Coming to a mini-mart near you. The FDA has just approved nine very grisly looking warning labels—to be slapped on cigarette packs throughout the USA. But will they work to cut smoking … or will they backfire?

Here are some of the top reasons why these labels may not only fail to achieve the FDA’s desired outcome, but could actually do the opposite – leading to more smoking, not less.

Reactance. This is a technical term in psychology based on the notion that people don’t like being told what to do, what to feel, or how to think. Our good friends at Wikipedia explain the idea this way:

Reactance is an emotional reaction in direct contradiction to rules or regulations that threaten or eliminate specific behavioral freedoms. Reactance can occur when someone is heavily pressured to accept a certain view or attitude. Reactance can cause the person to adopt or strengthen a view or attitude that is contrary to what was intended, and also increases resistance to persuasion.

You probably see where I’m going with this. Considering that these new labels could not possibly be more heavy-handed—coupled with the fact that reactance is one of the most well-validated concepts in all of psychology—my hunch is that a lot of smokers will dig in their heels and light up just to spite. And if the “resistance to persuasion” part is right, it’ll be even harder to change their attitudes down the road. In fact, research has already linked reactance directly to smoking. Claude Miller, for example, has shown that it’s one of the major risk factors for teenagers starting up the practice in the first place.

Wear-out. According to the LA Times, FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg has “emphasized that the FDA would continue to study the effects the images have on the public, and would probably update them yearly in an effort to keep them and their message fresh in consumers’ minds. Outside experts said the government would have to vary the messages to avoid what psychologists call wear out.”

How exactly might they update the images year to year? Make them even more disgusting and gruesome? If so, reactance theory predicts ever-increasing backfiring, with smokers becoming more and more irritated by the in-your-face warnings, more and more likely to assert their agency and freedom by doing the opposite of what they’re told, and more and more resistant to changing their minds. So you’d have an arms race between ramped up shock-and-awe on the part of the FDA, and ramped up reactance on the part of smokers. Is that really going to solve the problem?

Fun thought: Maybe they’ll vary the images along some other dimension. Maybe they’ll go 3-D or holographic. Or maybe they’ll install a singing-telegram computer chip that warbles out an anti-smoking jingle every time you reach for your pack!

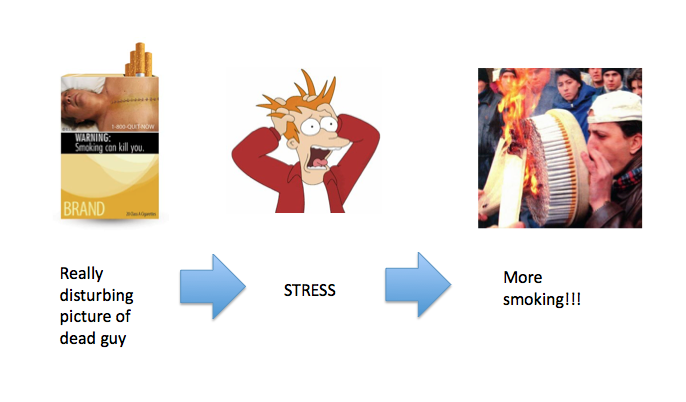

Pop quiz. What do smokers do when they’re stressed out, upset, irritated, annoyed, or otherwise ruffled or disturbed? They smoke. Smokers know this, people who know smokers know this, and in case you weren’t convinced, there’s a lot of research to prove it. There’s also a lot of research showing that when people are exposed to really gruesome or disgusting images, it kind of stresses them out. Put these two pieces together and you get one more reason why the warning labels will probably backfire. Here is a diagram I made:

Any cue will do. On a related note, I recently presented some research on a very similar topic to the British Psychological Society annual meeting in Glasgow. My colleagues and I were investigating some ironic effects that can occur when the brain has to process a negation—like the “no” in “no-smoking” signs. We found that passive exposure to these signs—of the sort that might happen while walking down the street—actually increased craving for cigarettes in smokers, even when they didn’t consciously notice the signs. Their brains dropped the negation and activated “smoking” instead, just like what happens when I tell you “don’t think of a pink elephant.” Sure, I said not to do it, but I got you thinking about a pink elephant just the same, didn’t I?

Any cue will do. On a related note, I recently presented some research on a very similar topic to the British Psychological Society annual meeting in Glasgow. My colleagues and I were investigating some ironic effects that can occur when the brain has to process a negation—like the “no” in “no-smoking” signs. We found that passive exposure to these signs—of the sort that might happen while walking down the street—actually increased craving for cigarettes in smokers, even when they didn’t consciously notice the signs. Their brains dropped the negation and activated “smoking” instead, just like what happens when I tell you “don’t think of a pink elephant.” Sure, I said not to do it, but I got you thinking about a pink elephant just the same, didn’t I?

Policy thought: Plastering cities full of smokers with thousands upon thousands of bright red little craving reminders might not be the best way to dampen public smoking.

Smokers crave nicotine. All they need is a reminder, any reminder, and the urge to smoke is triggered—whether it’s a picture of a lit cigarette, a picture of a lit cigarette with a red line through it, a really scary warning label, or anything else smoking-related.

Now, to be fair—and to get back to our main topic—if a smoker has gotten far enough to see one of these new warning labels, it means they already have a pack in hand, and their craving is full-blown to start with. It’s not like the government is handing these images out to unsuspecting passers-by (at least not yet). But the “no-smoking signs” finding is a related example for my bigger point, which is that heavy-handed public health measures can backfire if you don’t understand the details of human psychology. As concerns the present case, the best way to win someone over, it turns out, is not to broadcast that they’re an idiot for doing what they’re doing. Even if they are an idiot for doing what they’re doing.

In closing, let me state that I’m no fan of smoking. I think it’s gross. And clearly it’s bad for your health. Furthermore, I think efforts to reduce public smoking are probably a good thing—especially considering the harm that can be done to innocent third parties, through second-hand smoke and through the boosted healthcare costs everyone has to shoulder when smokers end up in the emergency room [Note: readers have disputed this “healthcare” claim; see comments section].

But you have to be smart about how you try to change behavior. People are pretty sensitive to the means you use, and paternalistic condescension, or shrill reminders about truths you already know, are unlikely to be very effective. They might even blow right back in your face.

[Update: I’ve changed the title of this post from something unfunny and glib to something cleverer and more serious, in response to a thoughtful reader comment and my own reflective judgement. Sorry if you miss the old one.]

I shall now qualify my own post. See this article: http://www.voanews.com/english/news/usa/Health-Experts-Welcome-Graphic-New-Warnings-on-US-Cigarette-Packages-124384294.html. It says, "Studies have shown that similar campaigns have significantly lowered tobacco use in Uruguay, Brazil, Canada and Australia." If those are good studies, then — so be it (though I'd like to see them). In other words, if the outcome is overall less smoking, then, in at least one sense: mission accomplished. But I still have a concern about means — about how you get there. And something certainly grates about these images. From the same article, Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius is quoted as saying, "With these warnings – every person who picks up a pack of cigarettes is going to know exactly what risk they're taking." Maybe that's what's so annoying. It's not that people don't know the risk they're taking … maybe that was the case in the 50s and 60s. But now, everyone knows. So if this campaign turns out to be effective–irritating though its tone may be–it's not going to be due to the stunning new realization that smoking is bad for you.

Now that I think about it (as I continue this dialogue with myself), I'd REALLY like to see those studies showing that similar campaigns have causally lowered smoking in those other countries. How was that established? How did they isolate the campaign as the variable responsible, against all the other possible causes? What does "significantly" mean — to a statistically significant degree? Was there a control population matched on every dimension? How could this even be shown?

The thoughts on reactance are interesting, but do they really bear out the shrill insistence of the title that this is "the stupidest idea ever?". Psychologists have been directly studying the effects of graphic warning labels on the psychology of smoking – and it appears that they have at least a small impact on both awareness of the risks of smoking, thoughts of quitting, and actual rates of quitting (and they do so across cultures):

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14660774

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21084424

Why have a round-a-bout discussion regarding the efficacy of these warning labels when there is a wealth of data to discuss already?

Also: A small point about "wear-out" – it doesn't imply an 'arms race' towards ever more graphic imagery. The point about wear out is that the axis of the imagery should change. You see this in transport accident campaigns which shift focus every few years – a good example is the Victorian TAC's shift from graphic imagery of car crashes, to ads which emphasised the emotional distress which traffic accidents cause, to ads which emphasise the legal implications. A similar shift has started in Australian tobacco warnings, which have been quite graphic for many years, and are now shifting towards emphasising the health benefits you can accrue from stopping smoking.

Dear Jon,

Thank you for your thoughtful–and informative–reply! I had hoped my title would come across as self-consciously glib and funny (rather than shrill–clearly these labels aren’t actually the STUPIDEST idea EVER) but I can certainly see how it would be easy to take it in the way you did. The research you’ve linked to is very interesting. I have two ways of responding to it. The first is to say that I wanted to introduce and communicate a few ideas from psychology, especially reactance, and the current news item provided a good platform for this, at least conceptually. (I also wanted to discuss "backfiring" effects in general, as a selfish way to justify discussing my own research on no-smoking signs.)

The second way to respond is to address the research itself. I’ve given it a quick read, and the following idea occurs to me. It seems more than plausible that something like experimenter demand plus self-consistency pressures explain these data. Here’s what I mean. Suppose I’m a smoker and a scientist calls me up and asks me if I’ve seen these gruesome new warning labels on cigarette packs. Let’s say I have. The scientist asks me if I’ve thought a lot about warnings, discussed them with others, etc. — the measure of "cognitive engagement" used in the study. Let’s say that I have. "Yep," I say, "I’ve seen those warning labels, saying that all sorts of terrible things will happen to me if I continue to smoke, and I’ve definitely spent some time thinking about that." Ok, now the scientist asks to what extent I plan to quit smoking, i.e., the measurement of "intention" in the study. At this point, if I’ve already said all that, I’m going to look pretty silly if I tell you that I plan to keep on truckin’ on with my habit. So I might say that I intend to quit for at least two reasons: a) to not appear silly to the scientist or b) to not feel inconsistent with my own prior statements, i.e., the well-known self-consistency bias that crops up in self-report surveys like this. Now we can extend our reasoning to the follow-up survey asking about actual cessation behavior. It’s a self-report recall measure, which means that I have to a) accurately remember my actual smoking behavior from over the past few months and b) report that information honestly to the scientist (to whom I’ve already said I was going to quit). That both of those hold might be a stretch. But let’s say that they do: let’s say that I actually do smoke less after the phone call from the experimenter. Well, this could be due to the fact that I told someone I intended to do so, and self-consistency pressures exerted themselves on my actual behavior over time. In this case, it would be the event of the experiment itself leading to the smoking decrement, rather than the warning labels themselves.

There’s another possible explanation. What if the correlation between cognitive engagement, intention, and cessation is a real correlation? Even so, we cannot conclude that the warning labels caused the intention/cessation. It’s the old problem of direction-of-causal arrow. What if smokers who ALREADY have the intention to quit smoking (because they’re really concerned about the health risks, for a number of independent reasons) are the very same smokers who are likelier to notice the warnings, think about them, talk about them with others, and so on. This seems like a highly plausible explanation for the correlation — or at least a partial explanation.

Hence the studies you shared are inconclusive at best. They suffer from the same sort of problems that self-report, correlative studies generally suffer from, with the added special likelihood of experimenter demand effects (telling the experimenter what they want to hear), self-presentation effects (telling the experimenter what makes you look good/reasonable/not like an idiot), and self-consistency effects (telling yourself what would make you be consistent–and inferring your own intentions and emotions therefrom).

Of course it’s POSSIBLE that the studies show just what they claim to show. But given the robustness of the considerations I highlight in my blogpost, I think it’s best to approach the data with some skepticism and caution.

On the point of wear-out … The government’s desire to avoid this phenomenon (assuming they have it) certainly doesn’t ENTAIL an arms race, but it doesn’t rule one out, either. Their strategy so far has been to "ramp up" the shock value. They may get wise and do what you propose: i.e., switch the axis of the imagery moving forward, and that would certainly be a good thing. My point was more that IF they ramp up the gore, THEN it’s likely that reactance will go up, too.

Really good reply, and thanks for pushing back on some of my points.

Best,

Brian

Brian, I have deconstructed the Canadian study they cite. Or rather, I should say, I found what they decided to ignore. Here it is, excerpted from my own testimony at a health dept. hearing:

The studies you cite to assert its effectiveness to support this proposal do not measure any actual smoking cessation. They only measure how informed smokers are about tobacco risks. (4, 5, 6) You lean on Canada for your evidence since they have had a wide array (depicting many alleged health effects) of graphic pictures on their cigarette packs since January 2001 and cite from one of their studies that "46% [of youth] report that the pictorial warnings have been effective in getting them to try [not actually doing it] to quit smoking." (6) But the small print for that figure — indeed all their results — says "These numbers should be interpreted with caution, due to small sample sizes." Additionally, you cherry-picked the last year's figure available (2004) when the study covered a number of periods from December 2000 to Nov-Dec 2004 when the same question was asked. Since the important measure here is effect from these warnings it's unfortunate you ignore that immediately prior to the institution of the graphics (Jan. 2001) 56% said they would try to quit smoking! It declined to 41% immediately following the release and peaked at 63% in Nov-Dec. 2001. The last reported figures show that if there's any validity to these results it's that effectiveness wanes. In fact, to quote from page 41: "[T]he current results also suggest a decrease in the number who say these messages have been very effective in increasing their desire to quit." To quote from page 35: "The current results also indicate an increase in the number of youth who say they can remember none of these messages."

(4) O’Hegarty M et al. (2006). Reactions of young smokers to warning labels on cigarette packages. Am J Prev Med 30(6):467-73.

(5) Hammond D et al. (2006). Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels in informing smokers about the risks of smoking: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Ctrl 15(Suppl 3): iii19 –iii25.

http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=16754942

(6) Health Canada. The health effects of tobacco and health warning messages on cigarette packages – Survey of youth: Wave 9 surveys. Prepared by Environics Research Group, Jan 2005

http://www.smokefree.ca/warnings/WarningsResearch/POR-04-19%20Final%20Report%20-%205552%20Youth%20wave%209-final.pdf.

Dear Audrey,

Your post here is incredibly valuable. May I ask you more about your work? Maybe you can send me an email and we can be in touch about these ideas.

I wonder to what extent social agendas are driving non-rigorous research efforts to justify heavy-handed techniques at persuasion — techniques which a lot of robust psychological theory should predict won't work. You might be interested to know that the "no smoking" study my colleagues and I conducted was initiated through a line of work on unconscious semantic processing focused on negation, and the "no smoking" example came up only incidentally as a possible test case. Once I presented our results, I saw that the finding was drawn into a sort of anti-nanny-state narrative, especially by, e.g., the Daily Mail and its readers, as well as other libertarian-leaning blog sites, and so on. But I'd like to see these types of studies conducted in the most rigorous way possible without respect to policy-justification or non-justification (or at least not motivated by those considerations). A few advantages of our no-smoking study over the correlative self-report surveys cited by Jon in the reply section to this post are: that it employed an experimental design, that participants did not know what we were testing, and they showed the effect even when they were unconscious of the prime. That sort of experiment seems impervious to self-consistency biases and experimenter demand issues, and it's the sort of research that I hope will catch on in this area with respect to informing public policy.

Brian

Brian, I appreciate your appreciation 🙂

It's my opinion that social agendas are "driving non-rigorous research efforts to justify heavy-handed techniques at persuasion" to the fullest extent. Most, if not all, of these studies begin with a preconceived conclusion. All they need is someone to fill in the blanks. That is why your study would be drawn into the narrative you describe. When an apparent non-agenda driven (impartial) researcher arrives at conclusions contrary to those that are, on a subject that is rife with methodologically questionable studies so transparently designed to advance an ideology, it's absolutely going to be latched onto by those who have been trying to expose the falsehoods and into the raging debate that exists.

Another aspect you need consider is the power the policy-justifying cabal holds over research in this field. You "accidentally" fell into it. But those who would seek to conduct truly rigorous study but whose unfolding conclusions would not meet with the dogma are threatened (loss of funding or job), blacklisted, and publicly condemned. Please see Dr. James Enstroms site for an eye-opener on this: http://www.scientificintegrityinstitute.com/defense.html

You can email me at nycclash@nycclash.com

Audrey,

Thanks for your reply — and the link you included as well. Looks like a pretty interesting institute, doing evidently very important work. The really funny thing about this whole debate is that, in terms of outcomes, I'm more or less on board with those who would like to see less smoking in society …

Whenever a mass of individuals engage in an activity that's seriously and predictably damaging to their health, they, collectively, put a preventable strain on the healthcare system. This system is one for which we're all responsible through taxes (including people who don't engage in the activity). Hence I think those individuals cause harm to others by their actions (whether the actions are completely voluntary, or less so, due to addiction), and their behavior is morally problematic just to the extent that it causes that third-party harm.

If smoking were damaging to one's own health only — with no ill-effect on anyone else — then I would feel very differently. People have a right to self-harm. Or, more than that, to decide what constitutes (self) harm … many smokers would say that, on balance, a life lived with cigarettes increases their subjective well-being, even if it may shorten their years on Earth. In some cases this may be self-delusion, radical discounting of future pain, or behavior-justification; but I expect in many cases it's true — that is, subjectively true for the smoker making the argument.

So while I'm strongly in favor of individuals' rights to make their own choices–and opposed to unnecessary infringements of personal liberty–I think that this particular "tragedy of the commons" problem does lend legitimacy to organized efforts to reduce smoking.

The question is, though, how do you do it? I think the means are important, for two reasons. One, some means may be, in themselves, problematic — even if they lead to the "right" outcomes — because they violate certain other values, such as respect for autonomy, non-condescending relationships between entities, or whatever. Two, sometimes they are important precisely because of a concern about the outcome, such as in cases in which the wrong means lead to the wrong outcome.

I think some of these heavy-handed anti-smoking measures are (arguably) wrong on both counts. Not only do they set up a paternalistic and condescending dynamic between the government ("which knows what's best for you") and smokers; but these measures may not actually reduce smoking and, worse than that, may increase it!

And this is where the science comes in. Independent of any of the moral or political considerations I've just been talking about, there is an objective fact of the matter about whether second-hand smoke leads to deaths, whether smoking signs trigger cravings, and whether grisly warning labels causally reduce smoking, drive people to quit, etc. In some cases the web of causes may be so complex that, with the current state of science, we cannot actually make contact with this objective fact. But I don't think we're that far in the dark. I just think we do a lot of bad science. We also mistake correlations for causations. We ignore alternative explanations, etc.

Anyway, by now I'm re-hashing our prior exchange. I'll leave it here for now. I'll be interested in your response.

Brian

It has been argued that smokers cost less than non-smokers in the long run, given that they tend to die earlier, and contribute a large amount in taxation:

http://www.adamsmith.org/blog/health/fatties-and-smokers-save-the-nhs-money/

Sorry I couldn't get back to you sooner but…. better late than never? 🙂

Anyway, what I THINK shines through is that you wouldn't let your personal opinion cloud your work. If the research is done right and it proves contrary to your preference it appears that you would have the integrity and ethics to admit it and accept it. On this subject, and if I'm correct, then you are the rare case. To use an over-used phrase… a welcome breath of fresh air.

Now, considering all else that remains debatable (e.g. secondhand smoke, signage, etc.) and really rather weak, if YOUR case for supporting less smoking rests on the alleged financial cost to society alone then, as Matt Sharp noted, you might have to rethink it. Because aside from a handful of studies that find otherwise we're also back to needing to consider WHO conducts the studies that arrive at that conclusion. Just off the top of my head I remember one that was reportedly conducted by an actuary (and it was an actuarial report). But a close look and you find that it was co-authored by an anti-tobacco researcher with no background in this field. It screams pretty loudly that he was calling the shots and the actuary was filling in the blanks.

Nevertheless, I'll give you those handful of studies/reports that find that the opposite is true; that smokers more than pay their fair share and actually subsidize non-smokers (I copy and paste from my own site):

<b>Fat People [And Smokers] Cheaper to Treat, Study Says</b> – (February 5, 2008) –

(http://medicine.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.0050029)

In a paper published online in the Public Library of Science Medicine journal, Dutch researchers found that the health costs of thin and healthy people in adulthood are more expensive than those of either fat people or smokers… Cancer incidence, except for lung cancer, was the same in all three ["healthy living," obese, smoker] groups.

Ultimately, the thin and healthy group cost the most, about $417,000, from age 20 on. The cost of care for obese people was $371,000, and for smokers, about $326,000.

Note: And yet when Philip Morris released a report conducted in the Czech Republic in 2001 that found the same the anti-smokers played the emotional trump card and attacked them for drawing the public finance conclusion that smokers statistically die younger. Philip Morris was wrongfully forced to apologize for an economic report that did no more than substantiate what the anti-smokers claim themselves: "Smoking causes 'premature' death" [and thus savings]. Read more: http://www.pierrelemieux.org/artmorris.html

Related

<b>Does Staying Healthy Reduce Your Lifetime Health Care Costs?</b> (Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, May 2010): Our main finding is that although the current health care costs of healthy retirees are lower than those of the unhealthy, the healthy actually face higher total health care costs over their remaining lifetime. At any given age, average costs for people who remain in good health are higher than for those suffering from one or more chronic diseases. So why do the currently healthy incur higher lifetime health care costs than the sick? First, people in good health can expect to live significantly longer. At age 80, people in healthy households have a remaining life expectancy that is 29 percent longer than people in unhealthy households, and, therefore, are at risk of incurring health care costs over more years. Second, many of those currently free of any chronic disease will succumb to one or more such diseases. For example, our simulated individuals who are free of any chronic diseases at age 80 can expect to spend one-third of their remaining life suffering from one or more such diseases. Third, people in healthy households face an even higher lifetime risk of requiring nursing home care than those who are not healthy, reflecting their greater risk of surviving to advanced old age, when the risk of requiring such care is highest.

http://crr.bc.edu/images/stories/Briefs/ib_10-8.pdf

<b>The Proposed Tobacco Settlement: Who Pays for the Health Costs of Smoking?</b> (Congressional Research Service, April 30, 1998): Smoking has apparently brought financial gain to both the federal and state governments, especially when tobacco taxes are taken into account. In general, smokers do not appear to currently impose net financial costs on the rest of society. The [MSA] tobacco settlement will increase the transfer of resources from the smoking to the nonsmoking public.

http://www.forces.org/evidence/files/crs_97-1053.htm

<b>The Health Care Costs of Smoking</b> (NEJM, October 9, 1997): If people stopped smoking, there would be a savings in health care costs, but only in the short term. Eventually, smoking cessation would lead to increased health care costs [7 percent higher among men and 4 percent higher among women].

http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/337/15/1052

Insurance Costs of Smoking (from Secondhand Smoke: Facts and Fantasy by W. Kip Viscusi, 1995): On balance, smokers save society 27¢ per pack from an insurance standpoint. This amount excludes the role of the taxes smokers pay, which average 53¢ per pack [in 1995] of cigarettes.

(Sorry, the link I have is suddenly dead after all these years and I don't have time right now to run down another)

A note to commenters: if your comment has links in it, we hold it for manual moderation. This is because spam comments always have links in them.

Hi Audrey,

I'll reply to your later post here, since there's no 'reply' button under your later comment.

I haven't looked through all of the original studies you cite, but it seems very plausible that smokers' dying early (coupled with their huge tax contribution) could actually reduce, rather than increase, cost pressures on the healthcare system, just as you suggest. If that's the case, then my "third-party-harm-through-monetary-cost" argument is defeated (unless there are some other monetary costs I'm not thinking of).

That would leave the actual-health-harm-through-second-hand-smoke argument, as well as, I suppose, emotional-harm-caused-to-friends-and-family-through-smokers'-suffering-and-early-death argument, which I haven't yet made.

In short, that argument is that smokers who choose (in full knowledge of the addictive and health-damaging properties of cigarette-smoking) to smoke, become addicted, and suffer and die early, cause preventable harm to their loved ones by forcing them to endure the lung cancer, the hospital visits, etc. I haven't actually heard anyone make this argument, but it occurred to me just now. What do you think of it?

I think maybe the thing to play up to kids who are deciding whether to smoke or not, is the psychology of addiction. That is, rather than saying, "smoking is addictive" … spell out what it MEANS to have an addiction. Spell out what your psychology does to justify an addictive behavior, discounting future pains, and so on, so that people really CAN make their decisions about whether to self-harm in a meaningfully "informed" fashion. I wonder if people who choose to smoke just don't get what happens to their psychologies. Because while it might feel like a good idea now, NOBODY likes having lung cancer when they get it. This human inability to treat the future as seriously as the present is a flaw in our intuition system. And I think people need to know about this flaw, or libertarian informed-free-choice arguments start to break down.

All that said, as far as the actual means of influencing behavior, I hold to my objections on the heavy-handed methods on two grounds: the outcome-grounds (i.e., I don't think the weight of well-gathered evidence suggests that these warnings will actually work), and the means-grounds (i.e., I think there may be something intrinsically morally problematic about condescending government-citizen relationships, etc.)

Really grateful for your thoughtful replies to this post, Audrey.

Brian

Hi again Audrey,

Someone else has made the harm-to-loved-ones argument. See here: http://www.quitsmoking.com/info/articles/affectseveryone.htm.

I'll add one more point I forgot to mention. The study materials are not explicit about the order of presentation of questions. The self-consistency bias is much likelier to occur if they FIRST report on cognitive engagement and THEN report on intention to quit. I'd love to see the original survey to see which order they used.

Matt — there's no reply button on your post, so I'll reply here. Thanks for your comment. I had been thinking, in the back of my head, about this possibility … perhaps I've come across that argument before. I haven't seen the studies, so I can't evaluate them. But assuming that's right — i.e., that smokers (and the obese) actually burden the healthcare system LESS, then that would remove a major plank of my argument.

Then we'd be back on the territory of simple autonomy and choice. That is, if it's true that third parties aren't harmed (though we have to take into account second-hand smoke; but let's set that aside), then my libertarian biases take over and I say: if people want to harm themselves, of their own free choice, then that's their right.

But then, what shall we say about free choice? The relationship between freedom and addiction is pretty messy. We don't consider children or the mentally ill totally free to make their choices, due to reduced mental capacity. Are the addicted meaningfully free in the sense required for libertarian arguments? I'm not totally sure. One worry I have about my own libertarian leanings is that they seem to be tied up in a view of humans as rational creatures. Give them the info, and let them do what they will. Let them choose. But what psychology has been telling us for a long time now is that human choice is much more fragile and susceptible to influence than we are intuitively inclined to think. If my nicotine-loving sub-system is biasing my judgement beneath the threshold of consciousness, for example by drastically discounting future suffering in way I'm going to hate myself for later — then am I making an adequately free choice when I say, "bring on the cigarettes" ?

Brian

Geez, that's ubnelievable. Kudos and such.

Very interesting and thought-provoking post, Brian. Do you have any advice with regard to literature on the self-consistency bias?

Hi Lisa,

Thanks for your interest. I don't have a particular "favorite" article on this topic, but try this for a start:

The quest for self-insight: Theory and research on accuracy and bias in self-perception. Handbook of personality psychology.

Robins, Richard W.; John, Oliver P.

Hogan, Robert (Ed); Johnson, John A. (Ed); Briggs, Stephen R. (Ed), (1997). Handbook of personality psychology, (pp. 649-679). San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press, xxiv, 987 pp. doi: 10.1016/B978-012134645-4/50026-3

Best wishes,

Brian

I take the points about the effectiveness of these campaigns in actually getting people to quit as they are presented here at face value – that is, that they are not effective at all.

However, what of the possibility that these kinds of images serve to better inform the public about the effects of smoking? That is, can we say that graphic labeling of this sort actually helps us to (simply) inform the general public about the effects of smoking, divorced from the objective to actually influence their behavior? Certainly, as things stand at preset the agenda is clearly to get people off cigarettes, but it could also be argued that there is a closely related but ultimately distinct goal of Public Health authorities, as part of liberal democratic society, to provide the most relevant and comprehensive information to the public. Can we say that, whether or not people continue to smoke or even smoke more than before, that as a result of these campaigns people are more aware, in a meaningful way, of the effects of smoking?

My speculative answer to that is Yes – the public is more and better informed about risk of smoking tobacco. The visceral and emotive component supplied by these images at the very least helps contextualize and better comprehend otherwise potentially dull and nonaffective facts about smoking. If this is the case than the use of these images seems to me justified, for even if it leads to increase in smoking, this will be the result (ex hypothesi) of informed choice in behalf of individuals and as such beyond the purview of governments of liberal democratic societies.

Dmitri —

This is a very interesting idea, and thank you for putting it forward. I think I'd be more sympathetic to your view if the information on these particular warning labels were actually … informative. But due to the nature of the message, there's not a lot of info there: "Smoking kills." Or "smoking causes cancer." Well, ok … but who doesn't already know that? Now, if you could show me that a lot of people — especially those who are at a risk for taking up smoking in the first place, say, young people — actually DON'T KNOW about the consequences of smoking (in a way that makes that knowledge relevant to and sufficient for 'informed choice' type arguments) — then I think you'd have the first block of a foundation laid for your argument.

But even if we granted that much — i.e., that there really is a lack-of-knowledge problem — I'd still wonder if dissemination of that knowledge, by a Public Health agency charged with protecting the public health — could be morally justified if it were KNOWN to increase dangerous behaviors (through ironic psychological processes, based on the fact that humans are not rational-choice machines as classic economics supposes) and actually jeopardize public health. There would be something pretty fishy about that, and it would make me regard your argument with increased skepticism.

That's my first stab at a reply. I'll think about this some more. In the meantime, what do you think of my response here? Did I give your proposal a decent reading? I want to make sure I respond fairly to your idea. It is very interesting indeed.

Sincerely,

Brian

I do see your point that the emotional presentation of the knowledge on these particular labels may 'increase' their informativeness in a different way, i.e., along a nonrational or non-cognitive dimension. And that increased knowledge may be important for a theory like the one you propose. But let's say we grant that. Does it overcome the objections I brought up in my last comment? What do you think?

Matt — I replied to your comment somewhere up there in the chain. Just so you don't miss it …

Brian, your points about the potential drawbacks of graphic cigarette warnings do seem important and compelling. However, I wonder if, on consideration, the available evidence really weighs against implementing the warnings.

You offer a number of reasons based on background psychology (reactance, wear-out and cueing) that the policy could be ineffective or even potentially backfire. Fair enough. But surely we should also look at the background psychology that would indicate such warnings might be effective. The most obvious would be simply enhancing perception of risk and tapping into risk-avoidance. While I agree that almost everyone realizes that smoking is harmful and is linked to, e.g., lung cancer, and this holds across income and education levels (one 2005 study puts that knowledge at about 95% among adult smokers in the US: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/15/suppl_3/iii65.abstract), the degree of perceived risk varies somewhat. For instance, a 2005 Gallup poll found that 81% perceived smoking as very harmful, 16% as somewhat harmful, and 3% as not at all harmful. The effect of such warnings could plausibly shift risk-perception at the point of purchase from the ‘somewhat harmful’ to the ‘very harmful’ camp, making individuals less likely to buy cigarettes.

A related element of background psychology that might lead to the warnings’ efficacy will be triggering the fear response, which seems sensitive to more extreme presentation. (e.g., http://heb.sagepub.com/content/27/5/591.abstract?ijkey=3e3ab1e78c001de5565af3bf8fecb69d879f0bc6&keytype2=tf_ipsecsha) This could trigger reactance, certainly – but it could also trigger avoidance. The meta-analysis makes a good point on this score: “Because these two responses cancel each other out (i.e., if one is defensively responding to a fear appeal and rejecting it, one is not making attitude, intention, or behavior changes), it is difficult to tell whether danger control or fear control processes are dominating unless one has measured and/or manipulated perceived efficacy.” (p. 601) The upshot is, I think, that we cannot conclude with certainty based purely on background psychology whether the policy will be effective.

So is the more direct evidence point to the effectiveness of graphic warnings? You point to some relevant flaws in the survey-based data, and I would agree that the supporters of graphic warnings would be on much firmer ground if there were actual controlled experiments testing smoker behavior in the face of graphic warnings. Still, it is noteworthy that most of the evidence I’ve come across points towards the effectiveness of these policies – or, in the very least, suggests that they will not backfire. I would also like to point out a very interesting 2009 study looking at national-level effect of warning implementation: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/18/5/358.full.pdf . This interestingly shows a bump in the extent to which labels seemed to make Australian smokers think about and be motivated to quit after Australia introduced graphic labels; a similar but smaller bump occurred in the UK after it introduced text-only warnings. Also, after the new policy in Australia, more Australians sought assistance in quitting via at least one popular call-in service. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2679186/ ) To be sure, such national-level studies are not decisive. It is difficult to disentangle the causal effect of the warnings from other changes; concurrent policy changes, such as increased TV advertising and the general political discussion of the issue, could have contributed to these changes – or perhaps some tertiary, coincidental factor. But taken in conjunction with the previous survey data, I think this provides strong evidence that such behavioral and attitude shifts are at least in part due to the new warning labels. In the very least, they indicate that such policies (perhaps given that they are accompanied by a general anti-smoking campaign), at least in the near-term, are not likely to backfire and increase cigarette usage.

That having been said, the same national-level data points towards a robust wear-out effect. Any initial boost seems destined to taper off as people get used to the labels. Nevertheless, it is not clear that such will taper off to the same levels they were before the labels were put in place. Moreover, I think even a temporary boost in avoidance of cigarettes/desire to quit would be a significant policy achievement in an area as difficult as smoking policy.

Dear Mr. Shaefer,

Let's say that the warnings shift risk perception at the point of purchase, as you suggest. What evidence do we have that this shifted perception will actually lead to less cigarette-purchases? That further link needs to be shown. Probably a majority of smokers are in the camp that knows cigarettes are "very harmful" — yet they buy the darn things anyway. Why? A big reason, I guess, is that they're addicted, and addiction plays all sorts of funny tricks on the pathway between knowledge (including knowledge of risk) and behavior.

You write: "The upshot is, I think, that we cannot conclude with certainty based purely on background psychology whether the policy will be effective." I certainly agree with you here! What is needed are controlled, experimental studies, which isolate the warning stickers as causal contributors to decrements in smoking. The correlational studies we've been discussing in this comments section just aren't convincing (for the reasons I've given). This isn't a trivial point: they're NOT good studies, and even if the correlation is genuine, I can't see that we have good reason to suppose the causal arrow runs from stickers to cessation. Based on your response, it seems like we're on the same page about this.

Finally, I want to reiterate a point I've been making throughout this discussion. Even if we had CONCLUSIVE evidence that these warning stickers were overall effective in reducing public smoking, I'm not sure that would make me in favor of them. This is because I think there is more to consider in public health policy than brute outcomes. Means matter too. And if the means used set up a condescending relationship between the government and smoking citizens, they may introduce certain other harms or moral messiness worth considering on their own.

As an analogy (but only a very blunt and overreaching one), putting everyone in jail would reduce violent crime. If less crime is what you want, this would work (given resources; obviously this is a fanciful scenario). But in this case, the relationship between the government and the citizenry would be corrupted on moral grounds alone — independent of outcome.

What do you think?

Brian

Brian,

I suppose I half-agree with you: we do need such controlled experiments. But I disagree about the value of current survey/correlational studies. I think they do give us valuable information, and do provide at least some evidence (even if it's not conclusive evidence) in favor of the hypothesis that the labels will lead to reduced use. Correlation doesn't imply causation, to be sure, but it seems to me that the best explanation of those studies’ various converging results is causation. And, moreover, I don't think we should always wait for conclusive controlled experiments before putting forward psychology-based public health measures. What we have now is background psychological theory that's basically neutral about the effects, and survey/correlation-based evidence in favor of the policy. I haven't seen much survey/correlation-based evidence (measuring the effects of these sorts of warnings in particular) to suggest that they will have a neutral or backfire effect, though I admit I haven't done a thorough survey and perhaps such evidence exists. This, I think, tilts the scale enough to lend credence to the belief that the warnings will reduce usage.

As for the moral question – this is a thorny issue, but I don't think universal jailing is analogous here (unless you meant it to simply illustrate the point that some means to a good outcome are unethical, which of course I agree with). Draconian or authoritarian 'solutions' to crime are morally abhorrent based primarily on their coercive nature, rather than the 'condescending' relationship they set up. Warning labels are not coercive – or at least, not to the consumer. I suppose, then, I’d like to know in more detail what this moral objection amounts to. One thought: does the moral objection apply to graphic warning labels but not, say, TV advertisements or the current textual warning labels on packs? If yes, I would reply that it’s hard to see how the former is any more condescending than the latter, and arguments in favor of the permissibility of ads and textual warnings should apply to graphic warnings. If the objection applies to all of these – well, then we seem to have a broader objection to government-sponsored attempts to limit smoking use (and the objection surely applies to coercive means as well, e.g., cigarette taxation). There is not nearly enough space here to respond to such libertarian-leaning objections, except to say, if they are apt, then we don’t actually need the controlled experiments discussed above – the empirical question is irrelevant if the labels are impermissible even if effective. But on the contrary, I’m inclined to think, as you suggested in another reply above, that such non-coercive interference is at least permissible (when effective) in cases like addiction, where irrationality seems to be pervasive.

-Owen

Owen,

I didn't see your comment, here — sorry for taking so long to reply. I think this is a fair and well-reasoned response. I'm not sure I can join you on the value of the correlational studies that we have. Not only do they fail to show causation — a point on which we readily agree — but the correlation itself seems too handily explained by flaws in experimental design. In other words, I'm not sure that they constitute any good evidence, at all, for even a meaningful correlation, much less for causation. We could quibble about this back and forth, but I guess we just fall on opposite sides of the fence when it comes down to it. I don't think your position is unreasonable.

Yes, my moral argument is tricky — it's an initial offering, a sketch. I haven't thought it through. The way I've outlined the idea, it sounds like I'm saying that there's something intrinsically morally problematic about state-citizen condescension, and that such condescension is SO morally problematic, that it should be avoided EVEN in the face of clear causal evidence that the "outcome" works: i.e., that smoking decreases. I admit that this would be difficult to make convincing, but I wanted to float the idea because it does accord — at least somewhat — with my intuitions in the matter. If others find the idea plausible, then maybe we could tease it out; if it seems outlandish or impossible to support, then I might give it up. But I want to play around with it for a while.

Thanks for your very useful contributions to this discussion, Owen.

Sincerely,

Brian

Mr. Schaefer,

Thank you for your well-reasoned post. I want to take some time to look through the research you've included; I'll reply fully as soon as that's possible.

For now,

Brian

A reader emailed me separately to draw my attention to this 2008 NY Times article making the same "backfiring" prediction I have made, with some FMRI data to back it up:

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/12/opinion/12lindstrom.html

Dear Brian,

thanks for you post. I enjoyed reading it and really think it's getting straight to the point. Useless to say that I agree on many respects with your conclusions. Just let me add a short comment on one of your final points about issues of costs imposed by smokers on the health-care system. Are you actually sure a smoker is such of a burden to the community all things considered? I am tempted to think that this kind of thought is not actually proven. Taxes for cigarettes are quite high I would say, so smokers are already payng their bit for the supposed cost of their treatment should they get smoking-related illnesses. Moreover, if it is true, as it is, that smokers tend to live less, then one could argue that they will be living less years in retirement. This, again, would amount to a reduced cost for the community. I'm saying this from a smoker perspective, since I am worried that smoking could be more and more associated with social stigma, which I think it is something should be avoided. Having said this let me restate the overall appreciation of your post.

Cheers,

Paolo

Dear Paolo,

Thank you for your reply. You make a good point, and a few other readers have brought this up as well. For example, Matt Sharp wrote:

"It has been argued that smokers cost less than non-smokers in the long run, given that they tend to die earlier, and contribute a large amount in taxation: http://www.adamsmith.org/blog/health/fatties-and-smokers-save-the-nhs-money/"

As I've written in some of my above replies, this general sort of argument makes sense, and I wouldn't be surprised of the data supporting it turned out to be robust. So I'll look into it some more, but I'm prepared to give up the "burden on the healthcare system" argument in light of evidence.

Also, it's interesting you bring up the point of social stigma. Another reader emailed me separately to discuss that idea. I am curious about negative side-effects associated with stigma, and (if I have some time) will try to find some research on that topic.

Best,

Brian

Hello Brian,

Actually, I just sent you another email with a link about stigma and its attendant isolation, but, to deal with some of the subjects on board:

I believe your assumptions about smoking and "addiction" are off-base. Especially since you seem to assume that the habit of smoking is somehow as mind-bending and mentally impairing (at least in terms of judgment and free will) as, say, a hopeless addiction to heroin. Not true, or not true for, I'd guess, 90% of smokers. Just as it's not true for the vast majority of people who drink alcohol and don't become (hopeless, impaired) alcoholics. Then, too, consider that caffeine is addictive. In fact, one researcher called it "the most widely used addictive drug in the world." and yet nobody (yet) sneers at caffeine addicts, or assumes they're round the bend and incapable of deciding clearly whether or not to have that afternoon coffee break. Or scoffs at their testimony that having a cup of coffee at their desks while they work, sharpens their focus and enhances their performance. So why doubt smokers when they say the same thing?

Study: smokers perform better than nonsmokers at both mental and physical tasks:

http://dengulenegl.dk/English/Nicotine.html

The argument that "smokers cost more" has been dealt with, but I'll remind you that if we start agreeing to agitate (self-righteously, coercively) over Things That May Represent A Cost to Society, then I'd say single motherhood is probably #1.

And as for costs to employers, diabetics are by far the most "expensive" employees– said, by the NY Times, to cost employers over 13K a year. ("Diabetics in the Workplace…" Dec 26, 2006)

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/17/opinion/l17smoking.html?partner=rssnyt&emc=rss

Hi Linda,

A very reasonable reply — and thank you for pushing back on some of my speculations about addiction and free will. I'm sure that very many smokers are not so addicted to nicotine that they fall into the same class as someone hooked on heroin. My argument, then, would apply only to those people who are or who become (hopeless, impaired, as you put it) nicotine-addicts. And I expect this is a very large number of people (though not equal to the total number of smokers, as you fairly suggest.)

To tease apart a subtlety. Most of the research I've seen on caffeine is that it has mostly good effects on health, memory, and so on. You don't see coffee addicts in emergency rooms. Cigarettes seem to have a much higher harm-impact, and while a quick smoke might sharpen someone's focus at work (who says it doesn't? who scoffs at this?), a lifetime of quick smokes harbors many times the risk of serious suffering and premature death than a lifetime of coffee breaks … so I think the cases are meaningfully different.

For now,

Brian

I think you've reached an a priori conclusion on the number of smokers who are (deeply, chemically) "addicted;" either that, or you've based it on received, but flawed, wisdom. Go out in the world and ask actual (and not yet brainwashed) smokers (who, until recently, were simply said to be indulging in a habit). And don't confuse "hard to quit" with "addicted." It's hard to quit a bad love affair. Or the daily "fix" of social media. Or to stay on a strict diet, abstaining from the foods that you "habitually" like and that consistently offer pleasure and comfort. We are, as a race, "creatures of habit."

In fact, the rising eminences of Public Health have already begun tarring fat, sugar and salt as "addictive substances," (see especially the screeds ex FDA chief David Kessler) which, first, leave consumers in their helpless thrall, and then lead them to endless parade of diseases and Emergency Room visits and lost productivity and massive expense. And food is about to become the next Public Enemy.

(Chocolate, by the way, hits the same receptors in the pleasure spots of the brain as a cigarette does. And so does sex. ) Is pleasure "addictive"? Using addictive in the broadest but incorrect sense of the word, it probably is.

Then, too, if nicotine itself were addictive, the patches and gums and substitutes should "work" the way methadone works. But careful meta-analyses indicate they fail over 98%. Here, for instance, is just one example:

Dr. Michael Siegel professor at Boston University's School of Public Health and longtime anti-tobacco activist:

<i>"With a long-term smoking cessation percentage of only 1.6%, one can hardly call NRT treatment an 'effective' intervention. Even though the 1.6% abstinence rate is better than the 0.4% achieved with placebo, no one in their right mind would consider a 1.6% success rate with NRT to be 'effective.' In fact, the logical conclusion from this paper is that NRT was a dismal intervention. The overwhelming majority of smokers – 98.4% – failed to achieve long-term sustained abstinence with NRT treatment." (16)</i>

(16) Michael Siegel. "New Study Demonstrates How Conflicts of Interest with Big Pharma Influence Reporting of the Effectiveness of Smoking Cessation Drug Treatment." The Rest of the Story: Tobacco News Analysis and Commentary. April 3, 2009.

http://tobaccoanalysis.blogspot.com/2009/04/new-study-demonstrates-how-conflicts-of.html

Dear Linda, let me make sure I don't misunderstand you:

98% of smokers who put in a good-faith effort to quit smoking, by going out of their way to use patch and gum treatments, combined with sheer dint of will, FAIL to reach a state of abstinence … and this is evidence in favor of the non-addictiveness of cigarette-smoking?

I'm stumped,

Brian

It's evidence that nicotine is not the reason for smoking and is not a source of addiction. If all that a smoker wanted out of a cigarette was the nicotine, the patches and gums would provide it. The "addiction" would then be slaked with no need, and no desire, for an actual cigarette. So it has to be something else. And that's perhaps the habit of smoking– the physical act itself. Which may, in fact, explain why the e-cigarettes, even those w/o nicotine, are proving to be far more "helpful" than patches and gums. Though the Healthists are out to ban them. This is not to say nicotine doesn't have an effect; just to say it's not an addiction.

I'm not sure focusing in on nicotine itself is a useful zooming-in. The problem is cigarette-smoking, not nicotine-consumption. It's the cigarette smoking (and not the nicotine per se) that leads to things like lung cancer, etc. So as long as cigarette-smoking, construed broadly, is meaningfully addictive, then that's the level of analysis relevant to these type of arguments. At least that's as well as I can figure it out. Thanks again, Linda, for your contributions.

Brian, VERY well put: <b>"If smoking were damaging to one’s own health only — with no ill-effect on anyone else — then I would feel very differently. People have a right to self-harm. Or, more than that, to decide what constitutes (self) harm … many smokers would say that, on balance, a life lived with cigarettes increases their subjective well-being, even if it may shorten their years on Earth. In some cases this may be self-delusion, radical discounting of future pain, or behavior-justification; but I expect in many cases it’s true — that is, subjectively true for the smoker making the argument."</b>

Your point about "the order of questions" is also insightful: these antismoking surveys/studies/polls are VERY carefully designed to give the "correct" answers. Order of questions and careful selection of words as well as the general "intro" to the questions are all VERY important in influencing results to create what the researcher wants to create for either more grant money or for their own misguided idealism.

I'd like to add that Audrey's points are very strong. Check on her facts and arguments and you'll find that they're a lot more sound than what you hear from the other side.

Re monetary costs:Google "slipperiness of mutating word definitions" and read my "Taxes, Social Costs, and the MSA" to see my article on that. Even 10 years ago smokers were supporting the health care costs of nonsmokers, and it's MUCH more true today with the enormously higher taxes.

Re Linda/addiction/nicotine/smoking: Linda's point is valid. According to the Antismokers "nicotine is the most addictive drug in the world" etc. But in reality it's the "enjoyment of smoking" — the combination of the physical/psychological aspects of the action itself, ALONG WITH the stimulant effect of nicotine, that make smoking "addictive."

Also re addiction: Simply asking people is fairly worthless as their answers will be so enormously tainted by the psychological mileau of the last 20 years or so. If you asked a random sample of smokers if they were "addicted" in 1970 you might have gotten a 5 or 10% "yes" response. Today you'd probably get a 50%+ response. Heh… you also need to realize that for smokers the response of "Can't quit, I'm addicted." is simply a helluvan easy way out of an argument with someone trying to tell you that you should quit.

Final suggestion: to get a better sense of just how extensively we are lied to about the science promoting bans, Google "V.Gen5H" and read "The Lies Behind The Smoking Bans" there. You may be surprised!

Michael J. McFadden,

Author of "Dissecting Antismokers' Brains"

Hi Michael — thank you for your additions.

I read your piece on "Taxes…" and thanks for suggesting it. As I've been saying in earlier comments, I am prepared to accept as plausible arguments to this effect: that smokers burden the tax system LESS than non-smokers due to their habit of dying early. I can buy that that might be true. In order to take a hard stand on this point, though, I'd have to sift through the relevant evidence myself. And there's a lot of relevant evidence. As your article makes clear, there are very many variables that could be factored into calculations of "social cost" — and it seems like you get different answers depending upon whom you ask. Since I'm all too aware of how easy it is to lie with statistics, I tend to be very cautious about accepting the "findings" of any large-scale calculation matrix: too many numbers are easily suppressed or forgotten, or inflated, or estimated, or ignored, or made up, etc., irrespective of the ideological leanings of the number-cruncher. I guess that's why I do experiments, and stay away from "social science."

Re: Linda's argument about addiction. I guess I just don't see the point. Smoking cigarettes is clearly addictive for a huge number people–on any meaningful definition of the term. Whether the mechanism of addiction is nicotine, or is rather some combination of chemical, psychological, social, and habitual factors, is totally irrelevant. Most addictions are a combination of those factors. They're still addictions. And smoking is addictive. Insofar as being addicted to some substance (through whatever mechanism) plays tricks on the mind–by, for example, exaggerating the natural human propensity to discount future suffering, for oneself and others–then I think that's sufficient for tempering "free choice" arguments.

But even so, I don't think smoking is irrational per se, and I don't think stigmatization is (in general) a good thing. I could respect a smoker who said the following. "Yes, I accept that smoking is addictive, and that addictions affect the mind in ways which make future suffering seem less viscerally important and worth preventing. I also accept that smoking dramatically increases my chances of getting lung cancer or suffering from a whole range of other maladies. I accept that smoking may shorten my life. I accept that when I'm old, I may wish that I hadn't smoked when I was younger. But look. Lots of things in life are risky — yet wonderful. Driving is risky, but I love to drive. I could die at any minute in a car crash. Smoking is risky, but so are many things I happily do. I do these things knowing that I'd prefer a life of wonderful riskiness to a life of vanilla caution. Living is what you do in each present moment. And while I'm alive, I want to partake in the joys of smoking."

Well, OK. I wouldn't think like this, or feel the same way; but I can't fault this person for her reasoning; and I don't think slathering on social stigma is a useful response.

Those are my thoughts for now. Thank you again for joining the discussion, and for sharing some of your own work.

Best,

Brian

And thank you for a thoughtful response Brian. I had missed it originally as I post on a number of boards in the course of a day and generally just check the "new comments" at the bottom and miss intermediary responses mixed in with older comments further up. Generally you will find me responding at the bottom, along with needed quotes.

🙂

MJM

The argument about "addiction" v the pleasure principle or mere habit could go on interminably. Let me just say that I don't concede my point. And add that tonight's network news had a feature on how foods containing fat are addictive. (No scare quotes implied: just flat out addictive.) Adding that they stimulate the same centers of the brain that are stimulated by marijuana and (therefore) trigger irrational repetition. (And of course lead to very expensive diseases.) And so we go on to medicalize– and soon criminalize… life.

On the other subject– the wholesale legalization of stigma–here's an article you should look at. If you like you can follow the links to the full (30 page) report:

http://www.thefreesociety.org/Issues/Smoking/important-questions-about-the-state-of-civil-liberties-in-britain

Hi again Linda,

Glad to be having this conversation with you. You're right that our "addiction" conversation could wander on without getting us too far. I think it's clear that addiction is a combination of many factors, including chemical, psychological, social, and habitual; and if that's what you think, too, then we don't disagree.

Your point about fats being addictive … what is it? I'd need to look at the evidence, but I can see no a priori reason to assume that fats are not addictive. Whether they are or aren't, or are to a degree, is (so far as we can fairly pin it down) a matter of fact. What we do with that fact, by, e.g., "medicalizing" people who are addicted to fatty foods, is a separate question — and I can guess how you'd answer it. But I'll need to take a look at the studies on fat's being addictive so that I may judge them on their scientific merits. Do you happen to have a link to the relevant research?

Best,

Brian

No, it was just something I saw on television last night though there must be a recent, and googleable, "study." . But it's a theory that's been being pushed for quite a while– the while in which "obesity" has suddenly become a Public Health obsession (as a cause of expensive disease), and the while during which opportunists (like John Banzaf) have been trying to sue MacDonald's. This is just another bit of agenda driven science. If fat were truly an "addictive' substance, then fat was always an addictive substance, even back when Americans as a lot were thin and fit and when just as many hamburgers and Oreos and potato chips and Good Humors were around.

There's also been a lot of news about the addictiveness of the internet, Blackberries, and social media. We now also have sex "addicts," shopaholics, etc. My point isn't that foods containing fat are really addictive, my point is that anything can be said to be addictive.

Anything that's pleasurable can be shown to hit the pleasure targets of the brain and then, and therefore, be said to be addictive. Then, too, there's such a thing as an addictive personality– people who can, in a manner of speaking, get hooked on any object, action, or substance which doesn't mean the action/object/substance is "addictive."

However, back to food. One of the first "food is addictive" theorists was David Kessler, ex FDA chief, who clearly himself has a psychological problem that he's dodging by attempting to project it onto the world: the evil food industry, and onto the food itself. It's horribly and rather hilariously transparent. . I can't find the original article (NY Times?) in which he confessed this but there's a funny scathing article in the Weekly Standard and another in Reason:

http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/016/798lxisv.asp?pg=2

http://reason.com/blog/2009/04/30/david-kessler-goes-dumpster-di

Hi, Linda. Ok, "addictive" is a slippery word (so are most words). Let's leave it aside for a second.

Do you think that obesity in the U.S. is not a problem, and a growing one? Do you think that it is not the case that more and more people are becoming more and more overweight? Do you think that it is not the case that this being-overweight is a serious threat to people's health and well being? Do you think that it is not the case that very many people who are morbidly overweight really, really wish they could lose weight, but can't seem to do so, despite their best efforts?

Do you think it is not the case that there is a serious mismatch between (a) our evolved urges concerning food (namely the strong desire to eat fats and sugars whenever they're available, since such substances, in moderation, were, in the environment of evolutionary adaptation, both very good for our ancestors' survival and relatively hard to get) and (b) our contemporary environment, in which it is ever-easier and cheaper to consume massive quantities of health-destroying foods? Do you think that it is not the case that it was relatively easier, cost-effective, and time-permitting for a majority of Americans to eat healthier foods back when they, "as a lot," were thin and fit?

I hope you will say that you don't think these are "not" the case. And if you do say that, who cares about the semantics of addiction in the face of all those concerns? But let's settle on a reasonable definition just in case. Let's just define a substance (x) as being addictive for person (P) just in case P finds x very, very difficult to resist consuming, even in the face of clear knowledge that x is harmful, and even when P desires not to consume x, at least to the extent that P regularly does, in light of P's longer term goals for P. Aren't cigarettes addictive in this sense for very many smokers? And aren't fatty foods addictive in this sense for very many people, and especially overweight people? And isn't this a very reasonable definition of "addictive"?

Best,

Brian

Hi Brian,

I think we're still playing with the meaning of "addictive." (I'll let Michael M. respond to the Orwellian tricks with words but, in general, if we all start playing Humpty Dumpty–"When I use a word it means exactly what I choose it to mean. Neither more nor less"– we will shortly arrive at Babel.) Medically, "addictive" once– and not long ago– had a distinct meaning.

Yes, more people are more overweight now than 30 or 40 years ago. Being terribly overweight is probably a health risk, and in terms of "well-being" probably a social and economic handicap. But neither of those things means that food in itself is an addictive substance. Food was always food and addictive was always addictive (opium, for example) and people were always people and it was always just as possible to ravage a box of Oreos in 1987 or 1963 as it is in the present day. If Oreos are "addictive."

And WHY people are fatter may be different for each person. Genetics, psychology, environment, even fashion. (At various times in history, fat was a sign of beauty and at others, a sign of wealth. Nor is that ancient history. In Diamond Jim Brady's day, the rich ate like porkers; now they're anorexic. Food didn't change, people didn't change; it was merely a change in fashion.) Then there's depression, frustration, rejection, sedentary working, or having quit smoking. None of these have anything to do with any helpless addiction to certain food, no matter how you define addiction.

As for genetic/ evolutionary causes of obesity, some anthropologist (name evades me.. was it Diamond?) devoted one of his books to showing how different peoples evolved different kinds of chemistries, with some turning almost all carbs into fat. Pacific Islanders were such, which is why, with the introduction of 20th century food, they notably ballooned. Or so says…Diamond? But again, that has absolutely nothing to do with food or its inherent "addictiveness." OTOH, some people never get fat and metabolize differently.

Are some people prone to compulsive behavior? Even self-destructive compulsive behavior? Absolutely yes. But that's something within their brains and also, in some cases, their personal physiology. Some have a fatal attraction to alcohol. (Do we then ban alcohol? Seems that was tried.) Some are compulsively drawn to romance shoes. (Do we then ban shoes or deface them with dirty labels?)

The question, seems to me, is larger than what you state. The question is: what should society try to DO? or how and in what ways should society intervene? I maintain that interventions, once they become coercive, punitive, demeaning, or generally hectoring inevitably backfire and merely cause harm, not only to the people they're intended to "help" but to society at large. So as far as I'm concerned, if Mary Lou Cupcake wants to eat herself to death– or to a job in the circus–that's strictly up to her, And if she doesn't "want" to do it but anyway does it? Recommend a psychiatrist, recommend a nutritionist and then…it's up to her. You simply can't legislate human behavior, or human psychology. And who gets to choose what behaviors are "correct"? and at any given time? (In "Reefer Madness" the good, wholesome teens were the ones who smoked Camels.)

Brian,

Sorry to come late to this discussion. My first reaction when I saw the title was, "I'm going to agree with this", which is why I didn't bother to look at it. But (like you) I'm intrigued by Dmitri Pisartchik's counter-argument about the role these adverts play in increasing public awareness of the risks. I wouldn't buy this argument if it was just a question of improving public knowledge sui generis (why pick on the dangers of smoking?), but it does seem plausible to me that what might be counter-productive in the short term and on an individual level might nevertheless be effective in the longer term and at the societal level. I don't have statistics, but I hope that at least smoking bans are effective in reducing smoking, and it may well be that they are at least partially a result of the increased awareness that negative advertising has generated.

Two questions then spring to mind.

The first is the one you raised in response to Dmitri: can this kind of argumentation justify the negative impact on individual smokers? (Not to mention non-smokers who just receive an unnecessary and irrelevant increase in their stress levels.) It's a good question, but the answer very much depends upon one's ethical framework. As a utilitarian I would say yet it can in principle (the end can justify the means), but there may be good rule utilitarian grounds for saying that it doesn't in this case. I don't really have a clear view on this.

The second is whether there aren't *better* ways to achieve the positive, long-term/societal result without the negative, short-term/individual impact, and this question could lead to a more general one: under what circumstances should we focus on risks, dangers and negative impacts at all? Adherents of the Law of Attraction will presumably say never, but that is clearly a recipe for walking in front of a truck. But positive visualisations *are* important, so maybe the real policy conclusion from all this is that we (and governments) should make more effort to imagine a world without smoking, and raise awareness of *that possibility*. In other words, what do we want smokers to do *instead* of smoking?

Hi Peter,

I appreciate your thoughts here. I'll add something just on your final point — visualizing the positive instead of stigmatizing the negative. Roughly I think that's the right approach across a wide range of cases. I would be curious to see what it would look like to promote such a policy in the case of cigarette-smoking in particular. I agree with you it's worth considering!

Best,

Brian

What has happened over the last 30 years is the deliberate distortion of the English language in various and sundry ways to make it more compliant with the needs of political activists, with the strongest case in point being the antismoking activists.

Thus we see Obama declaring that the 150% tax increase he pushed and signed for a month or two after being in office was either (A) not really a tax, or (B) not a tax on actual "people" but just on what I guess would be called "vermin" (smokers) as per Sir George Godber's reference to them as an infestation of head lice:

http://pro-choicesmokingdoctor.blogspot.com/2009/07/obama-in-bare-faced-lie.html

And we see heads of antismoking organizations declaring that smoking bans are not actually smoking bans since smokers are still "free" to hide in their houses and smoke. (Shawn Cox of the KY ACS: "This is not a smoking ban. This is a comprehensive, indoor clean-air effort.")

And we see "employees" redefined as: "anyone who provides a service to another with OR WITHOUT compensation" (emphasis mine) while "employer" is simultaneously defined as "anyone who employs" such people.

And of course we've seen "children" redefined to anyone under 21 or so as we attempt to keep tobacco and alcohol out of the hands of "children" by raising taxes on them and imposing other sorts of limitations.

We've seen attempts to rededefine "child abuse" to include smoking in a home with a 17 year old present, or perhaps even in an apartment building where a 17 year old might be visiting their great-grandmom. We've seen general cigarette taxes redefined as "user-fees," "global threat" redefined as changing the bedding of a smoker, the permission to smoke outdoors on campuses redefined as "enabling drug usage," and "child endangerment" redefined in the "no safe level" world so that allowing your teen to step outside in daylight hours to pick up the mail from the mailbox might qualify Remember that giant Melanoma Maker in the sky, and remember that sunscreen etc only provides "partial protection.)