Written by Alberto Giubilini

Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities

University of Oxford

Former UK supreme court justice and historian Lord Jonathan Sumption recently made the following claim:

“I don’t accept that all lives are of equal value. My children’s and my grandchildren’s life is worth much more than mine because they’ve got a lot more of it ahead. The whole concept of quality life years ahead is absolutely fundamental if one’s going to look at the value of these things.”

This wasn’t very well received, to say the least. Experts were quickly recruited by the press to rebut his claims. Headlines were made to convey people’s outrage at the idea that we can put a value on human life, and what is worse, different values on different human lives (which, by the way, is precisely what the NHS regularly does whenever it decides whom to put on a ventilator when there are not enough ventilators for everyone, or when it decides not provide life-saving treatments that cost more than £ 30k per quality-adjusted-life-year).

But the context of the discussion matters. These claims were made during a TV program which posed the question whether current lockdown was “punishing too many for the greater good”. That certain lives might be less valuable than others, for the purpose of pandemic management, is built into the very same question that was being asked. Admittedly, “punishing” was a bad choice of words. “Harming” would probably have been better to refer to a series of restrictive pandemic measures, and most notably lockdown.

Pandemic policies inevitably require us to make decisions about whom to prioritize when it comes not only to saving lives, but also to promoting health, wellbeing, and life expectancy. When we talk about lives in this context, we are not only talking about whose lives to save. We are also talking about the quality that such lives will have as a consequence of our decisions, the physical and mental health outcomes of such lives, and whether to “save” lives in the short term or lives in long term, considering for example that the level of unemployment in young generations caused by restrictive measures will likely negatively impact their life expectancy. (I would ask those who are troubled by the term ‘caused’ here to wait until I address the point below).

Importantly, Lord Sumption’s claims make it explicit how a question about the trade-offs involved by lockdown is inevitably also a question around intergenerational justice. Here I suggest that current lockdown policies are an unfair form of age-based discrimination against young generations. That is, in philosophical jargon, lockdowns are ageist. “Ageism” is often assumed to be a form of unfair age-based discrimination toward the elderly. But current lockdowns are ageist against the young, or so I will suggest.

The costs of lockdown are mostly on young generations, who are significantly less vulnerable to COVID-19 and significantly more affected by restrictions, both at present and in terms of medium and long term prospects. There are cases of “long covid” among the young, as there are cases of deaths. But these are rare and the most likely to experience lingering covid are the elderly and those with multiple serious medical conditions.

The benefits of lockdown mostly accrue to the elderly, who are significantly more vulnerable to COVID-19 with regard to risk of death and ‘long covid’, and significantly less impacted by restrictions.

The question is whether this form of unequal distribution of costs and benefits across generations is unfair.

If we want to ask the question and have a serious debate about this, we need to be prepared to accept uncomfortable answers, including the views that Lord Sumption’s has expressed. If we presuppose that such views are outrageously wrong and should not be expressed to begin with, we might as well avoid asking the questions and just go with common-sense narratives. Part of the outrage was due to the fact that a person with stage 4 bowel cancer was participating in the debate and felt (perhaps understandably) targeted by Lord Sumption’s claim. Cancer patients, even when young, are among the vulnerable people at higher risk from COVID-19. Because the kind of selective lockdown that Lord Sumption was defending would apply to all the vulnerable people, not just the elderly, she felt targeted by his remarks, although he clarified: “I didn’t say it was not valuable, I said it was less valuable”. Again, his claim needs to be read in the context in which it was made.

Sacrificing truth and rational reflection to fit pre-formed narratives has been a constant feature in this pandemic, which might partly explain why little progress has been made on seriously discussing options like those expressed in the Great Barrington Declaration about shielding vulnerable people while keeping society as open as possible, or making COVID-19 vaccination mandatory. For example, the current trend among academic and intellectual circles is to criticize the Swedish approach (Sweden never locked down and tried to strike a balance between restrictions and protecting the liberties and the economy) and to suggest that it failed miserably. But assuming facts still matter, Sweden has one of the lowest COVID-19 mortality rates in Europe and, very importantly, is one of the least affected economies when it comes to domestic gross product forecast.

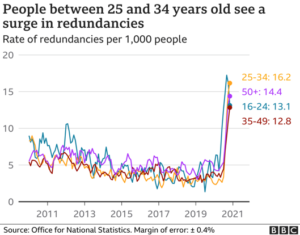

The last aspect is crucial because recessions, like the one we are having in the UK, are historically associated with higher morbidity and mortality and significant deterioration of mental health. This cost will be mostly paid by the young. To give just an idea, 1.72 million people in the UK are currently jobless (that is 5% unemployment), which is the highest figure in over 5 years, and those aged 25 to 34 have the highest risk of redundancies. The table below is pretty eloquent. This is in addition to the educational gaps of children because of school closure, increased levels of serious anxiety and depression during lockdowns reported by parents of school age children (who do belong to the young generations overburdened by restrictions and at low risk of COVID-19), and the exacerbation of various sorts of inequalities among young generations caused by education gaps. Keeping schools and universities closed contributes to these burdens and inequalities.

Reporting these figures, the BBC says that this is the grim situation “as Covid continued to hit the jobs market”. But this frequently used wording is misleading. These are more the result of pandemic measures, and most notably lockdowns, than of COVID-19 itself.

One of the many slogans that has been used to try to accommodate facts to pre-formed narratives has been the idea that there actually is “no trade-off between health and wealth”, or that lockdown, while keeping infection rates down, also benefits the economy. So we should not attribute the economic crisis and unemployment rates to pandemic restrictions. Lockdown looks like a win-win. This is a nice narrative but, as this very precise analysis points out, it only works if lockdown manages to eradicate COVID-19 in the short term, as has happened in some countries such as New Zealand. For most high-income countries, that is not a realistic target and actually, in the long term, there is indeed a trade-off between the impact of lockdown in terms of economic costs – which will have a more significant impact on young generations’ prospects – and its impact in keeping infection rates low – which mainly benefits the elderly.

The elderly benefit more from restrictions because they are at higher risk from COVID-19. It is now well established that COVID-19 predominantly affects and kills old people, who are also way more likely than the young to be hospitalized. The best estimates place the COVID-19 infection/fatality rate (IFR) in high-income countries at 1,15%, but with a very uneven distribution across age groups. For the under 40s, the IFR is lower than 0.1%. Risk of dying doubles approximately every 8 years of age and raises to above 5% in the over 80s. As saw above, risks of ‘long covid’ are also much larger in the elderly and the vulnerable.

Thus, the young are disproportionately affected in terms of education opportunities, job prospects, and expected long term physical and mental health outcomes of lockdowns, and do not benefit significantly from the reduction of infections produced by lockdowns. The elderly benefit disproportionately by the reduction in infections produced by lockdowns because they are at higher risk of significant health consequences from COVID-19, including death, but will not be significantly affected by the implications of lockdown. They will not significantly suffer from unemployment and the long term socioeconomic impact of lockdown.

There must be a threshold after which the sacrifices imposed on the young are simply too large and therefore this uneven distribution of benefits and harms across generations is unfair. There will inevitably be disagreement on where that threshold is and whether we are already past it, but that there is such a threshold at some point is really not disputable.

There are three reasons to think that we are already beyond that threshold and therefore that the imbalance of benefits and harms of lockdown mentioned so far is ageist against the young.

First, as the figures above suggest, the imbalance is at this point very significant and the cost on the worst off has grown very large. This does not necessarily make an imbalance unfair, but is a good indicator.

Second, a factor that makes imbalances or benefits and harms disproportionate or unfair is if the imbalance could be reduced at no significant cost. We should be prepared to pay some small cost to reduce imbalances for them to be fair and ethically justified. Accepting a certain imbalance when it could be reduced at some small cost makes the arrangement unfair. Evidence suggests that the actual benefit of lockdown-like measures compared to alternative forms of restrictions that do not involve stay-at-home orders and business closures is relative small and that “[s]imilar reductions in case growth may be achievable with less restrictive interventions”. It is unfair to simply accept this imbalance of harms and benefits when we haven’t taken this evidence into account and acted accordingly.

Third, imbalances of harms and benefits are unfair when there are reasonably available arrangements whereby those who enjoy the benefits would also take on more of the costs, compared to those who enjoy less benefits. An available arrangement to redistribute costs and benefits in a way that is more fair – that is, whereby those who get most of the benefits also take on more of the costs – while protecting public health systems is a form of selective lockdown, or shielding of the elderly and the vulnerable, as has been suggested early on in the pandemic but never seriously considered (see also the case for it in this document from October 2020).

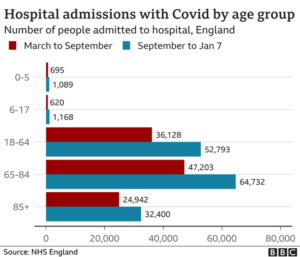

We also need to keep in mind that one of the main reasons, if not the main reason, in support of lockdown is the need to preserve public health systems’ capacity to take on new patients (both COVID-19 and non COVID-19). A system like the NHS is under unprecedented pressure and near capacity. While it is true that with the latest wave and the new COVID-19 variants hospitalisations increased across all age groups (including the young), it is still the case that, as reported by the BBC on 11 January, “the overall pattern of those at risk of becoming seriously ill or dying has not changed significantly”. As of 18 December 2020, hospital admission rates among the over 85s was almost 50 times higher than for those aged between 15 and 44 years, and the hospital admission rate was lowest among children aged between 5 and 14 years, at 0.6 per 100,000 people (ONS 2020). The table below shows the age distribution of hospitalizations in England in the period September 2020-January 2021, which covers the period of the spread of the new “English variant” of the virus. The 65-84 age range is quite large, but a selective lockdown that posed the threshold for shielding measures somewhere in that range, and very plausibly close to 80, would go a very long way in alleviating pressure on the healthcare system.

Thus, selective lockdown would not only be a fairer way of distributing harms and benefits of restrictive measures, but also a solution that would allow healthcare systems to cope with the pressure posed by COVID-19 by reducing infections in the groups more likely to be hospitalized.

The fairest way of achieving the same goal ought to be preferred. This is very unlikely to be lockdown, because lockdown is ageist against the young.

Thanks Alberto Giubilini for this excellent post, which I cannot really find anything to dispute with, except perhaps for this question:

– what reason is there in favor of the assumption — which I think you are making there — that the fairer distribution of costs versus benefits you are recommending won’t be disturbed by a surge of infections when you’re letting the young people commute in and out from home, infecting parents and relatives — whether under lockdown or not?

Thanks. That is largely an empirical issue around how selective lockdown is implemented. Ideally, you want to miminize as much as possible the interactions between the young and the vulnerable, for the limited time necessary to vaccinate the latter group. This would almost inevitably result in a surge of infections among the young, but if those interactions are properly minimized, such surge will not result in a too large increase in deaths and hospitalizations, given the evidence I provide above. Needless to say, this is far from an ideal arrangement. But it is a far from ideal scenario we are dealing with, so we cannot really expect solutions to be costless. The real challenge is to spread costs as fairly as possible. One reason to think that selective lockdown could work is that a surge in infections among the low-risk groups might, as a side effect, speed up herd immunity, so produce an overall benefit for the population. This is not an issue I have really looked into, but you might want to take a look at this by other piece by Bridget Williams, Julian Savulescu and others, posted yesterday on the jme blog. I think these two pieces complement each other: https://blogs.bmj.com/medical-ethics/2021/01/27/the-ethics-of-age-selective-restrictions-for-covid-19-control/

1. “I suggest that current lockdown policies are an unfair form of age-based discrimination against young generations … The costs of lockdown are mostly on young generations … The benefits of lockdown mostly accrue to the elderly”

That’s an implausably broad definition of ageism. Under that definition a lot of things e.g. public funding for soccer practice fields and public playgrounds is unfair ageism, since everyone including the elderly pays for them through taxes yet mostly young people use them.

Does Giubilini think public funding of soccer practice field and public playgrounds is unfairly ageist? If not then the definition of ageism must be revised.

2. ” There are cases of “long covid” among the young, as there are cases of deaths. But these are rare …”

Giublini’s argument claims one group is unfairly treated compared to another group in terms of the net sum of costs and benefits from covid policy.

But then why does not the same type of fairness argument apply between the groups and ? The latter group is the worst off in terms of QALY type quantitative life evaluations since some of those vulnerable young persons would die without lockdown and that would deprive them of their whole, long future life. In comparison non-vulnerable young persons only face, as direct consequences from a lockdown, reduction in level of educational attainment, fewer economic gains, and other such weaker deprivations.

In reply it could be said face similar risks *indirectly*. That’s were Giublini’s “recessions … are historically associated with higher morbidity and mortality and significant deterioration of mental health” comes in. So from a wider perspective it is loss of young lives vs loss of young lives.

But to that we can counter that *if* the argument is allowed to move outside of the more narrow health care prioritization sphere, where we compare direct health impacts from covid for different groups, and also consider indirect effects in the economy and society as a whole then there are also lots of other resources and policy tools up for discussion that might prevent such indirect harmful effects on young people. One key fact here is that the economy as a whole wastes tremendous resources on a lot of other things that are much less important and in no way essential to peoples lives. For example much of the consumption of rich people, and the natural resources and labor required for that consumption to continue, increases their net well-being or QALY only very little if at all. That’s because much consumption by rich people is status oriented, where one rich persons status gain is another rich persons status loss.

Thus if fairness is the lens we use to evaluate policy and if the policy scope should be economy wide then such alternatives must also be on the table in the discussion. Fairness may require keeping lockdowns to protect the worst off vulnerable young and at the same time redirect resources from the rich to protect other young people from indirect harmful effects. Why pit the directly vulnerable young, the indirectly vulnerable young and the vulnerable old against each other when there are more well off and less vulnerable groups who currently consume a lot of economic much more wastefully?

Thanks

About your first point. I agree that the definition as you have framed it is implausible. But that is not the definition I gave. The definition I gave was “”an unfair form of age-based discrimination against young generations.”

The key word is ‘unfair’, and in the end I give the 3 reasons why I think at this point it is unfair, i.e. ageist. The first reason seems to address most of your objections: the imbalance is very large (I don’t say that this is a sufficient condition of course) and at this point disproportionate. Your examples such as the playground one are not like this, also because playground and football pitches are funded by everyone, young and old (so it is not analogous to lockdown even in this respect, since lockdown’s burdens are mostly on the young)

I am instead broadly in agreement with your second point: a fairer distribution of resources would mitigate some of the negative effects of lockdown. But I think that that could, at best, move that threshold I mention (when I say “There must be a threshold after which the sacrifices imposed on the young are simply too large and therefore this uneven distribution of benefits and harms across generations is unfair”) a bit further up. How significant a difference it would make is, again, largely an empirical matter, as there is only so much wealth that you can feasibly move around. In the UK we are almost 1 year into the pandemic and had 3 lockdowns. Lockdown is becoming a long term strategy instead of a temporary emergency fix. I am very skeptical that fairer distribution of resources would at this point make a significant difference to the harms lockdown has already caused and is causing. But I might be wrong on this. Part of the problem I think is that, while there is (rightly) a lot of research on the impact of the virus, there is not enough reserch, in my view, on the impact of lockdown and on the effect of mitigation strategies.

“the definition as you have framed it is implausible. But that is not the definition I gave. … I give the 3 reasons why I think at this point it is unfair”

Ok, I see now that my first point was sloppy and incorrect. I retract it.

But there is still something strange to me with your ageism claims. Something can be unfair between some/many/most/all individuals from two age cohorts without being ageist. My intuition is that ageism requires more. One clear form of ageism would be if a policy is based on prejudices about one age group. For instance “young people are stupid and therefore we should prohibit people from voting until 30 years old” is ageist. The lockdowns aren’t ageist in that way. There could be other forms of ageism, but I don’t think your 3 reasons are sufficient to establish anything that intuitively fits the label ageism in my mind. I suppose one thing holding me back here is that you give no general account of what is and isn’t ageism. If you could show some other examples that most would already agree are ageist and then show how your 3 reasons fits well with those cases then that would bolster your use of the 3 reasons in this case of covid and lockdowns.

I also doubt that your three reasons are sufficient to establish unfairness.

“First, as the figures above suggest, the imbalance is at this point very significant and the cost on the worst off has grown very large.”

A trouble with that claim is those young people who are vulnerable to be killed by covid. They’re the truly worst off. Then there are also some old people in good health who are run a smaller risk from covid than some younger people. This shows that the groups of young/old people, and effects from policy on them, isn’t as homogenous as your argument seems to require them to be. That makes it hard to draw any general conclusions about convid policy fairness/unfairness between the young/old as a group, especially when the policies in question does not formally discriminate based on age. The lockdowns apply for everyone, regardless of age.

“Second, a factor that makes imbalances or benefits and harms disproportionate or unfair is if the imbalance could be reduced at no significant cost.”

I don’t think that is a condition for if something is unfair or not. Something can be unfair even if it would be very costly or even impossible to remedy it. Some imbalances that are inexpensive to remedy might still not be unfair.

“Third, imbalances of harms and benefits are unfair when there are reasonably available arrangements whereby those who enjoy the benefits would also take on more of the costs, compared to those who enjoy less benefits.”

How is that different from the second reason? It looks to me like the same claim reworded.

“I am very skeptical that fairer distribution of resources would at this point make a significant difference to the harms lockdown has already caused and is causing.”

We are very far from each other in background assumptions then because my intuition is that implementing a universal basic income would remove and even reverse all negative health effects currently associated with unemployment. Negative health effects are only caused by precariousness, stigma and lack of money for basic needs.

ok I suppose there are different plausible understandings of what counts as ageism, much like the case of other -isms. Yours is certainly one, based on some form of negative prejudice. Another one is simply one that discounts the harms to certain groups, regardless of whether these harms or the discounting are connected to some form of negative prejudice.

We use the same criterion with other more widely discussed -isms after all, such as racism or sexism. E.g. male doctors who refuse to perform abortions are often accused of being sexist against women, although the refusal is more likely motivated by personal religious beliefs about foetuses than on prejudices on, say, women’s role in society. The reason why they are considered sexist is that this attitude poses great burdens and risks on women and these doctors simply don’t care enough, giving priority to their own perceived moral purity. Or affirmative action is often labelled as a form of ‘reverse racism’ or ‘reverse sexism’, but it does not necessarily express some prejudice against the group being penalised. We might debate around the justification of these behaviours and actions, of course, but if your point is around language, those seems to be meaningful uses of the term, even if they do not necessarily reflect some negative prejudice towards the targeted group (e.g., one could say that affirmative action is an unfair form of discrimination against certain groups, so a form of -ism, and there could stil be an open question on whether it is motivated (or even ethically justified) by some other principle, rather than by some prejudice agains the penalised group). The same with lockdown. The young are disproportionately burdened, and we do not care enough (at least that was my argument). It’s not that there necessarily is some prejudice against the young, but it is still a form of ageism for these reasons: the interest of a group are not given enough consideration compared to the interests of another group, and the fact that there are alternative ways to give the former more considerations that come at little cost is a strong indicator of this.

But in any case, even if one does not agree with what I have said so far and we stick with your definition of ageism based on prejudice, it is not clear to me that discounting the burdens on the young does not conceal some form of prejudice about the ethical weight of their interests. One prejudice might simply be the idea the the young owe something to the elderly simply in virtue of being young, which I think is wrong. The problem is that when it comes to assessing prejudices, as is often the case with all kinds of -isms, there is always a great deal of opacity (how can you reliably tell , outside some sophisticated experimental psychology context, if someone is actually prejudiced against someone else?)

You are right that all this would require a preliminary philosophical discussion around what counts as ageism. The definition I have given seems plausible and consistent with the use of other -ism terminology to me. But if someone is not convinced by it, I am happy to say that lockdown is simply unfair discrimination against the young without saying that it is ageist. This changes the terminology but not the substance, as far as I can tell .

But my understanding of ageism I think should address your concern about the 3 reasons not being sufficient. They are probably not sufficient if we take your definition of ageism, but they probably are (as I see it) if we take mine. (on your point: the second and third condition are different in that the second is about the overall cost on society, the third is about the distribution of the costs. The might practically overlap but are conceptually distinct, as I see it).

As for your suggestion of a universal basic income as a possible solution to the problem, that would require some more philosophical discussion. I don’t really have a view on it, I can see pros and cons. But my point in the comment above was that “there is only so much wealth that you can feasibly move around”. I don’t see the introduction of universal basic income in the middle of a pandemic as a very feasible option. But I might be wrong.

Thanks, that cleared up some things for me. I agree with you that people can use sexism/racism in different senses and one recognizable and thin such sense does not require any overt prejudice so I accept your point that ageism could also be used in such a thin sense. The senses are important to distinguish though so my initial confusion and your clarification can now be of help to others reading this, which is good.

I also think you make a good point that it might be the case some underlying anti-young prejudice unintentionally shapes some of the policy makers actions. I’m open to that possibility, though I’m also no less open to the reverse possibility i.e. unintential anti-old bias.

“I am happy to say that lockdown is simply unfair discrimination against the young without saying that it is ageist. This changes the terminology but not the substance, as far as I can tell .”

Ok, I’ll keep my focus only on the unfairness charge from here on out and set the ageism terminology stuff aside.

“But my understanding of ageism I think should address your concern about the 3 reasons not being sufficient. They are probably not sufficient if we take your definition of ageism, but they probably are (as I see it) if we take mine.”

I’m afraid I disagree on the last part here, because my objections to the 3 reasons in my previous post were meant as objections to them merely as grounds for establishing unfair discrimination. That’s everything I wrote after the sentence “I also doubt that your three reasons are sufficient to establish unfairness”.

“the second and third condition are different in that the second is about the overall cost on society, the third is about the distribution of the costs.”

Thanks, that does differentiate them. But then I would stick to my stated objection against condition 2 until it is countered. I would also add an objection against condition 3, namely that 3 in my mind is no condition for if something is unfair or not. 3 seem instead to be something that may make a moral difference downstream from that. With downstream I mean a later point in deliberation when we already, on other grounds, have established if something is unfair or not and thereafter are considering what if anything should be done about it and how unfairness remedial actions should be weighted against other important policy goals that we also have moral reasons to pursue.

However the one objection that has by far the strongest intuitive pull on me is the one about some vulnerable young people being the very worst off. I think it challenges the whole young vs old fairness framing going on here.

“I don’t see the introduction of universal basic income in the middle of a pandemic as a very feasible option.”

I do, so that’s a very big difference in our priors here. I would categorize some covid relief payments in the US and other places to be quasi-UBI payments, although temporary. They’ve been very popular. Another data point regarding popular support in several european countries is in the fresh survey reported on here https://basicincome.org/news/2021/01/europeans-get-it-basic-income-strengthens-resilience/

yes sorry, I worded it poorly. What I meant is that my discussion of what I consider ageist brings up what I take to be the unfairness in lockdown policies (whether or not we call it ‘ageist’). And this is the 3 conditions above about the disproportionate distribution of costs and the alternatives available to minimize the overall costs and redistribute them such that those who get more benefits also carry more of the costs (disregarding these alternatives means that we do not care enough about the interests of the young , which is part of the unfairness (or ageism) in question).

As for the second condition, the condition was ” Second, a factor that makes imbalances or benefits and harms disproportionate or unfair is if the imbalance could be reduced at no significant cost”

Your objection to it is “I don’t think that is a condition for if something is unfair or not. Something can be unfair even if it would be very costly or even impossible to remedy it. Some imbalances that are inexpensive to remedy might still not be unfair”

My condition was about ‘a factor’. It was not meant to be sufficient condition. But I think it is necessary (so I don’t think that something that would be extremely difficult or impossible to redress can be considered ‘unfair’ – or maybe it can be only metaphorically). That is where the 3rd reason becomes relevant: the imbalance is not only addressable at little cost (which as you say might not be enough to make it unfair), but in such a way that the costs are borne in greater proportion by those who benefit more from the measures (selective lockdown and protection against covid). This was the third reason. (I accept the three reasons together might still not be sufficient).

I think the kind of unfairness as created by those 3 reasons can be seen if one thinks of a very extreme version of the current scenario: suppose a full blown lockdown with e.g. school closure that goes on 10 years and a situation where, perhaps thanks to vaccines, COVID-19 only kills a small number of people older than 100 (e.g. maybe because they do not respond too well to the vaccines). I think the vast majority of people would agree that this is beyond that fairness threshold. But it would be unfair precisely for the 3 reasons I mention, as far as I can see.

The current scenario is not that extreme of course. But it is still the case, as I say, that there must be a threshold. So we would disagree on whether we are past it yet, which was one of the central points of my arguments (possible disagreement on where the threshold is). But it does not undermine the validity of the 3 reasons, but just their applicability to the current scenario.

On universal basic income: if you consider relief payments (or perhaps the furlough scheme in the UK?) as a form of quasi-UBI, I agree those substantially mitigate the unfairness of this policy. But that they completely address it, I am not sure. Actually, they might even exacerbate it. The millions and millions or $ and £ currently thrown at these schemes will have to be repaid somehow at some point. And again, it will be the young who will have to pay them. But I don’t really know about UBI, it’s not something I have given much thought, so there might very well be some aspect of it that I am missing.

“We are very far from each other in background assumptions then because my intuition is that implementing a universal basic income would remove and even reverse all negative health effects currently associated with unemployment. Negative health effects are only caused by precariousness, stigma and lack of money for basic needs.”

This position is not supported by psychological research. Psychological research consistently shows that unemployment is one of the worst things you can do for a person’s happiness. The effect of unemployment on happiness/wellbeing is, according to some studies, similar in size to that of bereavement (and potentially greater than bereavement of loved ones that are not the closest to you). Furthermore, simply replacing a person’s lost income with an equivalent amount does not erase the effect of unemployment on happiness. It mitigates it, but the effect of unemployment in producing unhappiness is great even once income is replaced. So universal basic income would not remove and reverse all negative health effects – the mental health effect would still be significant.

“Negative health effects are only caused by precariousness, stigma and lack of money for basic needs.”

Furthermore, there is also very consistent research showing that social isolation is, in and of itself, terrible for mental and physical health. Social isolation is at the heart of lockdowns and social distancing policies – they only work if they keep us isolated.

Obviously, for those who would die of COVID, the effect of COVID on health will be greater than that of social isolation. But for the vast majority who would survive a COVID infection and not end up with long COVID, social isolation and poverty will be the greatest threat to their health. Furthermore, even those who are protected from dying are likely suffering horribly under lockdown policies..

Thanks Kookoo. These are all objections to Dront’s points, not to my points, as far as I can see. I am myself very unsure about UBI, but as I said I don’t know much about it. I would be interested though in how Dront replies to your comments.

(The comment form ate some formatted strings in the previous comments. Here is a retry with new formatting.)

1. “I suggest that current lockdown policies are an unfair form of age-based discrimination against young generations … The costs of lockdown are mostly on young generations … The benefits of lockdown mostly accrue to the elderly”

That’s an implausably broad definition of ageism. Under that definition a lot of things e.g. public funding for soccer practice fields and public playgrounds is unfair ageism, since everyone including the elderly pays for them through taxes yet mostly young people use them.

Does Giubilini think public funding of soccer practice field and public playgrounds is unfairly ageist? If not then the definition of ageism must be revised.

2. ” There are cases of “long covid” among the young, as there are cases of deaths. But these are rare …”

Giublini’s argument claims one group [young people] is unfairly treated compared to another group [old people] in terms of the net sum of costs and benefits from covid policy.

But then why does not the same type of fairness argument apply between the groups [young people who do not risk dying of covid] and [young people who do risk dying of covid]? The latter group is the worst off in terms of QALY type quantitative life evaluations since some of those vulnerable young persons would die without lockdown and that would deprive them of their whole, long future life. In comparison non-vulnerable young persons only face, as direct consequences from a lockdown, reduction in level of educational attainment, fewer economic gains, and other such weaker deprivations.

In reply it could be said the group [young people who do not risk dying of covid] face similar risks *indirectly*. That’s were Giublini’s “recessions … are historically associated with higher morbidity and mortality and significant deterioration of mental health” comes in. So from a wider perspective it is loss of young lives vs loss of young lives.

But to that we can counter that *if* the argument is allowed to move outside of the more narrow health care prioritization sphere, where we compare direct health impacts from covid for different groups, and also consider indirect effects in the economy and society as a whole then there are also lots of other resources and policy tools up for discussion that might prevent such indirect harmful effects on young people. One key fact here is that the economy as a whole wastes tremendous resources on a lot of other things that are much less important and in no way essential to peoples lives. For example much of the consumption of rich people, and the natural resources and labor required for that consumption to continue, increases their net well-being or QALY only very little if at all. That’s because much consumption by rich people is status oriented, where one rich persons status gain is another rich persons status loss.

Thus if fairness is the lens we use to evaluate policy and if the policy scope should be economy wide then such alternatives must also be on the table in the discussion. Fairness may require keeping lockdowns to protect the worst off vulnerable young and at the same time redirect resources from the rich to protect other young people from indirect harmful effects. Why pit the directly vulnerable young, the indirectly vulnerable young and the vulnerable old against each other when there are more well off and less vulnerable groups who currently consume a lot of economic much more wastefully?

thanks, I have replied above

Alberto,

Thank you for your interesting post. I believe you have framed convincingly that even if lockdowns were proven to be beneficial to some portion of the population, there would still be issues regarding whether they are unjust to some other portion of the population.

It can be discussed whether your arguments against blanket restrictions across the board and in favour or more focused approaches are convincing enough, but I think that it is beyond dispute that restrictions imposed on people that have the least risk from the disease, but bear the higher costs of the restrictions are unfair. It is almost the definition of unfair. Another totally different issue is whether such unfairness demands any sort of reparation. That is again subject to discussion.

I hope nobody would argue that, given than blanket lockdowns are unfair, an alternative intervention that imposed less unfair costs, while retaining the benefits, would be preferable.

But that is not what I want to argue. In my opinion, the real issue about lockdowns (and other forms of forced social distancing) is that they are stupid. Not only they do not provide any benefit to the people more at risk, they are actually harmful to these very people. This was supposedly known to everybody involved in Public Health until 2020 and it is a direct consequence of the dynamics of infectious diseases.

Under the deranged new view of pandemic response, much is said about the role of infected people spreading the disease to other people, but it is not considered the role of recovered people shielding the disease from other people. Thus, a more rational view of how to cope with a pandemic that is already prevalent is to protect yourself if you are at risk so that other people, who have less risk and protect themselves less, get infected sooner and recover. What you don’t want if you are a vulnerable person is that these people that have less risk than you also protect themselves, because then your risk of getting infected and die increases.

The beauty of the rational way is that precisely the people who have the less risk will tend to expose more to the disease, so society as a whole maximises the benefit and minimises the risk.

Instead, what we have seen is that the vulnerable have increased their exposure to the disease with respect to the less vulnerable, increasing the direct death toll of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Good work!

So, to summarise, not only generic lockdowns are unfair to the young, they are also lethal to the older.

That’s all great, I applaud it. Most especially “Sacrificing truth and rational reflection to fit pre-formed narratives has been a constant feature in this pandemic”, lovely to see such an eloquent and intelligent person expressing this entirely accurate view.

On the other hand, the premise seems to be that lockdowns work. Apart from pre-endemic lockdowns (nz, aus, vnm, etc), which still may not “work” over the long run when / if freedom of movement is restored, that is far from on a solid evidence base.

At which point we default back to 2019 logic / THE EVIDENCE BASE, where you don’t quarantine the healthy, you do isolate the sick and you do shield the vulnerable. Making the above analysis, whilst beautiful, moot.

That’s all great, I applaud it. Most especially “Sacrificing truth and rational reflection to fit pre-formed narratives has been a constant feature in this pandemic”, lovely to see such an eloquent and intelligent person expressing this entirely accurate view.

On the other hand, the premise seems to be that lockdowns work. Apart from pre-endemic lockdowns (nz, aus, venture ), which still may not “work” over the long run when movement is restored, that is far from on a solid evidence base.

At which point we default back to 2019 logic / THE EVIDENCE BASE, where you don’t quarantine the healthy, you do isolate the sick and you do shield the vulnerable. Making the above analysis, whilst beautiful, moot.

Exactly.

We can debate fairness. But the reality is that no one has shown that lock downs and so forth work. Efficacy is unproven.

I believe too that there are many elements of this disease that we do not understand.

NZ apparently shows the benefit of lock down and border controls. The whole of Oceania has low mortality though. There may simply be factors at work that we do not understand related to geography, seasonality and so forth.

Humans do like to think that they can control things. We resemble far more the Aztecs, making a human sacrifice each day to ensure that the sun rises, rather than the scientific rationalists that we think we are.

Now we think that vaccines are the Holy Grail.

This is a mad and evil period in humanity.

Mass hysteria. Like the Salem witch trials, all are foaming at the mouth about “protecting the vulnerable”.

As one of those, having been tortured as a child, held in isolation, with no one protecting me from a “parent” [female], I RESENT being imprisoned AGAIN.

It is TERRORISM, nothing else. It is high time people rose up and started fighting back.

Dear Alberto,

Very well written article. As a university student during these times, I feel that university students get criticism in both ways – for being perceived to not follow lockdown rules as well as other health groups because they are the least likely to suffer problems from it, as well as not being grateful that they are lucky that they are in the category. I can accurately inform you that most university students feel quite miserable.

I think that the concept of the threshold is right, but all 3 of your claims rely on empirical research. No such conclusive research exists either way (by conclusive I mean laws of gravity type stuff.) Academic consensus from professional epidemiologists seems to favour lockdowns, but this is not unanimous and therefore indicates reasonable doubt. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v341VNPgL50

Even the ideas you float are subject to empirical doubt – does the nature of lockdown mean that there will there be a miracle recovery for the economy? Who knows. Also note that there are exponential effects – there is probably a point of no return for the healthcare system where people can no longer be treated for routine problems (strokes, heart attacks) which are avoidable deaths if there are too many people in the hospitals with COVID. Given uncertainty about where this threshold lies, it seems prudent to play it “safe”, but of course this just feeds into your argument about whether lockdowns do actually work. But the more general point is that given that we know that the adverse consequences from the healthcare system are not linear and we do not know whether the economy, mental health, education, physical health etc, have similar non-linear adverse consequences, it makes sense to play it safe with regard to the health system in the face of a lack of empirical research.

Given the existence of reasonable doubt, and also the requirement of multi-disciplinary research that does not exist, this indicates that there needs to be public justification for decisions made, rather than a stifling of opposing views. There can be reasonable disagreement about what the threshold should be, regardless of the empirical research to suggest where we are in regard to this. Lord Sumption’s quote seeks to underline this idea. That means that there is a possibility for governments across the world to try to convince the public that they are right to lockdown, which the UK government has not done particularly well. Ageism seems to be one defeasible reason why lockdowns might take us over this threshold, but it is not decisive.

You are right. But politicians and media mavens scrupulously avoid knowledge of this

Comments are closed.