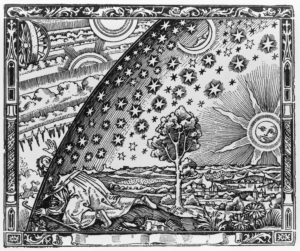

Provided my eyes are not withdrawn from that spectacle, of which they never tire; provided I may look upon the sun and the moon and gaze at the other planets; provided I may trace their risings and settings, their periods and the causes of their travelling faster or slower; provided I may behold all the stars that shine at night – some fixed, others not travelling far afield but circling within the same area; some suddenly shooting forth, and others dazzling the eye with scattered fire, as if they are falling, or gliding past with a long trail of blazing light; provided I can commune with these and, so far as humans may, associate with the divine, and provided I can keep my mind always directed upwards, striving for a vision of kindred things – what does it matter what ground I stand on?

Seneca, Consolation to Helvia, translated by C. D. N. Costa

Historically philosophy has developed into a theoretical discipline, mainly studied and practiced in academia and as such existing relatively distinctly from the broader cultural sphere, the public debate and the everyday lives of most people. Today there is, however, a revival of public interest in philosophy as an integrated part of ordinary life and a discipline that can provide wisdom on what constitutes a good and meaningful life and advice and practical instructions for achieving this.

A wave of self-help literature has washed in over western societies in recent decades in a response to the psychological unrest of our times. There is an anxiety in the age of the Anthropocene, caused by new and greater moral and existential uncertainties and related to the high complexity of the global and online modern world, the recognition of the growing existential risks in the future of humanity and the planet and to new insights and developments in science and technology that challenge conventional conceptions of what it means to be human and undermine the anthropocentric and humanistic world view. And this existential anxiety is accompanied by an increase in the interest in philosophical guidance and the demand for life-advice.

The renewed interest in philosophy not just as a study, but as a way of life has brought ancient philosophies to the fore, including that of Stoicism. Stoicism appears to respond effectively to the modern meaning crisis and the call for guidance for how to live a peaceful and meaningful life in a world of increasing complexity, change, uncertainty and existential danger. Researchers, philologists, public intellectuals and life-style specialists are today engaging enthusiastically in new interpretations and revisions of the classical Stoic ideas, which are released both in- and outside a scholarly context and in formats ranging from new translations of the foundational texts and substantial philosophical criticism and developments of the philosophy to life-guidance for lay persons in self-help literature, podcasts and blogs.

The appeal of the ancient philosophy to the modern individual is in some ways obvious. Stoicism responds to a fundamental human longing for existential emancipation. The basic human drive for survival, the desire for material goods, capital and status and immediate satisfaction of needs and desires in humans have always been accompanied by a wish for release from these evolutionary and biological forces, for renunciation and detachment, for peace, calm, deeper meaning and liberation from the repetitive life-form governed by survival and procreative instincts. The feeling of not being in control of one’s life, but rather a victim of external forces or some form of fate is also a common human experience. Stoicism recognises these fundamental existential experiences and conditions and the suffering they cause, which in itself can bring some consolation to the struggling modern individual. Moreover, it is practical and offers strategies and techniques for life-improvement, coping-mechanisms and thought experiments that can be used by anyone and have an immediate effect of relief.

At the same time, the revival of Stoicism is noticeable because it also goes against the grain of the self-help trend. Most theories and ideas in this field rely on a belief in autonomy and free will and encourage individuals to assume agency and take control over their lives, to proactively bring about change in order to increase happiness and wellbeing. Stoicism, however, entails a deterministic world-view. It explains humans as part of the cosmos and as conditioned and determined by events that are outside our control.

This determinism which is part of the cosmology of Stoicism is backed up by modern science and its explanation of the world in terms of physical laws. Just as all other components of the universe, humans are part of chains of causality, of cause and effect, that go back to the big bang (if not further) and as such already embedded in pre-determined developments. This recognition of determinism for some leads to relief and a sense of existential emancipation. But for many, this is a disturbing and unsettling insight. It challenges the common intuition and experience of having free will and being in control of one’s life which most self-help literature speaks to and can lead to feelings of existential imprisonment and discouragement.

Stoicism is not flawless, and it entails certain contradictions. It subscribes to a determinist world-view and at the same time stresses the importance of ethical behaviour and moral responsibly towards others, which implies a belief in autonomy. And as Martha Nussbaum has pointed out, aspects of it are outdated and should be revised in accordance with modern science and values. Even so, Stocisim resonates strongly in the modern culture. Much of it is already non-religious and as such fitting for secular times where the natural sciences are increasingly gaining authority in the explanation of the human being and the world.

It also has striking overlaps with the Eastern contemplative traditions and philosophies which have in recent years had a strong pull on the secular Western world. Buddhism and its westernised versions of mindfulness are also life philosophies with prominent practical dimensions. As in Stoicism, the focus is on equanimity, detachment and increased wellbeing rather than on happiness as such. And both emphasise the impermanence of everything – of joy and sorrow, pleasure and pain, of all phenomena in human life and the natural world. They are monist philosophies and give a holistic description of the world, stressing the connection between humans and other living beings, nature and the cosmos. This explanation of humans as part of the cosmos and connected to nature – rather than as distinct from these – go well with the modern climate awareness and criticisms of the objectification and human instrumentalisation of nature.

Stoicism has potential for being a foundational component of the ethics and existential outlook of our present and future. The ancient philosophy sheds light on how determinism can lead to existential liberation and relief as it offers the insight that resisting and fighting whatever unpleasant things happen to us only lead to disappointment, frustration and suffering; and while we do not have control of our lives or its events, we do have freedom to relate differently to what happens to us – that is, to change our judgements of our experiences and our evaluations of the events we form part of.

This granting of an attitudinal freedom is obviously not coherent with a strictly determinist world view. But it may be precisely this preservation of agency in terms of how we relate and respond psychologically and emotionally to the determined reality that makes Stoicism so broadly acceptable and highly appealing today; more precisely, its encouragement to calmly and with equanimity accept the unfolding of reality, to observe with curiosity and awe the developments and causal chains we form part of and their and our own embeddedness in a greater cosmological context, to embrace and even appreciate the uncertainty and mysteries rather than resisting them, and to lean into, as it were, and participate in reality with an empathetic and ethically responsible mindset.

This blogpost is based on a chapter in a forthcoming publication of a new Danish translation of Seneca’s letter of consolation to his mother Helvia and general introduction to Stoicism. Mette Høeg and Susanne Høeg: Seneca. Trøsteskrift til min mor Helvia (Klim; 2023).

Great

I am stoic in the face of homelessness. As I sit in the morning sun here in Boorowa, some 90 minutes drive north of Canberra, I adopt the philosophical mindset when temporarily finding myself camping under a vacant showground shed out of town.

Yes, I lost my job at the Australian National University. And with that went my financial stability and social identity.

Next, the contract work dried up. Offers stopped coming. The rent fell into arrears and soon enough I was asked to pack up my book lined apartment.

Fortunately the mild summer mornings allowed me to load the small removal van, all on my own, without overheating.

I hid for the most part my great need with this slide down the social pole.

One friend lent me $500 after stopping at the apartment just before the move. It was hard for him to ignore I was eating carrots and bread.

After the 6th visit to the social security office, I was deemed ineligible for any welfare support. It was a blow to my plans to stave off deeper poverty, hunger and the need to visit the pawnbroker with my laptop; the same laptop where my future income was being mapped out.

Another friend lent me his van, but not his labour. I was happy with that, knowing there was days of sorting, boxing, carrying, driving and unloading ahead. It would be therapy for me alone. For him it would be a chore.

It’s been over a week now. I have all my books, the same books I unsuccessfully tried to sell to book dealers in Canberra as a collection, in cheap country storage.

I’ve slept out under the stars, secretly in the storage shed a few nights and now out at the showgrounds.

In the little town of Boorowa I meet locals. I test there acceptance of me being neither a visitor, nor a local. I explain I am looking for work, albeit with immediate start and cash payment at the end of the day.

With my car sold months ago, I walk or cycle through town. I inhabit public spaces, recharge my phone in cafes, pubs or picnic shelters in parks where electricity is provided.

I talk of opening a little bookshop to interested locals who want to chat, knowing most are not likely to be my customers.

Late in the afternoon I go back to my little shed with discount bread and fruit. I call the old tan thoroughbred to the fence scratch her nose and feed her some fresh grass and a piece of my fruit.

The future will come. It will provide for me. It gave me clear skies and stars last night. It gave me a passing truck driver for a unguarded conversation last night. And it gave me this great article to read on my phone this morning.

I can hear the birds. My belly is full. More people know my name. And I have a little cash in my pocket.

Let’s see what comes…

A moving account of your stoicism and how fickle ones finances can be. You have the right attitude and I admire your positive attitude.

Hasmukh Shah.

I really enjoyed this read and look forward to more. I can’t remember how I landed here which, I must say, makes it a tad more special. However, as I often do, I read the first lines a few days ago and got distracted.

Today, while on my commute, I was about to start watching last night’s AFC Championship (NFL) when I realised I wouldn’t manage to connect my headphones to my phone because they are synced with my laptop, in my backpack. In the end, I decided to finish reading this before addressing the issue. I guess I needed something more enlightening than American Football.

mulberries

Comments are closed.