, given that income produces diminishing returns on life satisfaction, inequality of the natural logarithm of income would be a better measure. But this inequality is drastically lower than wealth inequality, not a main concern in itself and not the focus of this post.

[2] 99.9th percentile in the wealth distribution is the cutoff wealth that makes a household better off than 99.9% of the given population.

[3] The 5th percentile of the household income distribution is the income such that the household is better off than 5% of the population, i.e., the bottom 5%. Disposable household income is the income from wages, self-employment, and capital, plus social transfers, minus direct taxes paid. Real disposable household income is the disposable household income adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) and inflation in 2005 dollars. Unless stated otherwise, all measures are in 2005 dollars and adjusted by purchasing power parity (PPP). This is crucial for any inequality comparison between different times and countries. An even better adjustment would have to give more weight to purchasing parity of essential goods, which are generally much cheaper in the US.

[4] The complete dataset on income inequality from the LIS/New York Times Income Distribution Database can be found here. I have selected the data on household income in France, Germany, the UK and the US in 1994 and 2004. I have started from 1994 because this is the period where it is commonly said that US inequality skyrocketed and because before 1994 the years did not all match. I have ended with 2004 because the last Great Recession hit countries asynchronously, and there were no data for after the Great Recession. Two years after 1994, the US approved one of the most significant liberalist piece of legislation of its recent history, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act. This was also the period where US immigrant population increased dramatically. Unfortunately, my 1994 start leaves out France’s significant increase in the 5th percentile household income from 1978 ($5288) to 1994 ($8,366) which was not matched by the US ($8,125 to $8,381). This might be explained by the change in French immigration policies during the 70s.

[5] Interestingly, most of the alarming recent statistics on US inequality come from the same LSI dataset I have used here. It is not that these other measures are wrong, inexact, manipulated or are less economically relevant than the ones I have presented here. But they miss morally significant aspects of the overall evolution of the distribution of wealth.

[6] Perhaps the comparison gets trickier in this case. World A has 900 citizens with perfect equality, plus 50 rich citizens and 50 poor citizens. World B has 1000 citizens with high inequality, but the 50 at the bottom – and only them – are slightly better off than the 50 at the bottom of World A. In this case, unless one has an extreme prioritarian view where only the well-being of the bottom 50 matters, it seems to me World A has less inequality. The total number of citizens affected by inequality seem to matter.

[7] A decile is 10% of the population. The lowest decile are the 10% poorest, the highest decile are the wealthiest 10%. The mean income for the lowest decile is the mean income of the 10% poorest. I have used 2004 because it is the only pre crisis year with data for all major European country.

[8] I have used the UN criteria, i.e., all countries with HDI below 0.8 are developing countries.

[9] I have used per capita disposable income for India because it has the third largest average household size, making average household disposable income misleading. I have estimated the US poorest 5% figure by using its mean household income divided by average household size.

[10] Bulgaria and Romania are the only two developing countries in the EU according to UN criteria. Bulgaria per capita disposable income in 2013 was $8,921.

[11] Average income in developing countries is less than a half of the income tax lower threshold at most European welfare States. Even if average-income immigrants see their income double upon migration, they would still pay no income tax.

Much of this argument rests on the assumption that welfare states are redistributionist. Joao Fabiano gives no evidence for this, but simply states:

Now this is simply not true for the European welfare states, neither historically as to their 20th-century origins, nor in terms of how they actually work. The underclass benefits least, and that would be more true if we included education expenditure as typical ‘welfare-state’ expenditure. Now that does not in itself make the welfare state a ‘failure’, but it is evidence that politicians lied about its purpose. In fact, it works quite well for the middle-class voters, who successfully extracted funds from the state, by using their advantages in the political process. The underclass does not have the political weight to force redistributionist policies, so in general there are none.

I once suggested an alternative for so-called equality policies, which would address the plight of the underclass: equality of suffering. It is formulated as a clause in a constitution:

That is certainly prioritarian. However, it deliberately ignores income and wealth, because that’s not what matters if you are at the bottom of the pile. Joao Fabiano rightly points out that it does not matter to the poor, if the rich have one gold-plated bath, or two, or three. However, he draws the wrong conclusion that marginal increases in income do matter to the poor. If you look at the real conditions of life for the underclass, earning $1.10 per hour is in fact little better than earning $1 per hour. That would be as true in Europe as in the United States.

Looked at in this way, the claims made for the US, namely that it shows small increases in the lowest incomes over time, would be irrelevant to the political issues raised.

What we can say is that liberal societies are characterised by huge inequalities in income, wealth, health, and well-being, and extreme suffering for the most disadvantaged groups. An illiberal society is clearly preferable on those grounds alone. Comparing liberal with liberal – EU member states with the United States – will not serve to ‘disprove’ that, even in the way that Joao Fabiano intends. The European welfare states are not illiberal, and the welfare state is not in itself illiberal. Nor is it redistributionist, nor is it egalitarian. The income statistics that Joao Fabiano cites don’t do anything to back up the political claim he makes, namely the superiority, or at least superior functioning, of liberal societies.

I was evaluating the welfare State according to its declared principles, and redistribution is one of them. I agree that historically the welfare State (and even modern democracy) was a middle-class enterprise never meant to leave the poor better off; its declared principles are hypocritical. I haven’t seen data on it, but I suspect most of the “We are the 99%” movement is composed by the 10% upper middle class and to further their interests. However, I see my post and this hypocrisy as two bodies of facts pointing in the same direction rather than being incompatible.

I didn’t say going from $1/hour to $1.1/hour is a substantial improvement. I believe I might have implied the minor differences in the bottom 5% income between countries aren’t very significant.

My post wasn’t meant to argue about the extreme liberal or illiberal societies. Regarding economic models and taxations, the US is more liberal than the EU, and their poor are equally poor and their rich much richer. I haven’t extrapolated any conclusions about the extremes of this spectrum. But it is clear that if I were to extrapolate, it would indicate illiberal societies should not be preferable, given that slightly more liberal ones fair better. The fact this extrapolation would be uncertain does not mean, at all, that illiberal societies are clearly preferable.

Liberal societies don’t ‘fare better’. There are thousands of posts and comments online, which make that claim over and over again. Like this … “Here is a liberal society in liberal state x and there is a non-liberal society in non-liberal state y. X has a higher GDP per capita therefore liberalism is better.” Americans would speak of free market or capitalism, since ‘liberalism’ means something different to them, but the message is always the same: our system makes us richer, therefore it is better.

There has to be a point when you stop taking this seriously as an argument. Obviously, these people believe it themselves, often in a very self-righteous fashion. The tone is however so similar, to the tone in which other right-wing credo’s are propagated, that it seems a question of style rather than substance. Immigrants cost us money, the EU is destroying our nation, Islam is conquering Europe by stealth, climate change is a fraud, and so on: those who hold these views are utterly convinced that they are right. I suspect that there are biological origins to this phenomenon, perhaps a specific right-wing personality type, which is immune to doubt.

In any case there is no point in arguing about the issue, when there are so obviously no shared premises. If someone is convinced that economic measures such as GDP per capita tell us which society is morally preferable, then what point is there in telling them that it is not true?

The real challenge is to recognise the impossibility of argument, and the consequent impossibility of political process, and to move on from there. The population is divided on such issues, as they are on many others, and clearly one response to that is to offer a choice of outcomes, rather than the uniform policies which characterise the nation-state. Although I despise libertarianism, for instance, I am strongly in favour of a separate libertarian territory, free of government and open to all libertarians.

The population is divided on classic distributive justice themes, such as “is it better if all are poor rather than some are rich?”. The state should accommodate that plurality of values. One way to do that, is to have two states with different economic systems, a solution which was tried once in Europe. However, if we are prepared to give the problem serious thought, then surely there are other options, which allow each individual to choose the outcome which is most appropriate for their individual value orientations.

Of course that is a break from the tradition of the nation-state, which has one law, one government, and one economic policy. However, if we continue to insist that issues of distributive justice be resolved by debating them, then we will simply get endless repeats of the same incompatible positions.

To be clear, by “fare better” I meant in terms of overall income distribution alone. My analysis was limited to wealth/income distribution between EU and US and their effects on world distribution.

The article contradicts itself as to its focus. Note 1 says “I will concentrate on wealth inequality per se, because wealth redistribution is one of the principles of the Welfare State.” The article then goes on to discuss income inequality. The article does not confine itself to “wealth/income distribution between EU and US and their effects on world distribution” as the author claims. It presents some limited comparisons between a limited number of states, and then ends with sweeping claims such as “Domestic equality, total wealth, average wealth, and world equality all seem to be better promoted by liberal capitalism.”. Such claims cannot be backed up by the quoted data, even if it was all accurate and correct conclusions drawn, because it is insufficient for that purpose.

My conclusion was based on the data I have gathered – which is actually quite substantial if you compare it to most data cited in many non-academic publications and debates on this matter. I agree it is not sufficient to lead to a definitive conclusion, but it is an indication of something, which is why I said “seem to be”. Furthermore, unless there is sufficient data showing otherwise, it certainly demystifies the often cited notion that the US poor are significantly worse than the strong welfare States’ poor. For instance, the US bottom decile almost as poor as the Danish bottom decile, and every other decile is significantly richer in the US.

Let me explain why national economic statistics cannot be used to judge the merits of different types of societies. Joao Fabiano claims that: “In the last year alone, the US generated more wealth than France has managed to accumulate over its entire history, 17.4 versus 15.3 trillion dollars.” Now that is nonsense, because the cited sources refer to current national wealth estimates for France, and US annual GDP, which are non-comparable. The cited source does not provide any figure for the ‘wealth which France has accumulated over its entire history’. There is no such figure, because it can only be calculated from historical GDP estimates, which are guesswork prior to the 19th century. (The comparison also overlooks the simple fact that the US is larger than France.)

What we can say is that the US has a higher per capita GDP, than France or any other large EU member state. However, that can never be attributed solely to current economic and social policies. The emergence of the United State as a large and prosperous economy cannot be explained without historical background. It is not possible to say how far back that should go, but the present pattern of global inequality of development was already visible by 1800, with western Europe, the early US, and Japan doing much better than for instance sub-Saharan Africa. In the case of the United States, a European economic system was imported in the 17th and 18th century. Now to make valid comparisons between for instance liberal and illiberal economies, you would need economies which had been liberal / illiberal, during the entire period which is relevant for the comparison. Although you could say that the United States has been ‘typically American’ for 200 years, European states and societies have often been much less stable, with shifting regimes and ideologies.

So we also see that, for instance France is richer than Myanmar, but we cannot say that is the work of the current government and its policies. Perhaps it is the result of economic reforms under the Vichy regime, or of French colonial expansion in the 19th century, or the Christian heritage of France. We don’t know. We can see, for instance, that the United Arab Emirates is much better off then Malawi, and perhaps that is because Islam is superior to Presbyterianism. We don’t know. Only comprehensive historical comparisons could provide evidence for such claims.

For short-term comparisons, economic statistics can be effective. We can compare the effects of differing policies on economic growth, in a time frame of a few years. We can’t do that with long-term inequalities in economic development, because they are simply not responsive at that timescale. In the time scale that is relevant, it is difficult to find states and societies which remain comparable with each other over the entire period.

Simply adding up a country’s GDP over its entire history will not give you any estimate for how much wealth it has accumulated. To calculate total wealth accumulated you have to use total assets minus total liabilities. I don’t overlook the fact the US is larger than France, I was looking at total wealth as stated at the beginning of the paragraph.

OK, then my data for the US, UK, France and Germany from 1994 to 2007 must prove something. Just prior to 1994 you have Ronald Reagan in the US and his signing of the Economic Recovery Tax Act (among other things); just after 1994 Bill Clinton signs the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act. The US poor remain as poor than the other States poor, and everyone else gets much richer.

Thanks, Joao, for the interesting take on inequality. But I think you overstate your claim that the US actually fares better on inequality than the EU.

You start off by noting the Gini is too sensitive to outliers of mega wealth. Fair enough. But your response isn’t to focus on, say, inequality between lower deciles. Rather, you change the subject entirely, to income growth at the bottom/middle segments of the population. That isn’t a measure of inequality at all, as it doesn’t assess the relative state of different segments of society.

You might think that relative status is morally irrelevant, and we should just care about absolute well-being across different segments of society. Fine, but then you’ve just rejected the notion that equality matters in the first place. And you can’t argue the US is more equal than Europe without making reference to equality, an essentially relative notion.

Those were two independent points. If inequality got higher mostly because of inequality at the top 1%, then this should not be a significant concern. If inequality got higher, but the poor got richer (or as rich) than in countries where the push for equality was stronger, then this should not be a big concern. Both of them depend on the fact that (simple) equality does not matter in the first place. Instead, inequality at the bottom matters more than at the top and how rich the bottom is matters in itself; note that equality still matters here and that this is close to many views of equality in contemporary ethics. There is also the third point that average and total wealth increased more in the US, so if you care about these, there was also a substantial gain.

You are right that one should take a look at inequality at the bottom, but I could not find any detailed data on that.

Okay, thanks for clarifying – you do reject egalitarianism per se, it sounds like (according to which ‘simple’ equality does matter), so at least a significant portion of contemporary equality discourse isn’t within the scope of your argument. (I think your argument is more compatible with prioritarianism, and that’s really a theory of distributional justice, not the value of equality per se) But then, I don’t see in what sense “equality still matters” to you. You say you care about “inequality at the bottom”, but how is that defined? It’s not the same thing as growth at the bottom, as that doesn’t refer to how, well, equal different groups are. Is it actually the difference between, say, the middle class and the poor? As given you don’t have any stats on that, what evidence is there for your claim that, in terms of inequality at the bottom, liberal states are more (or at lease no less) equal than welfare states? (also, why does the difference between the middle class and the poor matter more than the difference between the rich and the poor?)

Maybe what you mean is, equality is only valuable when the means by which equality is achieved is improving the lot of the poor/middle class? And Europe has achieved greater equality by means of ‘levelling down’ the rich. That’s an interesting and compelling theory (arguably another way of cashing out the levelling down objection to egalitarianism), but again, I don’t see the evidence you’ve offered as supporting the empirical claim. You’ve compared the US and the EU, but not analyzed how the EU achieved its greater equality. It may be that welfare policies did indeed increase equality by means of improving the lot of the poor (at the expense of the rich, which is fine by egalitarian standards), and in fact the US has foregone a similar opportunity to further improve the lot of the poor through more redistributionist measures. This is compatible with slower wealth and growth in the EU overall, the result of a complex of other factors.

He did not ‘compare the US and the EU’ in any respect. All the European statistics quoted refer to individual states. No eastern European states are included either. You should not give him credit for things he did not do.

Joao Fabiano states that

He implies that this is a case of “equality by leaving everyone worse off than they could have been” which he rejects. However, the quoted statistic can not prove anything in isolation. Its accuracy is also dubious. Joao Fabiano copy-pasted it from the right-wing weekly The Spectator, where it was presented as a back-of-the-envelope calculation. In fact this is a right-wing trope which has been circulating for several years: comparing a poor US state to a European welfare state.

Comparative regional GDP estimates for the EU and the US are difficult to compile, and so far as I know no such study has been done yet. Nevertheless even if Mississippi has a higher GDP per capita than the UK, all this really tells us, is that the United States has a higher GDP per capita than the UK. We knew that already. What we can show with the existing statistics, is that regional inequality in the EU is far greater than in the United States. Inner London is ten times ‘richer’ in terms of simple GDP than northeastern Romania. There are recognised distortions in the figures: the huge financial sector distorts the Inner London figure, for instance. Even allowing for that, the US has done much better then the EU in evening out regional disparities.

But is that due to the welfare state or lack of it? Probably not, since long-term factors are important, older the the welfare state. The US has had a single currency for two centuries, Romania has not even introduced the Euro yet. The US had a single labour market by the end of the 19th century. Internal migration rates were also much higher in the US, and the migrants took their education and skills with them.

Nevertheless, the people who quote this shibboleth, about European welfare states being poorer than the poorest US state, are convinced that it proves their point. That is the political reality which need to be addressed. I suggested in another comment that the state such address such claims as indicative of an inability to participate in the political community. Blind faith in isolated examples leads to absolute rejection of those who dispute them, and that will in turn lead to political repression and violence.

You will notice that the paragraph from which you removed my sentence starts with:

I was looking at average wealth, not inequality. Moreover, US states real GDPs and per capita GDPs are not difficult to compile at all, you can find them here: https://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/regional/gdp_state/2015/xls/gsp0615.xlsx . There is no back-of-the-envelope calculation. These are compiled by the US government. GDP is the most easily available data from everything I cited. There isn’t even a calculation to be made here, except with the interstate PPP adjustments.

No, the figures you quote don’t tell us anything about increases in either inequality or average wealth or total wealth, because they are not a time series. You don’t quote any figure for the ‘total wealth’ of the US, or the UK, or Mississippi. You don’t cite any figure for ‘average wealth’. The only figure you give on wealth, in figure 1 , relates to household wealth in the US, and then only to the share of the upper percentiles in the total.

No, there are apparently no figures for comparative regional GDP per capita at PPP, between US states and EU countries or region. That would require analysis of the price levels in each and every region compared. The spread sheet you cite contains internal, domestic United States figures. It does not say anything about other countries, and it uses national price levels anyway.

You can’t simply take the US figures for regional GDP disparities and the EU figures for regional GDP disparities at PPP, multiply them by the EU/US GDP ratio, and get an accurate figure for a UK – Mississippi comparison, for instance. Why not? Because the methodology is not standardised, especially not for price levels. That’s why the original Spectator post included such a back-of-the envelope calculation. Of course the statistics give a rough idea of the ratio. A rural region in Albania will be poorer than the poorest US state, for instance. So yes, perhaps Mississippi has a higher GDP per capita than the UK, but then that does not tell us what changes there have been in GDP, in either unit. So it cannot say anything about “increases in inequality”.

You don’t seem to understand some of the relevant indicators, or the difference between current indicators and time series, and you use extremely vague terms such as ‘accumulated wealth’ without giving any definition.

For what it’s worth, Eurostat table tec00114 gives the 2014 ratios between the EU27 and the United States per capita PPS GDP as 100 to 151. For the United Kingdom it is 108 to 151. With that sort of margin you would need large inequalities between states to make any US state ‘poorer than the UK’. On the other hand, the ratio for Norway is 179 to 151. Perhaps the Nordic welfare state model does work, or perhaps it helps to have a lot of oil and gas. More likely, we should avoid drawing sweeping conclusions about different models of society, on the basis of limited economic statistics.

Yes, you are right. I did not say they were about increases on inequality, average or total wealth. They were about average and total wealth at a particular time.

France’s figure is the sum of all assets owned by all households, all institutions and the State, minus all liabilities. I don’t understand why you are taking issue with this. Could you elaborate a bit more on why total assets minus total liabilities is not total wealth? I’m honestly curious here. I don’t mention US total wealth as it is sufficient to show its GDP is bigger than France’s total wealth, this already implies US total wealth (which is $123.8 trillion, by the way) is much higher.

I cited GDP per capita, which is not the best measure of average wealth but it does correlate with it, and it is often used in that context. I included it because I had already discussed average income and proven my point there, and because there weren’t good data for mean wealth in Germany for around 1998. Perhaps, I could have talked about average disposable income and made a similar point, but then I would have been just repeating myself.

Moreover, the purpose of this paragraph you keep concentrating on was arguing that even if I was wrong about the US having no less poverty at the bottom (meaning less of the relevant inequality), it could still be the case that US higher average and total wealth would compensate for that loss in equality. It was a side-point, thus less developed than the rest. Even if refuted, all the points of my main argument would remain.

Overall, it seems you are inflating my claims or misunderstanding the argument of each paragraph. Truly, this might have been partially my fault when structuring the paragraphs and I will correct some of these issues in the post. On the other hand, I’m not sure how much clear can it get in some cases. I’ve said: “…increases in inequality could be outweighed by higher total and average wealth. Let’s look at those figures.”, and you went on to attack the paragraph as if it purported to talk about increases in total and average wealth over time.

Evidently, any statistic will always be a partial picture. You can list all the limitations of any dataset, but unless you counter-argue with better data, then you are not making any point. It might as well be that finer data show I’m wrong, or that I’m right. Nonetheless, in the absence of better data you cannot just ignore what the current data suggests. I’ve provided a lot of data, all suggesting (but not proving) the same trend of no less poverty at the bottom and more wealth at the top in the US versus most welfare States. Stating these data have limitations is a vacuous point unless you provide better data suggesting something else.

What you first said about Germany is simply that “In 1988, the US inflation-adjusted GDP per capita was the same as the current German figure; after 1988 there was not a single year where Germany had average wealth higher than the US. ”

Now you write “… there weren’t good data for mean wealth in Germany for around 1998. Perhaps, I could have talked about average disposable income and made a similar point, but then I would have been just repeating myself.”

GDP per capita is not the same as average wealth. You don’t give a definition for ‘average wealth’ anyway. Disposable income is not the same as GDP per capita. Disposable income is not the same as ‘wealth’, whatever the exact definition of wealth. 1988 is not the same as 1998. Germany in 1988 is not the same as Germany in 1998. There were two Germany’s in 1988. German GDP per capita, today or in 1998, is not comparable with GDP per capita in the Federal Republic of Germany in 1988, because the BRD subsequently absorbed the DDR. (Population increased by about 25%, so any per capita data is non-comparable).

Sorry, but you do not seem to understand the data you are using. You can’t simply replace one indicator by another, and excuse it by saying they are ‘correlated’. I suggest you rewrite this post, and start by stating the ‘main argument’ explicitly, because that is not clear either.

Quote: I believe this is, in fact, a somewhat accurate picture of US inequality, as far as two-line analogies go. But it is no soul-crushing fact. Does a bar suddenly become worse because Bill Gates walked in? The other 10 people did not get poorer. In real-life America, most of them actually got richer.

Thus proving Joao misrepresents ‘inequality’ – whilst widening inequality gets ever wider. We still have the poor whilst the rich get richer.

Joao pretends to have no idea of what inequality is – knowing it is not about raising the average wage. The Gini coefficient is not a simplistic measure of inequality – it is a statistical confidence trick to hide ever growing inequality between a countries powerful rich families from the rest of population.

If the government measured weight problems by ignoring the obese and dangerously underweight – you would say they were corrupt and trying to hide the problems – wouldn’t you? That is how they measure inequality with the Gini – ignore the richest and poorest groups – those millions of people most affected by what is being measured.

The Gini is a con to make people believe that government are addressing inequality and are reigning it back in, when the truth is it gets worse every year. They lie, so when they show you the Gini go down any year you believe that inequality does.

Indeed, the UK Statistics Authority actually admitted to me the Gini “is not ideal if your particular interest is in inequalities at the top or bottom of the spectrum”. This is the first time I heard they disclosed the fact they know it is “not ideal” for showing the inequalities of the rich or poor. Thus proving they know it is a con.

They should know extremes have to be included as it is an essential factor in making the derived analysis more accurate. Yet they ignore this fact. The only logical reason to ignore the poorest and richest groups is to hide how bad inequality is. They deliberately dumb down that which they measure.

Gini would have to be a stupid mathematician not to understand this.

I made a video simple enough for a school kid to understand – yet too difficult for the ONS it seems. Pure intellectual cowardice.

Google: How we are conned: Inequality, Tax and Corporations

On the general issue of the route to equality, there are two important points to note.

First, the actual conditions of life matter more to the underclass, than either income or wealth. Two families in developing countries might have the same income and the same small amount of goods, but one has clean drinking water and the other drinks cholera-infected and polluted river water. One might have a life expectancy of 60 years and the other 40. A serious ethical assessment of which strategy will benefit them, need to take account of their actual conditions, and the possibility that they might gain financially, but that their conditions worsen.

That matters because there are real-world examples of those who gain financially, but whose life is worsened in the process. Improving family income by child prostitution is an obvious example: it works in economic terms. Even in developed countries, it is easy to find these who earn a little more than they otherwise might, but suffer appalling living and working conditions. Typically they would be illegal immigrants.

So even if you can show that a specific economic and social policy does reduce income inequality, you need to take account of the collateral damage to asses its impact on true ‘well-being’. There are some statistical measures which can help in that assessment – if income is rising for the underclass, but addiction, alcoholism, suicide and depression are also on the rise, then things are going wrong.

Secondly because of this impact, the choice of what trade-offs to accept must be left to the individual. Again the problem is obvious in the real world: the underclass might improve their income over time, but they will usually do that by working long hours in the worst jobs. In terms of the harm that is done, they would probably be better off staying poor. Prostitution is once again a classic example.

So the decisions on equality and trade-offs should not be made as a society. Do we want the poor to be better off in absolute terms with rising average incomes, or in relative terms with declining or static average incomes? We should not answer the question at all – we should leave it to each individual to decide. Now that means in practice that economic and social policy must be totally restructured, because at present there is one policy for all, without differentiation. The transition to individual choice would require new structures, and new legislation, which will inevitably impact third parties.

A typical example from real life is the fast-food sector, which western governments generally favour and assist, because it generates so many jobs for the low-skilled unemployed. If we took individual preferences into account, the workers in the fast-food sector might prefer that the government squeezed the sector out of existence, for instance with ‘fat taxes’ and public health restrictions. They might be worse off, but they would not have to work in that sector anymore.

Some considerations:

1) The focus on income puts aside that what really matters is not income, but dignity and freedom (which are inseparable). There are several examples of good public policy being held around the world, even in extremely poor countries, which have great impact on people’s quality of life. A liberal state tends to avoid this type of initiative. In other words, even if the distributive model implies less growth, maybe being poorer is better, considering the trade off as being less wealth = more quality of life.

2) One aspect that I see as very important in discussions of inequality is the distribution of power. Money is power, especially in a world where most of the population lives in poverty. Who have savings, especially the top 1% who accumulate 50% of the world’s wealth, literally choose which direction our aggregate social work will be directed. He who pays the piper calls the tune. How can we think of effective democracy, or a world community with decision power, if a few concentrated so much power? If this 1% wanted to stop the economy on the planet, they could. In fact, they already kind do this in cycles of economic crisis.

3) Today we have a level of wealth on the planet like never before, and this could be being directed to meet as best as possible the public interest. In this structure with highly concentrated income, this process is impaired since the decision on what to do with all this wealth is largely in the private sphere of a few individuals. As with the US selfless philanthropists, they may decide to generously donate half or more of their fortunes to social projects, but to me it does not seem appropriate for this type of decision to be individual, or even dissociated of the group it is supposed to benefit. How can the decision such as if a few hundred million Africans will or will not have minimal living conditions be in the hands of four or five US citizens?

Anyway, these are points that concern the inequality itself, not its economic effects. Of course, the discussion does not end there. And I think the pro-state people fail by not recognizing the technical difficulties that exist in the debate.

From these arguments I propose two goals: poverty reduction / eradication of poverty and reducing inequalities.

1st question that needs to be answered well, and so far I have not had contact with any thorough, methodical and convincing survey: the experiences we have to date indicate that these targets are compatible? They indicate that they are correlated? In which way? – This text, and others I have read, points to an inverse correlation, but it’s not conclusive research.

If indeed the strategies we have developed to deal with these two problems show they are contradictory, then we must either choose which of the goals will be a priority or develop a new strategy to encompass both at once.

From my experience in the state, I now think that the answer lies in its modernization and professionalization: much is said, and rightly so, about how much the state is ineffective and inefficient. But the maturing of public institutions, coupled with the incorporation of new technologies, seem to have great potential to change this. Improve the quality of public expenditure seems a relatively simple goal, with very high impact, and that has, so far, received little social attention.

Of course, these are strategies for the long term. In the short term, I think the most sensible way is to focus on poverty reduction policies, leading them or not to increased inequalities.

Comments are closed.