Comment on “Bedside detection of awareness in the vegetative state: a cohort study” by Damian Cruse, Srivas Chennu, Camille Chatelle, Tristan A Bekinschtein, Davinia Fernández-Espejo, John D Pickard, Steven Laureys, Adrian M Owen. Published in The Lancet, online Nov 10.

Cruse and colleagues founds evidence of some kind of consciousness in 3 out of 16 patients diagnosed as being permanently unconscious. They used an EEG machine, capable of being deployed at the bedside. Is this good news?

This important scientific study raises more ethical questions than it answers. People who are deeply unconscious don’t suffer. But are these patients suffering? How bad is their life? Do they want to continue in that state? If they could express a desire, should it be respected?

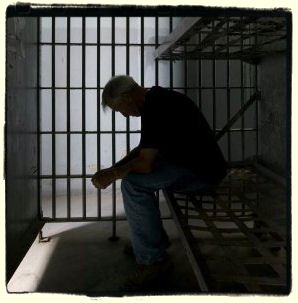

The impor tant ethical question is not: are they conscious? It is: in what way are they conscious? Ethically, we need answers to that. Life prolonging treatment has been and legally can be withdrawn from patients who are permanently unconsciousness. We need guidelines for when life-prolonging treatment should be withdrawn in these minimally conscious states. Paradoxically, it could be worse for some than being permanently unconscious. And in countries like the Netherlands, we need guidelines on whether and when active euthanasia should be performed. For some of these patients, consciousness could be the experience of a living hell.

tant ethical question is not: are they conscious? It is: in what way are they conscious? Ethically, we need answers to that. Life prolonging treatment has been and legally can be withdrawn from patients who are permanently unconsciousness. We need guidelines for when life-prolonging treatment should be withdrawn in these minimally conscious states. Paradoxically, it could be worse for some than being permanently unconscious. And in countries like the Netherlands, we need guidelines on whether and when active euthanasia should be performed. For some of these patients, consciousness could be the experience of a living hell.

Previous research by some of these authors shows importantly that some patients who are “locked-in” – who are clearly conscious and can communicated but cannot move at all – find their lives worth living. Even this finding would not settle what should be done. What makes each person’s own living hell is a matter for that person. It is subjective. And we can adapt to terrible disability. That is important for all of us to know. But it does not change the rights of individuals to make what they will of their lives, including choosing the conditions under which and the time to end them. One possible solution to these issues is to form a living will about what should happen to you, if you were to be in such a state (see: https://blog.practicalethics.ox.ac.uk/2011/02/ethical-lessons-from-locked-in-syndrome-what-is-a-living-hell/)

Such cases also raise ethical issues of futility and the appropriate allocation of limited resources on patients with severely impaired quality of life. That is, they raise questions of distributive justice. Even if such patients are minimally conscious, is it fair and just to use public resources to keep them alive for many years? Very poor quality of life has been used as ground for withholding or withdrawing medical treatment.

Science is invaluable in discovering what the world, including ourselves, is like. But it can never alone tell us what we should do. The big question – how such patients should be treated – remains as open as ever. We need more science to find out what the life of such patients is like. But we also need ethics to decide what we do when we discover that.

Further Reading

Kahane, G. san Savulescu, J. (2009). ‘Brain-Damaged Patients and the Moral Significance of Consciousness’. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy. 33: 1-21. doi:10.1093/jmp/jhn038

Skene, L., Wilkinson, D., Kahane, G., and Savulescu, J. (2009). ‘Neuroimaging and the Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Treatment from Patients in Vegetative State’. Medical Law Review. 17: 245-261. doi: 10.1093/medlaw/fwp 002 ISSN: 1464-3790

Wilkinson, D., Kahane, G., Horne, M., and Savulescu, J., (2009). ‘Functional Neuroimaging and Withdrawal of Life-sustaining Treatment from Vegetative Patients’. Journal of Medical Ethics. 35: 508-511.

Wilkinson, D., Kahane, G., and Savulescu, J., (2008). ‘Neglected Personhood’ and Neglected Questions: Remarks on the Moral Significance of Consciousness’, American Journal of Bioethics. 8:9 31- 33.

For more on distributive justice and limitation of life-prolonging medical treatment, see:

Wilkinson, D. and Savulescu, J. (2011) ‘Knowing when to stop: futility in the ICU’. Current Opinion in Anaesthiology April 2011 Vol: 24 (2) pp 160-165

Savulescu, J. (2001). ‘Resources, Down Syndrome and Cardiac Surgery’. British Medical Journal.322:875-6.

Thank you, Julian, for an interesting post. Two brief, related, comments :

1. I think it is unhelpful to categorise consciousness as being either « on » or « off » in these cases.

As you say : « SOME KIND of consciousness » has been detected in 1/5 of cases thought to be « permanently unconscious ». But these EEG-measured brain activities have very little to do with what we would normally call consciousness.

2. If we accept that the 1/5 of patients with positive EEGs are different from the others, and extend the recommendation to have this novel test and EEG machines at the disposal of all similar cases, what, in practice, will change ? If we switch off 13 life support systems, what will we do with the other 3 ? Will we wait 15 years as in the Schiavo case ? And what will we, or they, gain ?

(Sorry not to comment in detail on your attached reading list, but most of it is behind paywalls beyond my reach.)

If we were to agree that anyone with a lower level of consciousness were entitled to have their desires respected, then to me that implies we must also respect the desires of any animals with a similar level of consciousness. Whatever scientists discover about minimally conscious patients will impact on how we view and treat various animals (and in the future, AI); we can hardly justify treating the patients and animals differently if we believe they have a similar level of consciousness and quality of life.

Why the discussion about consciousness amongst some terminal patients, and not about the sacredness of life in general? We raise a perfectly healthy child, and in the prime of their youth, we send them to the battlefield to fight our unjust wars. We let people engage in some of the dangerous sports activities that can instantly kill the participant. We watch movies where stunt men/women perform some of the dangerous stunts that can easily take their lives. But, alas, no one says anything as if the importance of live depends upon specific circumstances. If it's the life we are talking about, then why don't the so called ethicist voice their opinion against all such activities that directly endanger human life? Why be specific? is it because the pharmaceutical industry funds many university programs – medical or ethics related – that encourages keeping terminal patients alive for an indefinite period of time? Who started the "National Breast Cancer Awareness Month" in 1985? Wasn't it AstraZeneca the "maker of the anti breast cancer drug?" From a utilitarian point of view, isn't the life of a conscious person worth more than the life of an unconsciousness person?

Khalid, with regards to your final question, the problem is that there is no clear dividing line between 'conscious' and 'unconscious'. I would agree that the life of a conscious person is worth more than the life of an irreversibly unconscious person. But what if someone is minimally conscious? At what level of consciousness is it necessary to take into account a human beings' well-being?

Obviously you raise a lot of other questions, but I think there are clear differences between the situation outlined in this blog, where individuals are in the care of other people, and people choosing to take part in dangerous sports activities, where (one hopes) they are aware of the risks beforehand but have still made the decision to go ahead with it.

Thank you for highlighting that not all of these were open access. We have had ongoing problems with this process and are taking steps to open these papers with the journals. In the meantime where possible the links in the blog are now the article pre-prints so I hope you can access them. The only exception is the BMJ 2001 article which is not covered by our open access agreement with the Wellcome Trust, and I do not any longer have a copy of the pre-print, only a journal off-print

Comments are closed.