by Anders Sandberg – Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford

by Anders Sandberg – Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford

Is there a future for humans in art? Over the last few weeks the question has been loudly debated online, as machine learning did a surprise charge into making pictures. One image won a state art fair. But artists complain that the AI art is actually a rehash of their art, a form of automated plagiarism that threatens their livelihood.

How do we ethically navigate the turbulent waters of human and machine creativity, business demands, and rapid technological change? Is it even possible?

Rise of the AI “artist”

Computer generated art has a long tradition, running from 1960s experiments using plotters and teletype output over AI artists to installations, virtual reality and paintings sold at auctions.

Much has been written about the role of the human creators in making the “artist” and selecting what output to hang on the walls. So far AI art has more been humans interacting with a system that produces output that is called art, rather than having a temperamental computer deciding to drop doing spreadsheets and instead express itself – but that might have been less controversial than the current AI art situation.

What happened recently is that machine learning moved from just categorizing images into synthesizing images and this was linked to language models that can describe images: prompt the system with “A masterpiece painting of Oxford by Thomas Cole. Warm light” and 10 seconds later we get a passable scene with lawns, gothic spires and sunshine.

What happened recently is that machine learning moved from just categorizing images into synthesizing images and this was linked to language models that can describe images: prompt the system with “A masterpiece painting of Oxford by Thomas Cole. Warm light” and 10 seconds later we get a passable scene with lawns, gothic spires and sunshine.

The transition has been fast: this time last year the best programs could only work in limited domains (anime faces, cats, MPs…) or produced distorted, surreal output. But month by month innovation happened. By April 2022 OpenAI’s DALL·E 2 produced a jump in quality: many online commenters refused to believe the output wasn’t done by a human! Over summer new techniques like Stable Diffusion were invented and released publicly – by early fall the Internet was suddenly deluged by AI art. The exponential improvement is ongoing.

Reactions from online artists were sour. Beside claims the art was soulless and derivative, there were more substantive claims: this threatens illustration work, something many artists do to pay the rent, and the models had been trained on pictures found on the internet – the work of the artists themselves, now used to compete with them without compensation.

Morally, do magazines have to source their images from humans? Do the artists have a claim on the neural network contents and output since it was their work that formed the training set?

Locally sourced Fairtrade organic art

A classic debate as old as the industrial revolution is when automation replaces or complements human work. Some jobs disappeared (lamplighters), some were augmented (farmers). Magazine illustration may be a case where either could happen, a bit like during the introduction of photography. It might be cheaper, faster and even more on-topic if illustrations are generated by AI than by commissioning an artist… or it could be that artists overcome their initial distaste just as they did with Photoshop and Illustrator and instead employ AI to fill in the boring parts, come up with ideas they then select among, or do entirely new creative solutions. This is fundamentally unpredictable.

One could demand that just as we pay extra for organic locally sourced food (essentially, inefficiently produced food fitting out aesthetic and ethical preferences) we should pay extra for organic human art. Given the tiny economic margins for most magazines economic incentives will work against this unless it either becomes a major branding theme (“our magazine, unlike our competitors, is 100% written and drawn by humans like you!”) or one tries a collective bargaining solution mandating human-made. That likely requires government or union support and is going to make artists rather dependent on external organizations. Meanwhile blogs and other unregulated media that previously could not afford human-made illustration will be replete with AI-made illustration, perhaps competing more effectively.

Do we have a duty to support artists by supporting their illustration work? Many artists likely do not see it as anything but a chore and might be happy with a direct cash transfer rather than having to churn out yet another political cartoon when they want to work on their masterpiece. Others do enjoy it, both as art on its own and as training: here the commissioned work matters to them, and mere payment would not substitute.

There are many crafts we appreciate not just for their practical output, but for their role in our culture, history, the aesthetics of the process and so on. In many cases we do use collective action to support them, whether by national endowments to art or sometimes by explicitly naming people as living national treasures.

It could well be that this may happen to human artists. That will likely be a fraught process since such collective help always comes with strings attached – is anybody doing anything art-like eligible, or only good artists? Do your art have to fit mainstream values, or are any values OK?

Who owns the visual world?

The other big ethical issue is the ownership of the training data. Typically it is scraped from the Internet, a vast trawl for any picture with a description that is then used to train a neural network. At the end the sum total of human imagery forms an opaque four gigabyte file that can be used to generate nearly any image.

Sometimes the images look very similar to training images, making people talk about plagiarism. But that compressed representation doesn’t have the space for direct copies: it actually generates images anew from its extremely abstract internal representation. It is literally transformational use. If the output looks exactly like a particular input it is likely more due the input being something very archetypal.

The real challenge is the use of styles: asking for an Oxford picture in general will not make as nice picture as when tweaked by adding “in the style of…” A vast number of prompting tricks has been discovered, ranging from adding “trending on ArtStation” or “a masterpiece” to finding artists with particular styles the network “gets” well. The result is that by now there are far more pictures in the style of Greg Rutkowski than he ever made. And he is not happy about it.

There is a host of intellectual property and ethical issues here.

Did the artists give permission for their images to be used like this? They probably do not think so, but were they to scrutinize the endless and unreadable user agreements of the sites they display images on they might well discover that they agreed to allow automatic searches and processing of images. The sites might perhaps have a stronger legal claim against the AI companies than the artists. Still, the legal issues will keep IP lawyers talking for years: the situation is anything but clear-cut, and different jurisdictions will have different norms.

It is not possible to remove a particular artist from the network at present: their art is a subtle set of correlations between billions of numbers, rather than a set of artworks stored in a database. In the future maybe ethical guidelines may require the web scraping to only use public domain images (but how do you tell which are which? If you only use explicitly public images much of art history and human imagery will be blocked off), or make use of watermarks to ignore certain images (Stable Diffusion uses this to prevent re-learning its own output; various industry and artist consortia are trying to impose a standard for excluding their artworks). But right now all online images contribute to the same four gigabyte file.

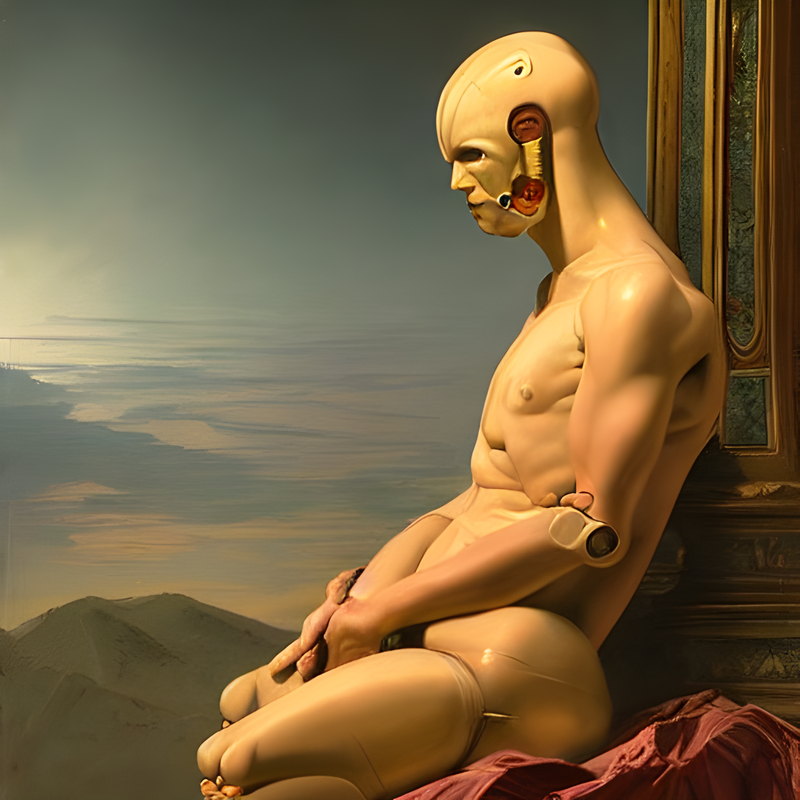

It is also tough to claim to own a particular style or technique. Generally, art styles cannot be trademarked under IP law because they do not constitute products or services, and being mental processes they cannot be patented. Indeed, it might be easier to patent a neural network (an actual product) imitating Greg Rutkowski than protect his style. We may agree that morally, imitating somebody’s style is bad form, due to the lack of creativity and individuality. But one of the most common techniques in prompt-making is to combine styles from several artists. For my own roleplaying game illustrations I have tried using “by Roberto Ferri, Zack Snyder and Thomas Cole” to get baroque bodies, action scenes, and nice backgrounds: these pictures are unlike what any of them would individually have made. Am I then infringing morally on their style?

It is also tough to claim to own a particular style or technique. Generally, art styles cannot be trademarked under IP law because they do not constitute products or services, and being mental processes they cannot be patented. Indeed, it might be easier to patent a neural network (an actual product) imitating Greg Rutkowski than protect his style. We may agree that morally, imitating somebody’s style is bad form, due to the lack of creativity and individuality. But one of the most common techniques in prompt-making is to combine styles from several artists. For my own roleplaying game illustrations I have tried using “by Roberto Ferri, Zack Snyder and Thomas Cole” to get baroque bodies, action scenes, and nice backgrounds: these pictures are unlike what any of them would individually have made. Am I then infringing morally on their style?

It is worth noting that humans are constantly taking imagery and using it without permission. There is thick spectrum here ranging from just copying without credit, over the mood-board where the image uncredited becomes part of something else, to tracing it while making one’s own image, training by imitation, to influencing future artists by style or content. Some of these are regarded as legally or morally inappropriate. What the network is doing is more akin to learning art by seeing all of it and forming an internal representation than just tracing out a copy. If we accept humans learning by imitation and visual experience we may have to accept AI doing it…

…yet the complexities about appropriate use of art involve not just what is being done, but by whom and why. Tracing images is sometimes acceptable, sometimes not, depending on the local art community norms, how much credit is being given to the original creator, and how transformative the result is – very subtle issues. These issues can and are resolved differently in different communities: cartoonists, furry artists, painters, computer artists, and designers each have their own (more or less) consensus views. Current AI art cuts across all art communities and usage types, ignoring the local normative equilibria.

The big ethical problem here is not so much what is appropriate use or not, but that the same tool affects everybody at the same time in the same way. There has not been time to come up with the nuances on how it should be used, and large numbers of very different stakeholders have suddenly shown up at the artists’ door, kicking it in.

Reflective equilibrium in a turbulent lake

Is art and pictures a common good that we want to be expressed freely and widely by anyone wanting to create? Or is it imperative that creators of new imagery have control over how it is used?

Most people would presumably nod at both sentences, but they contradict each other. AI generated imagery draws on the common pool and democratizes much image generation, often in creative ways through prompt writing, selecting the best output or entirely new visual forms. But this threatens the current livelihood of artists. Yet the institutional and technical reforms suggested – collective bargaining for ensuring human imagery, restrictions on what types of creation are allowed in different forums, improving intellectual property control using metadata – are limiting many forms of creative freedom.

This gets further complicated by the gatekeeper role of the AI companies. Dalle-2 was carefully trained so it would not generate pornographic, violent or political imagery. Many of the AI art platforms also implement filters preventing outputs an algorithm estimates to be too naughty. However, many forms of valid artistic expression is sexual, violent or political, and the filters frequently misfire. Again there is a nontrivial balance between freedom of human expression, community norms, companies legitimately not wanting to touch too controversial topics. If only some kinds of art can be created (or transmitted) using standard platforms it might flatten creativity in a way that would make a puritan censor drool.

Finding a moral reflective equilibrium requires locating a balance between general principles (creative freedom in art and technology, moral rights to one’s creations, …) and particular issues (the nature of Internet, globalization, the business of imagery, censorship, …) Traditionally this has happened over time and in relatively small communities, with plenty of time for emotions to calm. We are entering an era where technological change may be too fast and too global for this to happen: as we seek to find the balance the game changes, since practical underpinnings and our intuitions (including who “we” are) change, and there is no stable point.

In Carl Frey and Michael Osborne’s 2013 paper analyzing how automatable jobs may be, “Fine Artists, Including Painters, Sculptors, and Illustrators” is assigned merely 4.2% probability of seeing their jobs transformed. That turned out to be surprisingly wrong. We should expect similar surprises (in either direction) for many other jobs. We will have to have similar conversations as this over the coming years in many domains – and we may need to figure out ways of achieving quick-and-dirty approximations to reflective equilibria faster. Maybe that is a job for AI philosophers.

It appears to me that you are discussing a phenomena in art not a transition to computer art. Now, as always art and beauty are in the eye of the beholder.

Well, whether artists can successfully sell their work to magazines or not seems to be fairly objective.

Where did I see it mentioned that certain AI art programs trained on copyrighted material from companies like Disney, Sanrio, and Nintendo? While they might want the programs for themselves, I’m sure they will not want other companies to use these AI programs with their IP in it. As it is now these programs are just IP laundering machines used to circumvent copyright law

“With their IP in it” is the tricky question. I have seen Mickey Mouse, and if I draw a cartoon mouse I am at least in some sense influenced by Disney IP no matter what it looks like. One can easily argue that my cartoon mouse is transformative and hence OK (assuming it doesn’t look exactly like Mickey). But this applies to the machine learning system too. So saying they are just IP laundering machines is like saying artists are just IP laundering machines.

I am not an artist, therefore, my interests, preferences and motives have little to do with this aspect of AI research. There has been a discussion and comments on robot rights, on another blog over the past several days and a dozen or so people have put their thoughts into that. The blog owner, whom I respect, mentioned a knowledge explosion. I have previously mentioned what I see as a parallel issue, emergent perhaps from the old bug bear, political correctness. I coined social correctness, as a ‘term of art’—no play on the topic being addressed here. There are potential questions: 1. Is it socially correct or better, economically correct, to jeopardize legitimate careers? I do not know. But it seems to me that many successful artists chose their careers, before AI generated work came on the scene—other aspirants may think twice about it now. 2. Adding to social correctness,suppose we are compelled to devise some adjunct, say, moral correctness?, and, 3. What are necessary criteria for something, say, AI art, to BE morally correct? We have a lot of trouble with morals and ethics, as things now stand. My blog acquaintance’characterization, knowledge explosion, is not new. The notion has been around for sometime. Read Toffler (Future Shock; the Third Wave) if you have never done so. I will leave this there—for now…

After considering my first comments on this question, I had to accept the full implication of all of it. Firstly, in my opinion, a world lacking human art would be one lacking art. Period. AI art, in its’ limited sense, seems predictable in its’ sameness…an example of the mass production which gave us the Model T Ford. The car was predictable, reliable and cheap, for its’ time. But it was boring. Few people, save collectors, are interested in those cars now, their obsolescence notwithstanding. Secondly, even predictable and striking imagery wears thin if there are no alternatives. Sensory overload and sensory deprivation both ultimately lead to sensory numbness, when consistently inflicted. I could write an essay on this, but that would be pointless too…just another example of sensory overload, or, depending on POV (point-of-view), sensory deprivation.

Comments are closed.