Blog Authors: Julian Savulescu, Brian D. Earp, Jim A.C. Everett, Nadira Faber, and Guy Kahane

This blog reports on the paper, Kahane G, Everett J, Earp BD, Caviola L, Faber N, Crockett MJ, Savulescu J, Beyond Sacrificial Harm: A Two Dimensional Model of Utilitarian Decision-Making, Psychological Review [open access]

How Utilitarian are you? Answer these 9 questions to find out…

If you enjoyed taking our ‘How Utilitarian Are You?’ test, read our new blog post discussing how we developed it, what it shows, and why it’s important

Utilitarianism is one of the oldest and most influential theories about what the right thing to do is. It says that the right act is the one which has the best consequences. In the first formulation by Jeremy Bentham, hedonistic utilitarianism, the right act is the one which maximises happiness and minimises suffering. Richard Hare and Peter Singer made preference utilitarianism famous: the right act is the one which maximises satisfaction of preferences.

Utilitarianism was a novel egalitarian theory when it was developed in the 1700s. It was a radical departure from authoritarian, aristocratic or otherwise hierarchical ways of thinking, positing that each person’s happiness and suffering was to count the same. In stark contrast to the social norms of the day, utilitarianism held that the happiness of the pauper is just as important as the happiness of the Prince or the Pope.

Utilitarianism has fallen into disrepute. It is now equated with Machiavellianism: the end justifies the means, whatever those ends may be. It is also seen as coldly calculating, or else simplistically pragmatic. The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche described it as a morality appropriate for shop keepers. Recently it has even been portrayed a doctrine for psychopaths. Pope Paul II put it succinctly in 1995:

“Utilitarianism is a civilization of production and of use, a civilization of ‘things’ and not of ‘persons,’ a civilization in which persons are used in the same way as things are used.”

Part of the reason for these negative representations is that most people equate utilitarianism with killing an innocent person to save others. Perhaps they have heard of those famously contrived “trolley problems” (now circulating online as humorous memes) where some unsuspecting worker or bystander gets run over by a train to avoid the same fate for five other workers. The most extreme version of this kind of trade-off is the survival lottery – killing one healthy person to extract their organs to save five others dying of organ failure.

All of that sounds rather dire. And to an extent, the reputation is deserved. Part of utilitarianism really does involve the willingness to sacrifice one or more innocent people, albeit in very specific circumstances where this is truly necessary to save a greater number of other innocent people, and where doing this will genuinely make the world better all things considered—it’s not just about numbers. (For a sympathetic discussion of the morality of killing one to save the many, see this blog post and the ‘Epidemic Cartoon‘ it inspired .)This element can be called instrumental or sacrificial harm.

When psychologists try to study utilitarianism, they focus almost exclusively on this issue of instrumental harm—asking people whether, for example, they would push a large man to his death in order to save five others from a runaway train. It is therefore not so surprising that psychopaths are the group of people that has been most consistently associated with utilitarianism in recent psychology, leading some to conclude that ‘utilitarians are not nice people’.

But that is only half the story.

There are two other features of utilitarianism that are often neglected. First, it compels us to do as much good as we can in the world—a much more positively oriented aim—while treating each of us in exactly the same way. So when I ask, “What is the right thing for me to do?”, my own wellbeing counts no more (or less) than anyone else’s. So, if I could give a kidney and save someone else’s life without putting my own life at equal or greater risk, I should give a kidney. This is very demanding. And if I do it, admirable—maybe saintly.

This is impartial beneficence: the idea that we should help others as much as we can from a completely impartial perspective, giving no special weight to ourselves or to our family or friends. While some might admire a Mother Theresa for behaving this way, others are very resistant to this aspect that can also come across as Spock-like or unemotional. Someone who doesn’t treat their own friends or family any differently from others might even seem a little suspicious, no matter how much good they do in the wider world.

Unsurprisingly, then, most people are not utilitarians. And even those who are fall short of its strictest demands. No one is a perfect utilitarian.

The second neglected feature of utilitarianism is that it draws no distinction between what we do versus fail to do. That is, it rejects the moral distinction between acts and omissions. Ordinary psychology involves a causal sense of responsibility: we intuitively believe we are responsible for the consequences of what we do, but not for what we omit or fail to do, even when the consequences of both are equally foreseeable and avoidable. If I drop a rock on you and kill you, I am guilty of murder. If I see a rock about to fall on you, and don’t warn you, I am guilty of nothing in law.

Utilitarians reject this distinction: what is important for them is nothing more or less than that the world has greatest amount of happiness or wellbeing (or preference satisfaction).

The rejection of the acts-omission distinction makes utilitarianism even more demanding because there many simple things we fail to do, as a result of which many people suffer or die. Giving a small amount of money to an effective charity can save literally hundreds of lives. Most of us don’t give to such charities.

This aspect of utilitarianism requires great sacrifices, perhaps greater than called for by any religion or other moral theory. It requires that people not only be Good Samaritans, but Splendid Samaritans, as Judith Jarvis Thomson once put it (in another context).

These two aspects – instrumental harm and impartial beneficence – can pull in opposite directions, psychologically. We previously showed that people higher in psychopathic tendencies are more willing to inflict instrumental harm, but they are lower on impartial beneficence. So, while they might superficially seem ‘utilitarian’ if you look just at the negative dimension, they are clearly not utilitarians when you look at the full picture.

Now, in an article in Psychological Review, which has been featured in APA Spotlight, we describe a new scale for measuring how utilitarian people are that takes into consideration both dimensions of utilitarian philosophy: the Oxford Utilitarianism Scale. It takes a couple of minutes to fill out and appears at the beginning of this blog.

Maybe you think it is ok or even right to be non-utilitarian because it is too demanding, requiring you to make sacrifices to impartially promote the welfare of others, even if they are total strangers. But then, Peter Singer, the world’s most famous utilitarian once said, “Maybe morality should be demanding.”

Featured article

Kahane, G*., Everett, J.A.C.*, Earp, B.D., Caviola, L., Faber, N.S., Crockett, M.J., & Savulescu, J. (2018). Beyond sacrificial harm: A two-dimensional model of utilitarian psychology. Psychological Review. Available online ahead of print at http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-57422-001

Additional references

Harris, J. (1975). The survival lottery. Philosophy, 50(191), 81-87. Available at http://history.as.uky.edu/sites/default/files/The%20Survival%20Lottery%20-%20John%20Harris.pdf

Kahane, G., Everett, J. A., Earp, B. D., Farias, M., & Savulescu, J. (2015). ‘Utilitarian’ judgments in sacrificial moral dilemmas do not reflect impartial concern for the greater good. Cognition, 134, 193-209. Available at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010027714002054

Parens, E. (2018). Utilitarianism’s missing dimensions. Quillette. Available at http://quillette.com/2018/01/03/utilitarianisms-missing-dimensions/

Savulescu, J. (2014). Why I am not a utilitarian. Practical Ethics. Available at https://blog.practicalethics.ox.ac.uk/2014/11/why-i-am-not-a-utilitarian/

Singer, P. (1972). Famine, affluence, and morality. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 229-243. Available from http://philosophyfaculty.ucsd.edu/faculty/rarneson/Singeressayspring1972.pdf

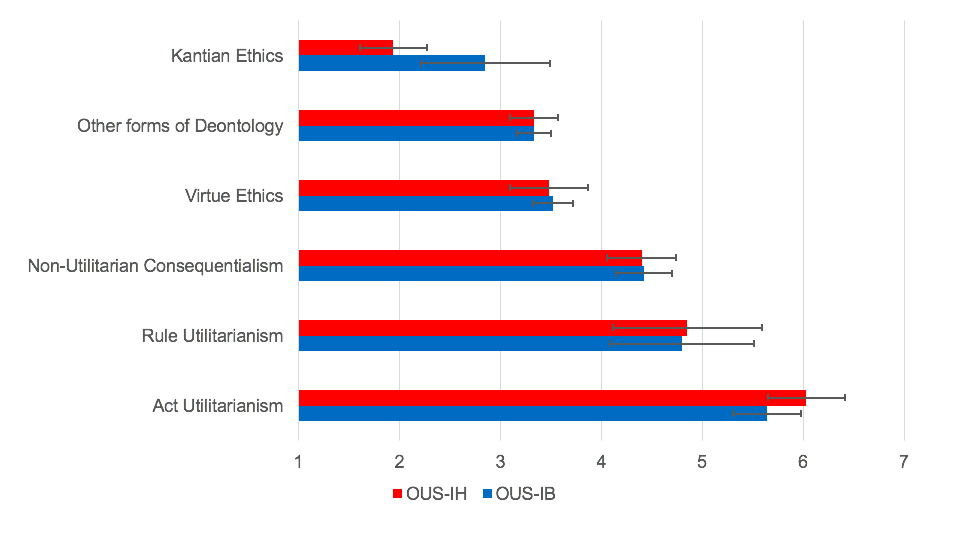

The graph at the bottom of this post is a little puzzling without a description. I know from the paper that what it’s showing are the scores of a sample of philosophers grouped by their self-reported schools of ethics, but on its own it’s easy to read it as saying that any Kantian would fall in this range, any other deontologist would fall in this one, any virtue ethicist in this one, etc. In other words, it looks like it’s giving score ranges for the schools themselves, rather than for the particular participants who described themselves as members of those schools. And if you do misinterpret it that way (as I did at first – I read this post before the paper), it looks like it’s being claimed that the scales don’t just make it possible to distinguish utilitarians from non-utilitarians, but also to distinguish particular kinds of non-utilitarians from each other.

My views are Kantian, and I struggled to settle on answers to some of the questions in the mini test because (to get embarrassingly Kantian for a second) I had to imagine what my maxims would be were I in the scenarios described. The test was almost presupposing a third-personal way of approaching moral dilemmas, which a utilitarian might find comfortable but at least my sort of Kantian wouldn’t. That’s fine, of course, since it is a test of how utilitarian you judgements are. But I think where I fell within the range of non-utilitarian scores (in the 32-49 bracket) had more to do with how I was imagining my practical reasoning in the scenarios than with the fact my way of approaching those scenarios was Kantian rather than, say, virtue ethical.

I struggled with settling on an answer for some of the questions because I needed a context to work with. Somewhat agree and disagree became my default answers on several questions so I wasn’t surprised when I fell into the non-utilitarian bracket of 21-31.

I can confirm, without surprise, that my very low score could be used as a sort of low-grade validation of your test.

But I don’t think that it entitles you to conclude (and I see no arguments to demonstrate that) I think it is ok or even right to be non-utilitarian because it is too demanding, requiring you to make sacrifices to impartially promote the welfare of others, even if they are total strangers.

Could I not have a whole host of other reasons for not becoming a convert to this version of moral philosophy?

Correction

I can confirm, without surprise, that my very low score could be used as a sort of low-grade validation of your test.

But I don’t think that it entitles you to conclude (and I see no arguments to demonstrate) that I think it is ok or even right to be non-utilitarian because it is too demanding, requiring me to make sacrifices to impartially promote the welfare of others, even if they are total strangers.

Could I not have a whole host of other reasons for not becoming a convert to this version of moral philosophy?

I know that in certain situations I have and no doubt will make decisions that could be described as being utilitarian. However, the result of your survey classifies me as ‘not very utilitarian at all,’ which, given the extremely narrow descriptions and available answers to the ethical dilemmas posed, is correct. Of course, it is not a ‘correct’ description of me in the real world and is therefore not of any great interest or use.

I would also like to echo Anthony’s point about utilitarianism not being demanding. For sure, if I adhere to the simple ‘external’ reasons of utilitarianism it may mean I live a pretty straightened life and I may be required to give my life to save others, etc., all of which could be described as being ‘demanding’. I would not, however, describe it as being ‘morally’ demanding because moral decision-making requires, inter alia, ‘internal’ reasoning in a changing world which can be very demanding.

I got 29, but I thought that was a bit low. Basically I don’t think the test captures enough of the different contexts in which we make moral judgements. As an individual, making decisions at individual scale about things like looking after my family vs looking after others, I’m not much convinced by utilitarian arguments. As a citizen making assessments of different policy settings, I think utilitarian is very valuable. (Though I think this is most convincing at community/municipal/domestic level – I find arguments for global cosmopolitanism endlessly fascinating but (with some exceptions) generally unconvincing.)

So my bit of feedback would be that you could have some other flavours of questions in there, such as “when assessing possible national policies, evaluation of net costs and benefits should be the primary consideration.” Or similar.

But, echoing some of the other commenters here, also I think you’re too wedded to a particular path to/view of utilitarianism and its demands. The commentary reads a bit like a group-think product: too many similar perspectives and not enough intellectual diversity. Pope Francis, the Dalai Lama, Jain monks and would presumably object to your claims that utilitarianism is the tough mudder of moral theories, and that the only reason for rejecting it is because we nonutilitarians aren’t moral ironmen like you guys.

Comments are closed.