Written by Edmond Awad

In the popular series “Game of Thrones” (and the corresponding “A Song of Ice and Fire” novels), the “Game of Faces” is a training method used by the Faceless Men, an enigmatic guild of assassins. This method teaches trainees to convincingly adopt the face of others for their covert missions.

The Game of Faces can be seen as a metaphor for the way we interact with others in the real world, as well as the way we present ourselves online. In the Game of Thrones TV series, the Faceless Men are able to change their appearance at will, which allows them to deceive others and get close to their targets. This ability can be seen as a symbol of the power of deception and manipulation.

In the real world, we are not able to change our appearance at will, but we can still use our appearance to manipulate others. For example, we might dress in a certain way to make a good impression at a job interview, or use makeup to look more attractive. We can also create false personas online.

Throughout history, the importance of how we present ourselves to others has grown in two ways. Firstly, the average number of new interactions with strangers has increased. Secondly, people are more likely to initiate interactions based on first impressions. For example, the shift from small-scale societies to larger, more complex ones led to a change in human interaction. In small communities, in-depth knowledge about each others’ family, friends, and reputation in the community created a strong foundation of mutual trust. As societies expanded, interpersonal familiarity diminished, and people began to rely more on social institutions and heuristics (including appearance) to develop and maintain interactions. Reliance on appearance might not have been the only or even the most significant factor, but it likely played a role in how people navigated interactions with strangers in an increasingly complex social landscape.

In the age of the internet, our faces have gone digital, and the way we present ourselves to others has become even more important. Social media platforms are filled with carefully curated profile pictures, each telling a story about who we are or who we aspire to be. Our digital faces have become our calling cards, and the art of crafting these images is now an integral part of our social lives. Filters, poses, backgrounds – all are chosen with intention, shaping our online identity.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has entered this arena as both a tool and a player. Initially, AI helped us refine and enhance our digital personas. We’ve seen apps that allow us to experiment with different looks, optimise our images for virality, or even generate entirely new faces. But AI is not just assisting us; it’s learning from us and starting to play the game itself.

The ethical implications of AI’s role in the modern ‘game of faces’ are numerous and multifaceted. For one, the use of AI to craft and manipulate faces can blur the lines between authenticity and artifice. While humans have always engaged in self-presentation and even deception, the scale and sophistication that AI brings to the table introduces a new level of complexity, perhaps comparable to the Faceless Men in Game of Thrones. Does this superior ability of changing faces much more skillfully and at will is what makes it problematic? Suppose we limit its performance to human-level, is there still something more problematic about being deceived by machines compared to by humans? Or is it because an AI-generated face does not carry the same meaning and intention as a human-crafted one?

On a broader societal level, AI’s entry into the ‘game of faces’ might also influence our trust in digital interactions. If we know that behind any face there might be an AI, does it reduce our trust in online communities? Does it make our digital connections shallower or even more superficial? The game of faces becomes not just an individual pursuit but a collective challenge, requiring new ways of thinking about responsibility, trust, and human-machine coexistence.

The entrance of AI into the game of faces isn’t just a technological advancement; it’s a turning point that requires us to reconsider how we understand ourselves and others in an increasingly complex digital landscape. It demands a critical examination of our ethical principles, our concepts of identity, and our social interactions in an age where machines are not just tools but active participants in our lives.

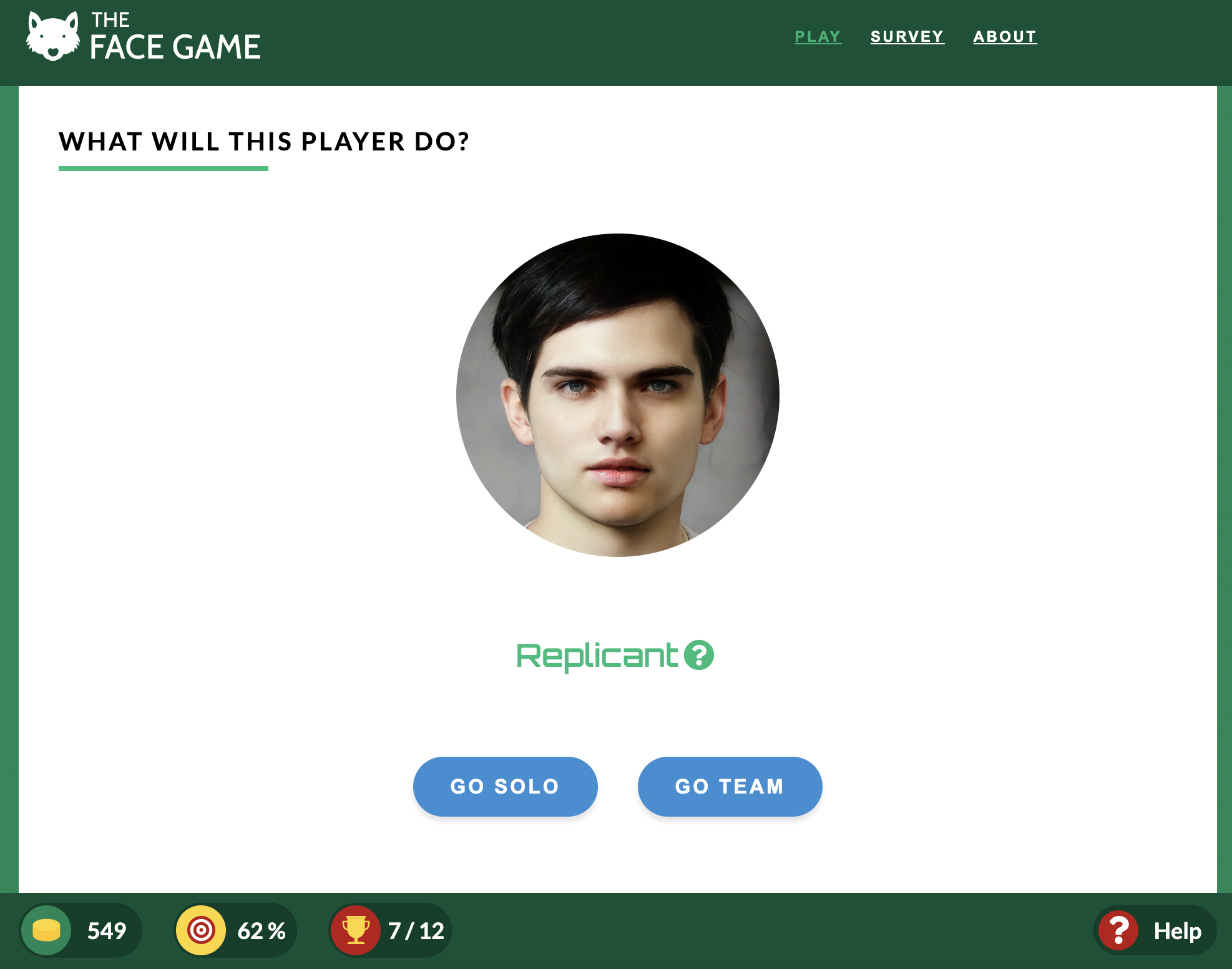

This leads us to “The Face Game” (https://the-face-game.net), a project that I am proud to be a part of, which is being carried out by a large team from various institutions. It is a space where humans and AI interact, exploring how AI might choose its face depending on its objectives. As a player in this game, you interact with other players (humans and AI) based on their profile picture. Similarly, if you upload your own profile picture, you will see how other players interact with you based on it. You can also learn about the project here (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EyD-CWllu1E).

Our digital faces are our modern masks, reflecting not just who we are but who we want to be. As technology continues to advance, and as AI becomes more integrated into our lives, understanding this game of faces becomes not just a philosophical inquiry but a practical ethical consideration. ‘The Face Game’ opens the door to these complex questions, offering a glimpse into the future of our digital identities.

🙂 Excellent Article, Excellent Blog , Excellent Site ✅✅✅

A favored acquaintance of mine calls his blog, the double look. I think he is a Frenchman, Monsieur JeanPierre, and, I enjoy our often-contentious, yet ever-good-natured exchanges…well, I like to think so. There are double looks;second looks, and, looks that alternate between one another: the duck-rabbit; old crone-young ingenue; shifting cube; which-line-is-shorter;and so on. All of these are perceptual, and, when our perception changes—as it will—the duck appears as rabbit; the crone transforms into iingenue; the cube shifts, while the line with inverted arrows always looks longer. Now, I don’t know if any of this changes when a subject is under the influence of a hallucinogen. Am I sure what THAT means? No. I don’t know how, or if, any of this might affect AI. Why? AI lacks both perspective and perception, seems to me. The perceptual shifts, in particular, seem eternally foreign to to machine learning. The circuits just aren’t there. How would we know an AI device was under the influence of a hallucinogen? Sorry. Don’t think so. There are many problems and questions here. Don’t cha think?

I looked at the representation of a face, first thinking: this looks like Tom Cruise. Of course, that was not the point, or the intention, was it? Then, I tried to see more deeply into the representation. Difficult. The face is flat, lifeless. Implacable. Now, we are getting somewhere, I thought. Lifelessness is at the

core of articiciality, getting to the bottom of things. Tom would be insulted, or perhaps, amused? Finally, though I fancy myself creative and imaginative, I just don’t know the intention(s) of this game. The archaic perceptual shifts I mentioned in my previous comment are classical representations of LeGros’ double look. Or, are they? None of this face stuff means much to AI, seems to me, for reasons articulated here and elsewhere. You cannot embed consciousness into an amoeba. Nor, can you teach it anything about fine art—whatever you think that may be. AI is that, and only that. It is not alive. Not should it ever be considered so.

On another blog, where LLMs, AI and such are the hot ticket now, I asked: Is AI capable of scepticism and doubt? Got one reply, so far. It did not offer an answer that was of any use. If the reply had been: I don’t know, that would have told me something. Guess I will wait for someone else to log an opinion.

Comments are closed.