EACME Conference 2025

Healthcare innovation and research often prioritise acceleration and efficiency. This keynote (12th September 2025) challenged this paradigm by drawing on preliminary findings from Project Lazy, which explores judgements about laziness through research and community engagement. The talk had four parts: an introduction to Project Lazy, findings from the philosophical part, findings from the community engagement part, and the connection between these findings and the conference theme.

Part One. The talk began with a puzzling observation: many highly successful, productive people consider themselves lazy or have been labelled as such. Interactive polling revealed that the hard-working academics at EACME too had been affected by laziness judgements, worrying about being lazy or working harder to avoid the label. This revealed something important about how the laziness concept operates in our society: as a criticism, as something that involves a personal or moral failure, something one can be blameworthy for. That’s why laziness judgements can have serious consequences.

They can harm wellbeing in various ways. If someone thinks they’re just lazy whilst in fact they have ADHD, they may not find their way to appropriate support. They can cause anxiety and stress when people can’t meet productivity expectations, or lower self-esteem, leading people to overwork to avoid the lazy label and ultimately burn out. Laziness judgements enable discrimination. Research has shown, for example, that people living with obesity face promotion barriers due to perceived laziness. They deepen social inequalities because harms from laziness attributions are distributed unequally across social groups, disproportionately affecting those with chronic health conditions, neurodivergent individuals, those experiencing homelessness or unemployment, and racial or ethnic minorities. If you’re a white child struggling in school, you’re more likely to get support. If you’re a Black child struggling, you’re more likely to be seen as lazy and receive punitive measures rather than help.

Project Lazy aims to address these issues by clarifying what laziness actually is and challenging harmful assumptions about productivity. It involves conceptual research using methods from philosophy and empirical research using methods from moral psychology. The academic research is shaped and informed by an interdisciplinary academic network and community engagement.

Part Two. Preliminary findings of the philosophical strand of Project Lazy suggested that we should distinguish between true laziness and what I’ve called ‘justified effort management’. Often what appears as laziness is actually strategic allocation of limited internal resources (such as energy and motivation) towards valuable ends. Consider John von Neumann’s habit of abandoning difficult scientific problems for easier ones. He could have tried harder on each problem, but that doesn’t imply he was doing his work lazily. If he reasonably thought that quickly moving on would maximise his overall scientific contribution, his approach was justified. What truly matters isn’t how hard you try, but whether your efforts can be reasonably expected to achieve what is important, what is of value, whilst recognising that effort is a limited resource. Stephen Fry is interesting because he admits he works very hard, yet still believes he’s lazy. He thinks his effort wasn’t directed at the right goal. Given his capacities and talents, he could have achieved things of more value. These, and other cases involving laziness judgements, suggested that laziness can involve unjustified effort avoidance in achieving one’s goal, or in achieving a sufficiently valuable goal.

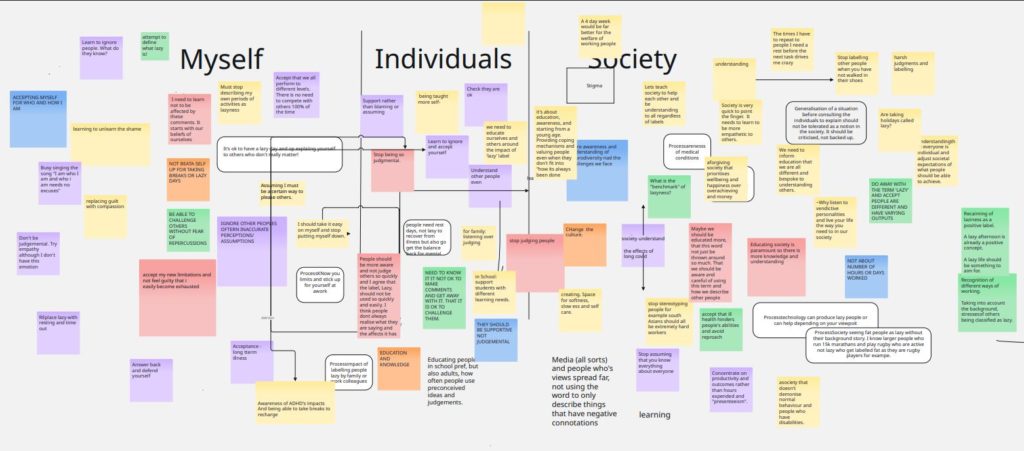

Part Three. Project Lazy includes community engagement to bring in voices of those most affected by laziness labels, though recruitment proved challenging and time-consuming. When asked what needs to change, participants in an exploratory workshop consistently emphasised structural solutions rather than individual ones. They wanted support rather than blaming, acceptance that people are different, and cultural change around productivity expectations. Their views inspired the remainder of the talk.

Part Four. The connection to healthcare ethics became clear when recognising that judgements about laziness often reflect assumptions about what it means to be productive, but what counts as productivity is contested. In academia and healthcare, we currently measure productivity mainly through publications, quick results, and measurable outputs. Community engagement and ethical deliberation are increasingly valued, but often only when they produce rapid, quantifiable impact.

But meaningful engagement takes time. It doesn’t always result in publications or metrics we can easily measure. Think about the researcher who spends months building relationships with communities, preventing potential trial failures down the line. Or the ethicist who takes time for deep reflection and catches problems early. The committee member who slows down rushed ethical reviews. These contributions take time and might appear unproductive by conventional metrics (or might prevent outputs currently considered as productive). But just as the talk showed that apparent laziness is often justified effort management, these seemingly unproductive activities might represent some of our most valuable contributions.

Of course, slowness doesn’t always create value, and the challenge is to determine when it does. Just as the talk distinguished true laziness from justified effort management, we can ask: when is community engagement (as one example of slowing down) justified effort management? If you’re engaging communities because you have good reasons to believe their input will improve your research or serve another valuable goal, your slowing down is justified effort management. If you’re doing it to tick a box on a grant application, that might be unjustified effort avoidance, avoiding the harder work of meaningful engagement.

But we need realistic expectations. Should all already-stretched academics add community engagement to their load? As participants of our Project Lazy workshop noted, everyone is different. This is true in academia too. Not everyone has the skills or interests for community engagement, and that’s fine. It wouldn’t be wise to use their effort this way when they could be more productive in other ways. That would amount to an unjustified waste of effort. We shouldn’t turn community engagement into something people are just expected to do, as this would defeat the purpose entirely.

Our laziness workshop participants called for support, not blame. Academics doing slow work that can be expected to create value may need support too. How this support should be provided is a difficult question. Should academics wanting to do community engagement receive grants to outsource patient and public involvement to specialised companies? Should they be encouraged to use AI to take over certain aspects of engagement, and if so, how? Should we find better ways to reward slow work, for example by rewarding prevented problems? (But how do we determine a problem has been prevented?) These questions remained open, but the framework of distinguishing justified effort management from unjustified effort avoidance may help us think through them more carefully. The talk ended with an encouragement to look differently at those who seem lazy. Maybe they’re recovering from illness. Maybe they’re an exhausted parent finally getting a moment of rest. Maybe they’re taking necessary downtime to avoid burnout. We often don’t know, so we shouldn’t be too quick to judge.

This keynote was delivered by Prof Katrien Devolder (Professor of Applied Ethics, Uehiro Oxford Institute) at the 2025 EACME Conference which took place in Zurich on 12 Sept 2025.