By Doug McConnell

Recently many of the staff at an aged-care home in Sydney, Australia called in sick the day after the report of a CoVid-19 outbreak at that facility.1 Upon investigation of these absences, one of the reasons the workers gave was that they were concerned about protecting their own families. They didn’t want to act as a vector transferring the disease from the aged care home to their own homes. So how much risk should social care workers and their families be obliged to take when responding to infectious diseases like CoVid-19?

Let’s begin by looking at how much risk individuals should be expected to take before considering how much risk their families should be expected to take. As a starting point, it’s widely agreed that we all have a duty of ‘easy rescue’ – if you see a child drowning in a pond there is a moral obligation to try and save them since the risk is minimal. But potential rescuers are not obliged to try and save others when it would involve higher risk, e.g. one isn’t expected to seriously risk one’s live to save a drowning child. There is a threshold, somewhere between the easy and the dangerous rescue, where the risks to a potential rescuer become so high that they are no longer morally obliged to attempt the rescue. To attempt the rescue in those dangerous cases would be supererogatory. This picture becomes more complicated when we introduce special skills and roles that have implicit (or explicit) social contracts.

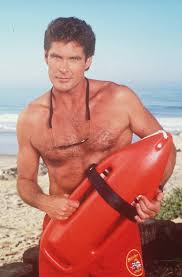

Lifeguards, for example, have special skills (and access to resources) that mean they are better placed to help someone drowning. Some of these skills (e.g. being a good swimmer) lower the risks to the lifeguard. Such skills increase the range of easy rescues the lifeguard is morally obliged to conduct because some sea conditions that are dangerous for weak swimmers just aren’t dangerous for lifeguards.

Lifeguards, for example, have special skills (and access to resources) that mean they are better placed to help someone drowning. Some of these skills (e.g. being a good swimmer) lower the risks to the lifeguard. Such skills increase the range of easy rescues the lifeguard is morally obliged to conduct because some sea conditions that are dangerous for weak swimmers just aren’t dangerous for lifeguards.

Other skills don’t decrease the risk to the lifeguard but increase the expected benefit of the rescue attempt (e.g. being good at resuscitating people). Skills of delivering benefits aren’t usually thought to increase the personal risk that the lifeguard should take, however, because the lifeguard’s life is worth just as much the drowning person. So the lifeguard isn’t obliged to take any more risk to conduct the rescue even if she knows that (somehow) saving this person would deliver twice as much wellbeing to that person as the lifeguard would have in her own life. Some utilitarians might dispute this, of course, but I won’t pursue that here.

Skills of delivering benefits do, however, eliminate excuses that others might have to not attempt the rescue. For example, if a person was justified in believing that their attempted rescue, while not personally risky, would be futile, then that would excuse the rescue attempt. The lifeguard’s skills of delivering benefits mean there are fewer situations where she has the excuse that it would be futile to try.

In summary, special skills that lower the personal risk of rescuing others and/or that ensure the benefits of rescue are delivered increase the range of situations where rescue attempts should be made but they don’t raise the absolute risk a rescuer should take to save another.

An obligation to take on extra risk arguably does come with consenting to take on a role set out explicitly in an employment contract or implicitly in a social contract. Based on that consent, the person who chose to be a lifeguard has a moral obligation (while on duty) to save drowning people. This involves taking on the risk of rescuing people even when there are other potential rescuers present but also, I think, taking on somewhat more risk than would be expected of someone who has the skills but hasn’t taken the role. Quite how much more risk depends on what was consented to. Employment contracts don’t usually spell this out, so any obligation to take extra risk is based on the implicit consent to a social expectation of what a lifeguard should do. It’s a bit vague how much extra risk is required here. It depends on local social expectations and it’s difficult to set clear rules, given the wide range of variables that contribute to the risk involved in any potential rescue. That said, I think there are cases where a lifeguard could be blamed for not attempting a risky rescue where a bystander with the same skills would not be. There is, of course, an upper limit on the risk demanded of lifeguards. They are not obliged to swim out into a tsunami to try and save someone from drowning and, if expectations were set that high, it would be difficult to find anyone prepared to be a lifeguard.

With these points in mind lets return to the case of social care workers at aged care homes. What is the risk posed to them by CoVid-19? Do they have skills relevant to reducing their own risk and/or saving elderly people at the home? What did they consent to in taking this role?

Elderly people in a rest home are typically in need of care. To leave them without care puts their lives at risk. This is especially the case when there has been a CoVid-19 outbreak which has been shown to disproportionately harm older people.

What risk does CoVid-19 pose to the social care workers? For people of ‘working age’ with no underlying health conditions, the risk seems fairly low. Infection appears to consist of a mild or moderate illness with <1% fatality rate. The risk to most of the workers in providing care is much less than to the residents of the aged care home of being left without that care. Arguably these facts alone mean that the conditions for easy rescue are met and so the social care workers are morally obliged to work (at least before we take the workers’ families into account). But for those who think these conditions are too risky to count as easy rescue, there are further reasons why the social care workers should turn up to work in this case.

The social care workers should have special skills that decrease the risks they face in treating people with infectious diseases given the well-known danger infectious diseases pose to patients in aged care facilities. Social care workers also have skills for delivering benefits to the elderly through their care and so there is no excuse that their work would be futile. If these social care workers did not have these skills, then they should be trained to have them. We wouldn’t take on people as lifeguards without giving them the opportunities to learn to be good lifeguards.

As argued above, these two categories of skills do not increase the absolute risk that a worker is obliged to face to try and save another, but they do increase the range of interventions the healthcare worker should make. Arguably that range of interventions would include providing care to the elderly while risking infection with CoVid-19. For those who suspect that the social care workers’ skills don’t sufficiently reduce the risk they face, so these conditions still don’t count as easy rescues, we are yet to consider the normative force of their consent to being a social care worker.

Perhaps the strongest reason that the social care workers should work in these conditions derives from the implicit social contract involved in choosing to be a social care worker. Society expects social care workers to provide social care in the facilities where they are employed. Much of that expectation is formalised in an employment contract, but the social contract also involves the implicit expectation that social care workers will take on greater risk (than the usual threshold for easy rescue) in providing the care necessary to keep the elderly residents of the facility alive.

But how much more risk is it fair to expect they take? As with the case of the lifeguard, the implicit risk involved in the social expectations of a role is difficult to quantify. I think the risk to these workers (assuming they are not in the vulnerable categories) is relatively low and so the normative demands of the social care worker role are sufficient to entail an obligation to work in a CoVid-19 outbreak.2 Unfortunately, social care workers are undervalued by society and so perhaps it is unsurprising that many think they shouldn’t have to take on much risk to provide care. Some might seize on this point to claim that society didn’t think they needed to expect much of social care workers and so the implicit social contract did not oblige social care workers to take this level of risk. In which case, we can’t blame the social care workers for staying home but we can now see that we were mistaken to expect so little of them. In either case, we need to clarify the expectations of social care workers and increase the pay and prestige of the role so that its commensurate with an obligation to provide care in risky situations.

As an aside, the UK government has recently floated the idea that people in aged care facilities could be ‘cocooned’ to protect them from infection.3 Presumably this would require social care workers to test negative for CoVid-19 before working and to remain in the ‘cocoon’ for extended periods of time. In recognition that this role would be much more demanding than what is expected of social care workers, volunteers for this new role would have to be sought.

Let’s turn now to consider the risk infectious diseases pose to social care workers’ families. The social care workers who refused to work claimed to be motivated out of concern for their families, especially in two cases where the family members were immunocompromised. Do these concerns for one’s family reduce the obligation of the social care worker to work? The family members didn’t take on the professional duties of being a social care worker so why should they take the risks?

Another way to look at this problem is to ask – how much should we expect workers to do to meet their obligation to protect their families? If the efforts required of workers to protect their families is more than can be reasonably expected of them given the normative demands of their professional role then the family considerations might excuse them from working in a pandemic.

Another factor here is that these family members are at some risk of contracting CoVid-19 in their daily lives anyway. So, it depends how much extra risk the healthcare worker is responsible for managing. If the family members were just as likely to become infected anyway, then the social care worker may as well go to work, since it doesn’t matter who the vector is. In this case the social care workers certainly generate some extra risk of transmitting the infection to their families.

So, what would social care workers have to do to protect their families? The usual steps are not too strenuous, e.g. regular hand washing, cleaning potentially contaminated surfaces, and self-isolation if they do happen to become sick. Of course, these steps are not certain to prevent contracting and passing on the infection but as long as they reduce the risk to roughly the risk of becoming infected anyway then it is sufficient.

What about those social care workers with immunocompromised family members? The acceptable risk of infection is much lower for these family members given the higher chance they would die if infected. Therefore, the social care worker would have to take much more rigorous actions to prevent transmission, such as undergoing a week of quarantine before returning to close proximity with those family members. I don’t think social care workers should have to take on this burden, especially since it would prevent them from providing care for those vulnerably family members. As a general rule, we can say that the more vulnerable one’s family to an infectious disease, the more excusing it is of any professional obligations to care for infectious people.

In my view, then, the social care workers with highly vulnerable family members are justified in not working in the context of a CoVid-19 outbreak, but the social care workers whose families are not particularly vulnerable should work. More generally, if we want social care workers to provide a high standard of care in situations that are risky for them and their families, we should provide training to help them lower that risk, payment to compensate for that risk, and a greater level of esteem befitting someone who cares for vulnerable people despite such risk.

Footnotes

- Wahlquist, C. “Coronavirus: union defends staff of Sydney aged care home after ‘most’ call in sick”, 5th March, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/05/coronavirus-union-defends-staff-of-sydney-aged-care-home-after-most-call-in-sick

- The normative demands of the social care worker’s role are much less than that of other healthcare professionals such as doctors. The professional role of a doctor involves an obligation to work even in the context of a much more deadly pandemic than CoVid-19. These high professional obligations also entail that they we can ask doctors to make greater sacrifices to protect their families, such as by forgoing close proximity with their families for long periods. There have been no reports, as far as I am aware, of doctors refusing to work in the CoVid-19 outbreak.

- Easton, M. “Coronavirus: Care home residents could be ‘cocooned’”, 11th March 2020, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-51828000

In some ways I feel it would be beneficial to have the conversation of how many people are coming into contact with older individuals within one day. Maybe there needs to be only a select few. Which seems to be what the article is suggesting.

Another interesting thought I had was maybe even taking into consideration the views of the elderly in another way. How should they feel when people are coming and going from where they live. I understand these people are responsible for saving their lives. Although these feelings seem very important to the situation. I would be open to discuss this more. Maybe there needs to be an incentive for health professionals to receive training which could solve these dilemmas.

In the current epidemic there is lots of angry reporting about deaths among health workers as if they were all caused by exposure through work. I know it may not be liked, but I wish he reports had a bit of data analysis to go with it. The number of health workers in the UK is significant – about 4% of working population – this would mean a significant number of the cases (and deaths) might be expected in the health worker population, irrespective of the work exposure.

My basic analysis would suggest that the health workers are under represented in the number of deaths. I probably don’t have access to enough data details, but that’s my suspicion – I expect those that have access to the data (the health organisations) wouldn’t like to do the analysis in case … it points at a particular occupation, that is not health work – with Johnson, Trudeau etc. it seems senior political work is!

Comments are closed.