Written by Muriel Leuenberger

A modified version of this post is forthcoming in Think edited by Stephen Law.

Spoiler warning: if you want to watch the movie Don’t Worry Darling, I advise you to not read this article beforehand (but definitely read it afterwards).

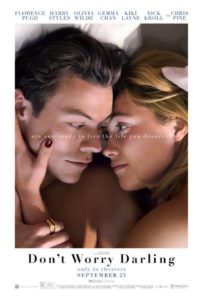

One of the most common reoccurring philosophical thought experiments in movies must be the simulation theory. The Matrix, The Truman Show, and Inception are only three of countless movies following the trope of “What if reality is a simulation?”. The most recent addition is Don’t Worry Darling by Olivia Wilde. In this movie, the main character Alice discovers that her idyllic 1950s-style housewife life in the company town of Victory, California, is a simulation. Some of the inhabitants of Victory (most men) are aware of this, such as her husband Jack who forced her into the simulation. Others (most women) share Alice’s unawareness. In the course of the movie, Alice’s memories of her real life return, and she manages to escape the simulation. This blog post is part of a series of articles in which Hazem Zohny, Mette Høeg, and I explore ethical issues connected to the simulation theory through the example of Don’t Worry Darling.

One question we may ask is whether living in a simulation, with a simulated and potentially altered body and mind, would entail giving up your true self or if you could come closer to it by freeing yourself from the constraints of reality. What does it mean to be true to yourself in a simulated world? Can you be real in a fake world with a fake body and fake memories? And would there be any value in trying to be authentic in a simulation?

One dimension of authenticity entails that you should know yourself, not be self-deluded, and face uncomfortable truths. Living in a simulation is inauthentic if it is done to escape reality. Alice’s friend Bunny is aware that she is in a simulation. She chose to live in the simulated town because there she could be with her children (a simulation of them, to be precise) who passed away in real life. The Victory project is a form of escapism for her. The self-awareness and self-knowledge required for authenticity extends beyond knowing your character, intentions, or actions to knowledge about what occurred in your life. There is no need to know every detail about one’s life in order to be authentic but choosing to delude herself about the death of her children seems like a failure to acknowledge fundamental realities about her life and thereby a failure to be authentic. (This is not to say that it isn’t understandable and in some cases maybe even beneficial to one’s mental health to delude oneself in highly traumatic circumstances.)

In contrast, Alice is unaware that she is in a simulation for most of the movie. She is forced into the simulation by her husband Jack. Her memories have been manipulated – she no longer remembers that she used to be a surgeon who was supporting her unemployed husband. Her personality, values, and other characteristics also seem to have been altered to make her fit into the role of a 50s housewife and give up any personal ambitions beyond fulfilling her husband’s wishes. In principle, even quite radical changes can be authentic (unless you want to hold on to the idea that everyone has an unchanging, essential true self). The problem with Alice’s change is that she did not choose it herself – it was imposed upon her. Authenticity demands independence in the sense that one should be free from certain pernicious external influences. Such extreme forms of brainwashing and manipulation prevent her from making independent choices about who she is and wants to be. Thereby, they certainly limit Alice’s capacity to be authentic.

Her husband Jack also changes upon entering the simulation. He looks better and his exceptional dancing abilities suggest that he also upgraded his skillset. However, in his case, those changes occur by his own choice. They can be understood as a project of self-creation. As a transgender character in the movie All About My Mother by Pedro Almodóvar says while showing off her silicone implants, “you are more and more authentic the more you look like someone you dreamed of being”. This existentialist dimension of authenticity demands that you take your life into your own hands and create yourself freely. It seems that such self-creation could also occur within a simulation in which you embody those changes. Thus, Jack can be considered more authentic within the simulation. Moreover, it seems unlikely that he is self-deceived regarding his real-world looks and abilities since he almost daily returns to the real world to work and check on his and Alice’s real-world bodies. The only dimension of authenticity Jack seems to be lacking is authenticity as a truthful expression of one’s thoughts and emotions. Because he constantly lies to his wife about their lives and what he did to her and does not openly stand for his own actions, he lacks authenticity as truthfulness.

A remaining question is whether there is any value in pursuing the ideal of authenticity within a fake, simulated world. Philosophical and empirical research suggests that authenticity is closely linked to meaning in life. More specifically, authenticity may lead to three key facets of meaning in life: coherence, purpose, and significance.[1] The component of significance seems to be particularly affected by leaving the real world for a simulated one. Significance represents how important, worthwhile, and inherently valuable life seems and whether one’s life matters in the sense that it has a lasting influence on the world. By living in a simulation, one is disconnected from the physical world and can no longer impact it. Children, who are for many people central to constitute meaning in life and a way to make a lasting impact on the world, are also simulated in the Victory project. The love and energy Bunny invests in her children run empty as there is no consciousness at the receiving end and once she leaves the program, the children will cease to exist. Life in the simulation does not bear any fruits, a theme picked up in the movie’s rather heavy-handed symbolism of empty eggs and a barren landscape.

The only real impact in this world is on the minds of the others that are plugged into the simulation. It seems possible to form meaningful and personally significant relationships within a simulated world. A meaningful and authentic simulated life could be feasible. However, at least in Don’t Worry Darling, the relationships seem to be highly superficial. The conversations don’t go beyond work, cars, and other possessions for men and shopping, household, and gossip for women. Because life in this Victory simulation is so utterly limited in significance and appears largely meaningless, the purpose of authenticity is also in question. The end at which the ideal of authenticity aims – meaning in life – is out of reach anyways, so why bother?

- Schlegel, Rebecca J., Patricia N. Holte, Joe Maffly-Kipp, Devin Guthrie, and Joshua A. Hicks. 2022. “Authenticity as a Pathway to Coherence, Purpose, and Significance.” In Experimental Philosophy of Identity and the Self, edited by Kevin Tobia, 169-181. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Is so interesting how much we can learn with the point of view from a professional.Wise words!

Clearly, I am missing a point here. Moreover, for “poor me”, I don’t even grasp what that point might be. How is it that we should simulate our true selves? Or, why should we need to do so? I rhetorically ask: how does simulation of one’s true self represent authenticity, other than falsely? In the sport of fencing, it is called a feint within a feint. One film you mention, The Truman Show, was clever postmodernism. Jim Carrey’s talent and genius made it work, rolling Escher, Orwell and Bradbury into one package of surrealism and phantasm, not necessarily in that order. Linguistically, simulation of a true self suggests something like the classic fencing ploy; or a martial arts distraction—deception to improve advantage. I mentioned the “poor me” characterization for these reasons or more. Years ago, Redfield wrote a charming, if not wise, fiction series based on something he called The Celestine Prophecy. He said there were four types of personality: intimidator; interrogator; poor me; and, aloof. SIMULATING one’s true self seems aloof. But, is that right? I hold it is not. Why? Because the other three Redfieldian designations also embody deception. And that, is how we get what we want.

Comments are closed.