The agency that regulates fertility treatment and embryo research in the UK, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), has asked for public views on two possible new forms of fertility treatment that promise to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases to children. These diseases can be extremely severe, leading to (among other things) diabetes, deafness, progressive blindness, seizures, dementia, muscular dystrophy, and death.

How do mitochondrial diseases occur? Most people know that a human cell has DNA in its nucleus that contains the vast majority of the 20-25,000 protein-coding genes constituting the human genome. It is less well known that a human cell also contains additional genetic material, stored in small, energy-producing packets called mitochondria that float in the cytoplasm within the cell membrane. Mitochondria – probably evolved from bacteria that developed a symbiotic relationship with their hosts – have their own membranes and, within them, circular strands of DNA: it’s called mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Human mtDNA contains 13 protein-coding genes. Because mitochondria are vital to the functioning of the human cell, mutations in mtDNA that cause mitochondrial dysfunction can result in mitochondrial diseases. Human sperm and eggs both contain mitochondria, but the sperm’s mitochondria are destroyed upon fertilisation, leaving only the mitochondria from the egg in a developing embryo. A child therefore inherits all its mtDNA from its maternal line, and it can also inherit genetic mutations in mtDNA and mitochondrial diseases from its mother.

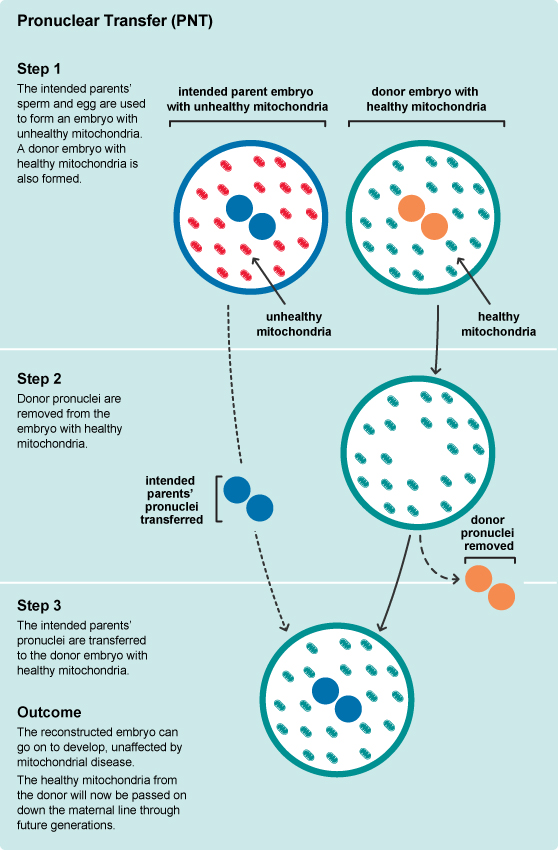

The fertility treatments in question promise to allow mothers and fathers to have their own biological children while preventing the transmission of mutations in mtDNA to their descendants. Two alternative methods of mitochondrial replacement may be used. In the first method, Maternal Spindle Transfer (MST), scientists transfer the nuclear DNA “spindle” from the mother’s egg cell which has mutated mitochondria into a donor egg with healthy mitochondria, then fertilise that egg by the father’s sperm in vitro and, finally, implant it in the mother’s uterus. In the second, known as pronucelar transfer (PNT), scientists fertilise both the mother’s egg with its mutated mitochondria and also a healthy donor egg in vitro, then transfer the nuclear DNA-containing material from the mother’s embryo into the “shell” of the donor embryo, before implanting it into the mother’s uterus. The treatments have been called “three parent IVF” by the popular press because the resulting child’s genetic inheritance has three sources – its nuclear DNA comes from its gestational mother and father, but its mitochondria, and thus its 13 protein-coding mtDNA genes, come from the donor.

The achievements of the researchers who have developed the treatments this far should be cause for celebration. Who would oppose scientific progress that promises to enable more women to give birth to healthy, happy children who are genetically related to them?

The Anscombe Bioethics Centre, a Catholic institute located here in Oxford (though not affiliated with Oxford University or its colleges), blasted my inbox a day or two ago with a panicky press release urging Christians and non-Christians to submit comments to the HFEA urgently opposing the proposed treatments. Here is how the centre’s Senior Research Fellow Dr Helen Watt describes the procedures:

Mitochondrial replacement has been called ‘3-parent IVF’, but only one technique being considered would in fact produce 3-parent babies. The other technique involves a form of cloning from an early IVF embryo, using a second embryo as a shell, to produce a third, clone embryo who might then be transferred to the womb of the first embryo’s mother to be born. The first and second embryo would be killed to create the third, clone embryo.

One technique would split genetic motherhood and give the child three genetic parents. The other technique would produce a child with no genetic parents: a child cloned instead from ‘spare parts’ harvested from earlier living embryos.

Both techniques would affect not only individuals conceived and born but also their descendants. Both should be urgently opposed, and the Anscombe Centre has produced a briefing which we hope will be helpful to those wishing to respond to the consultation.

Dr Watt is right that that “Both techniques would affect not only the individuals conceived but also their descendants,” but why should this be construed as a bad thing? The techniques are intended to affect these individuals and also their descendancts, precisely by ridding them of inheritable genetic mutations that would otherwise result in very nasty diseases!

Dr Watt’s and the Anscombe Bioethics Centre’s description of PNT as producing “clone” children with “no genetic parents” may sound quite horrifying – but it is scientifically inaccurate. There is no cloning involved in PNT. Cloning is, conceptually speaking, a kind of copying – you can’t clone a thing by simply moving it (or moving part of it) from one place to another. When you clone something, it must be at least conceptually possible (though it may not be technically possible) to leave the cloned thing intact. But this is clearly not the case for PNT, as the following diagram from the HFEA illustrates:

Dr Watt apparently calls the result of the procedure a “clone embryo” because it is produced by a technique similar to one used in cloning Dolly the Sheep (that is: replacing the nuclear material in an egg or embryo). But the mere use of such a technique does not necessarily make the result a clone, any more than the use of a scalpel would necessarily have made the result an appendectomy. The child produced from PNT would have two very obvious genetic parents who directly provided the vast majority of its DNA in the usual way – via their egg and sperm, as well as a donor mother who makes a very small but important genetic contribution to its heritage, by providing healthy mitochondria.

If concerns about cloning here are unjustified, should we instead oppose the new procedures because they would lead to a novel spectre of “three-parent babies”, and all kinds of potential identity disorders for the resulting children? No we should not! This is not just because there is no reason to think that children with three genetic parents should have any such difficulties, nor just because these children would only receive 0.1% of their genes from the donor, but also because “three-parent children” already exist, and studies have shown that they do not sufffer any psychological harm. Children are already born to surrogate mothers who have a genetically unrelated embryo implanted – this procedure is called gestational or IVF surrogacy and it has been happening since the 1980s. You might think that we should distinguish between this old procedure and the proposed new ones, because the child of a gestational surrogate mother receives no genetic inheritance from her. But this could not be further from the truth. Around ninety percent of the cells in the human body are not our own cells, but are microbial flora with which we live in a symbiotic relationship. They are essential to our survival and health, and they influence all sorts of our individual characteristics. The science of understanding these flora is in its infancy, but it has been shown that particular genetic variants of gut bacteria, for example, are inherited by children from their gestational mothers, and that there are identifiable genetic differences in flora between different ethnic groups (for example, Japanese people have seaweed-digesting flora in their gut that is not present in Americans). When we recognize the close similarity in form and in bodily function between mitochondria and bacteria, we should also recognize that there is about as much reason to call the child of a gestational surrogate a genetic “three-parent baby” as there is to call a PNI child the same thing. These children have more than two sources for their genetic inheritance. So what?

As the Anscombe Bioethics Centre rightly notes in its briefing paper: “This would be the first time UK scientists were permitted deliberately to engineer (in the sense of replacing) the genes that would be passed on to future generations … Now is the moment when we decide about the principle: Do we want genetically modified children?”

Let me put that question another way: Should potential mothers with mitochondrial diseases be enabled to bear their own healthy children, or should the rest of us restrict them to the following three options: bear no children, bear diseased children, or bear genetically unrelated children? It may be worth noting you can answer “yes” to the first question without also endorsing a complete free-for-all in human genetic engineering. The proposed treatments aim to prevent the transmission of serious diseases to future generations: if that’s not a good ethical reason for doing great medical science, I’ll eat my hat.

Do take a moment to report your views to the HFEA and let us know if you’ve done so in the comments. You can find more information at their web site here:

http://mitochondria.hfea.gov.uk/mitochondria/

and you can report your views here:

Thank you Simon, for the post and the links.

I’ve reported my views (which coincide with yours) . The problem of course, is that this type of opinion-seeking is wide open to lobbies who could organise thousands of responses, whether the “right” or “wrong” ones…..

Hello Anthony, thank you for your comment, I am delighted to hear that you are the first reader to make a submission to the HFEA consultation. You’re right about the lobbies, which is why those without vested interests and with genuinely open and inquiring minds also have a duty to contribute!

PS I’ve made my own submission, for whatever that’s worth.

That’s a very compelling rebuttal to the Anscombe Centre’s position. Some semi-critical thoughts:

You say PNT can’t be cloning because it is not conceptually possible to leave the original maternal embryo intact. Is that really conceptually impossible? I don’t know the biology very well, but it at least seems conceptually possible (if not technically possible) to split each pronucleus, leaving half of each in the original embryo and half in the new one, and still get healthy embryos – just as early-stage embryos can split to generate healthy twin embryos.

And as to the idea that you can’t clone something by simply moving it, consider the following (horrifying) thought experiment: You have a replication machine that can only work by taking a human heart and building up around it, from the genetic information contained within, a human body genetically identical to the ‘donor’s’ (kind of like the replication of Leeloo in The Fifth Element). I think it would be fair to describe ripping out my heart and putting it in the machine to create a replica of my body as a process of cloning (as well as murder; see two paragraphs down), and this process seems not too dissimilar from the process of PNT.

But whether or not PNT is a form of cloning is ultimately semantic. The real question is, do the Anscombe Centre’s reasons for opposing cloning also apply in the case of PNT, and if so, are they sound? To the former question, I think the answer is ‘yes’ – the standard Catholic line is that cloning is more wrong than regular IVF in large part because, unlike IVF, the embryo is formed by a process other than the natural union of sperm and egg. PNT is similarly not a simple union of sperm and egg. To the latter question, no, I do not think it is sound. It could first be pointed out that identical twins (assuming one thinks the twins are not identical to the original embryo) naturally emerged from a splitting process rather than a union, indicating that sperm and egg union is not the only natural process of embryo formation. And, moreover, one can cast doubt on the moral legitimacy of the appeal to nature – just because something is natural, does not make it good.

There is, though, another reason for opposing PNT that you don’t mention – it seems to involve the destruction of at least the pronuclei donor embryo, and arguably the mtDNA donor embryo as well, depending on how you define its existence conditions. Here, the further Catholic argument that embryos have moral status, crucially the right to life, can be used to oppose PNT. It is small consolation that the genetic material lives on – just as it’s not OK to kill me even if you plan to make a clone of me from my genetic material. But again, though there’s not enough space to do so here, we can cast doubt on the soundness of such opposition to embryo destruction.

Hi Owen, thanks. A few thoughts:

1) I agree that whether it’s cloning is ultimately semantic and ethically irrelevant. But words matter in public debate, and a scientific mischaracterization of PNT as cloning, if successfully promulgated, will almost certainly scare many people into opposing the procedure who wouldn’t have opposed it otherwise.

2) I didn’t say it’s conceptually impossible to clone embryos, but that with the process used in PNT it is conceptually mpossible to leave the original intact, and therefore it cannot be cloning. (The alternative process you describe of splitting the nucleus in half then growing back the missing halves would plausibly count as cloning). The imaginary removed heart case you describe is a form of cloning the rest of your body by producing a second copy of it (and therefore of cloning what in many contexts we would be willing to describe as “you”) – but not, notice, of cloning your heart, which has only been moved! In the case of PNT *nothing* is copied – the original pronuclei have only been moved to a new (and importantly different!) embryonic shell. That’s why PNT is transparently not cloning.

3) I agree with you that there are additional Catholic objections that I didn’t mention, and that they are unconvincing.

4) Philosophers are trained to focus on minutiae and to try to defend the most charitable possible reading of arguments that they may disagree with. That’s a sound means for trying to reach the truth about questions that are often very difficult. They even, perversely, seem to very often take great pleasure in this process. But I think philosophers, and especially practical ethicists, should sometimes step out of the seminar room and into the real world, which is to say that they ought to stop arguing and actually do something to change things. So much as I enjoy debating with you, I hope you will prioritize making your own submission to the HFEA above continuing the argument (which you are most welcome to continue)!

G. Owen Schaefer makes some good points, though I don’t think the cloning question is just semantic. Cloning an organism is copying an organism – whatever method one uses (there are several). No, the child of PNT would not be the genetic child of the couple – any more than Dolly the Sheep was the genetic offspring of the parents of the original sheep from which she was cloned.

The objection to cloning humans is not that it is not ‘natural’: there are natural accidents such as twinning and fusion of human embryos that no-one should be trying to replicate – not least because they kill/endanger human embryos. Rather, cloning humans is wrong because it not only ‘manufactures’ the child by a mechanical procedure (with all that tends to go with that in terms of manufacturer’s attitudes – quality control, discarding etc) but also – and this is new – deliberately deprives the child of true genetic parents.

With cloning by PNT things are even worse: instead of true genetic parents the embryo is formed from ‘spare parts’ taken from two deliberately destroyed embryos. This is even leaving aside the risk of new damage to the germline being created by the procedure itself – which would thus be damage for which those involved would be particularly responsible, having caused it quite directly. There’s a reason for those international statements about not engineering the germ-line.

We should bear in mind that the couple at risk of passing on mitochondrial disease do have the option of avoiding conception and perhaps choosing to adopt. Some favour conventional egg donation as at least safer than PNT, but splitting parenthood by conventional gamete donation is not innocuous: it creates problems for those conceived. Yes, we do sometimes hear reassuring voices (particularly from the social parents) but also more troubling voices (particularly from the offspring themselves). We cannot simply ignore reports like My Daddy’s Name is Donor, websites like anonymousus.org, books like Who Am I? Experiences of Donor Conception (and other material from Alexina McWhinnie) and so on – or see David Velleman on the family and a person’s sense of identity.

Hello Helen, thank you for stopping by to defend your point of view. A few thoughts:

1) You say that “cloning an organism is copying an organism”, yet insist that PNT is cloning. If I take an engine out of a mini and put it in the body of a jeep, I have neither cloned a mini nor a jeep. But that’s similar to the process used in PNT. What organism is copied in PNT?

2) You say that PNT is wrong partly because it deprives the child of two genetic parents. Whether that’s right or wrong, why is two such an important number? If two genetic parents are better than none, why aren’t three genetic parents even better? A child with three genetic parents would, indeed, have a special advantage: it would still have surviving genetic parent even if two of them died while it was young. The importance of genetic parents from your point of view seems to give you strong reason to support MST, which in your view does give a child three genetic parents.

3) You worry about unspecified and scientifically unproven germline risks, yet ignore scientifically-proven germline benefits (i.e. preventing the transmission of serious diseases). Any medical intervention (e.g. a new drug) has risks. That’s why we expect scientists and doctors to carefully assess risks both before and during use of a procedure. But we expect them to do a careful balancing of benefits and risks, not focus on risks alone and ignore potential benefits.

4) You write “We should bear in mind that the couple at risk of passing on mitochondrial disease do have the option of avoiding conception and perhaps choosing to adopt”. It is striking to me that you believe that *you and I* have a right to decide that the options that other women have are adequate, and that we have a right to prevent them from having child-bearing options they would clearly prefer.

5) In supporting your claims about the “problems” of splitting parenthood by conventional gamete donation, you point to various sources of unscientifically collected, anecdotal evidence. That’s the kind of evidence you can find on the web to support any number of quack miracle cures. But there have been proper, peer-reviewed longitudinal scientific studies on these issues (e.g Golombok, 2006), and they have failed to find evidence of any such problems.

Hello Simon – You’re welcome! A few thoughts in response.

(1) The individual copied is the couple’s affected embryo – an individual destroyed by the cloning process itself. Surely it’s possible to copy from an individual who will be dead by the time the copy is created: after all, Dolly herself was cloned, I think, from the tissue of an ewe who was dead before the process started. Moving pronuclei, like moving a nucleus, is one way of copying the organism from which/whom those parts are taken.

(2) Children need a sense of security and belonging – which is why they do better in practice with their biological and preferably married parents (there really is a lot of research on that, and I assure you it’s peer-reviewed!) It’s good for children to know that their parents are ‘fully’ their parents; not ‘partially’ their parents. Adults using donors will often try to tell their children that social parenthood is all that matters – but in fact in using donor gametes they tacitly admit that genetic links do matter to the fertile partner, or why are they using donors, not adopting a child who already exists? Something donor offspring will sometimes point out themselves – again, see books like Who Am I?

(3) The benefits of PNT and MST for actual human beings, who grow up and have children and grandchildren of their own, are certainly not scientifically proven. This really is unknown territory. The effects of inheriting faulty mitochondria are also extremely difficult to predict: some people are badly affected; some not at all. In any case, mitochondrial replacement is not a response to the needs of any existing patient. No patient is treated in either PNT or MST. PNT deliberately manufactures an affected embryo to be combined with a perfectly healthy embryo, killing both embryos, to create a third embryo via cloning. Rather a strange kind of medical treatment!

(4) Why should child production by laboratory means, using third parties, not be a fit subject for moral criticism and even legal intervention? Particularly if it involves cloning and killing the woman’s embryo every time, plus killing the embryo of a donor, not to mention risky and unnecessary effects on the germ-line – again, deliberately caused by third parties? See the description above: is it not straining things to pretend this is just like any woman deciding to have a baby?

(5) Well, no – there have certainly been peer reviewed studies of donor offspring which paint a less rosy picture – not only work by McWhinnie, whom I mentioned, but by others such as Turner and Coyle. Look them up and see for yourself – but also look up the anecdotal stuff, and the very large, though admittedly not peer reviewed, study My Daddy’s Name is Donor: real people describing real experiences. And look up Velleman: a philosopher reflecting on those experiences, and on the place of genetic parenthood in people’s lives.

Hi Helen, thank you again for responding, I’m glad for the opportunity to debate these important issues!

(1) You suggest that PNT is cloning because it involves copying of all three of an “embryo”, of an “individual” (i.e. a person), and of an “organism” from the would-be mother. These claims don’t appear to be scientifically compatible, if they are all supposed to refer to the same thing (e.g. because an embryo can naturally and spontaneously develop into identical twins, triplets and so on). But anyway, PNT is like taking the engine of a mini and putting it in the body of a jeep. Actually, a more precise analogy would be that it’s like taking the wiper blades from a jeep and putting them on a mini (replacing the mini’s own, faulty wiper blades), because more than 99.9% of the genome in the resulting embryo comes from the would-be parents, and less than 0.1% from the donor, in the form of her mtDNA. No copying whatsoever is performed by the scientists. It’s true that the biological process resulting in a child differs from car mechanics in this respect: the embryo then begins it’s process of natural cell division, which does produce copies of cells. But all the copies produced after PNT are of the modified embryonic cells, not of the original ones, which would have been afflicted by disease. That’s a perfectly ordinary process that also takes place in natural childbirth.

As far as I can see, there are only two embryos involved in PNT, not three – a donor embryo from which material is used and an embryo from the would-be parents which is treated by making a genetic modification to it in order that it can grow into a healthy child. But I don’t think a debate over embryonic ontology would be very productive, and anyway it’s irrelevant to the question at hand. Either the original embryo from the would-be parents survives the changes made to it, or there’s no attempt to copy the part of it that has not been moved into the resulting brand new embryo. Either way, there’s no copying, and no cloning!

(2) Your write that, “Children … do better in practice with their biological and preferably married parents”. This depends on the comparison class. The best research indicates that having a stable, loving home is what matters for children, rather than biology. Again, I don’t think anecdotal or non-peer-reviewed evidence has any place in a responsible discussion when there have been large, peer-reviewed, properly controlled, longitudinal studies that contradict it.

But I find it striking that, while holding this opinion that children do better with their biological parents, you have come out *against* techniques that would enable many would-be parents with mitochondrial diseases to share 99.9% of their genome with the children they seek to raise, advising instead that they “have the option of avoiding conception and perhaps choosing to adopt”, which you clearly regard as an inferior relationship.

Does receiving anything less than 100% of our genome from the parents who raise us not count? Then the natural mutations in our DNA must alienate all of us from our parents!

(3) The benefits of PNT and MST have been scientifically proven in animal studies. Of course they haven’t been proven in humans, because these techniques have not yet been fully tried on humans. That’s the same situation as for any new medical intervention seeking licensing. You write that “mitochondrial replacement is not a response to the needs of any existing patient”. That claim is false: it is a response to the needs of a woman with mitochondrial disease who wants to be the biological mother of a healthy child. If PNT and MST is “a strange kind of medical treatment” because it is not “a response to the needs of any existing patient”, then so is a woman’s taking folic acid supplements when planning to become pregnant, as advised by the NHS, for the benefit of the future child. Should the NHS stop issuing such advice, because it’s not “medical”?

(4) I don’t think the fact that the production of a child would be “by laboratory means” or “using third parties” gives anyone else a right to intervene, unless there’s very strong evidence (which does not exist) that the interests of the child itself or someone else would be harmed.

While I don’t accept your description of PNT, I do accept that the PNT process (though not MST) does involves the intentional destruction of a donor embryo, and if you think that day-old embryos have the same moral status as people, this will seem to you to license your moral and legal intervention. But if you really think that a day-old embryo has the same moral status as any other person, then you should surely not just oppose PNT, but also expensive medical treatments in general, as these resources could be much better directed into the life-saving prevention of natural spontaneous abortions, the number of which is at least half a million a year in the UK alone.

(5) Thank you for the references. Of course all the existing studies are of children with a much greater donor genetic inheritance than children of MST and PNT would have (50% vs less than 0.1%), and so those that suggest that donor children may have different outcomes may be beside the point here. But anyway, McWhinnie’s work mainly argues that children have a need to know the identify of their donors, which is not in dispute here. The other evidence you cite is essentially anecdotal, aside from Velleman’s philosophical work which is controversial and subject to dispute. So we have strong peer-review evidence from large longitudinal, controlled studies (e.g. Golombok) that donor offspring do just fine even with 50/50 split parenthood, and a ragtag assortment of weak evidence on the other side that not MST and PNT children, but traditional 50/50 donor children, many of whom were children of anonymous donors, have special difficulties. No impartial observer would, I think, even consider prohibiting MST and PNT based on such weak evidence of potential harm to children. Of course, it should also be remembered that the alternatives to MST and PNT for would-be parents with mitochondrial diseases would be these: traditional surrogacy, adoption, or bearing diseased children. Can you identify any evidence whatsoever to believe that MST or PNT would be worse for their children than any of these?

Hello Simon – thanks for this – just a few more points in response:

(1) A human person is a human organism – a biological being. Natural twinning doesn’t mean that the embryo who twins was never an individual human organism – any more than cloning from an adult means that the adult was never an individual human organism. That wouldn’t change if we imagine cloning from an adult somehow killed that adult (let’s say, by splitting him/her into billions of cells). I don’t think the car analogy helps us much, not least because a car is not a living whole, but something assembled by degrees (unlike an organism, it doesn’t construct e.g. its own chassis, actively arranging parts from the chassis, motor and electrics of previous cars). But in any case, it’s the couple’s original embryo as a living whole/organism, not that embryo’s pronuclei, that is copied/cloned.

Would you not accept that Dolly’s original was cloned? If transfer of a nucleus can achieve cloning (copying) of an organism, why not transfer of pronuclei? And would you not accept that an embryo is killed when that embryo’s pronuclei are harvested? This is surely the case, whether the pronuclei are taken from the donor embryo to make room for the transferred pronuclei or taken from the couple’s original embryo to be transferred to the now-gutted donor embryo. It’s the removing of the pronuclei that kills the embryo in both cases. True, the clone resulting will not be a perfect copy of the couple’s embryo – but then, neither was Dolly the Sheep a perfect copy of the sheep from whose tissue she was cloned…

(2) Have you seen the research cited at childtrends.org, or the Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect? I’m not, of course, saying that existing children should not be adopted, if they’re being abused or neglected; only that we should not be deliberately conceiving, as opposed to rescuing, children in parentally confused/deprived situations. Yes, natural parenthood allows for the random mutations you mention (which do not involve the entry of supplementary partial parents into the equation) – but the child should not be deliberately deprived of the standard, joint but otherwise undivided parental contributions.

(3) No, this is not the same as any new medical intervention, given that negative results of this intervention may reveal themselves only after several generations and/or go on ad infinitem: there’s no opportunity of trying out this on just a few people first (if we don’t count the embryos on whom we’re already lethally experimenting). Medical treatments do not normally affect the germ-line – or at least, they are not normally intended to affect it. And as for treating the intended social mother: how does cloning by PNT help the woman perform some physiological function? PNT doesn’t make the woman a genetic mother in any way – though she or any other woman to whom the embryo is transferred will, of course, be that embryo’s gestational mother. The intended social mother is already fertile and can already conceive and gestate her own, albeit affected embryo – an embryo deliberately destroyed by PNT! Does cloning from an embryo ‘treat’ the embryo it destroys? Clearly not – indeed, not even cloning from an adult who survived the process would treat that adult, since it would not help him/her ‘reproduce’ physiologically (as opposed to replicating him/herself in a completely novel way). But here the woman is not even replicating herself by cloning; instead, she is replicating (and destroying) her original IVF embryo.

(4) Helping save lives is generally a good thing, whether those saved are children or adults. Many couples who experience repeat miscarriages would be immensely grateful for medical help to stop this happening (which is sometimes available – e.g. NaProTechnology hormonal approaches can be helpful). In any case, we need to distinguish between health care allocation decisions – which may be open to criticism, but do not normally involve assaulting anyone – and using some, albeit very early human beings as a mere source of spare parts.

(5) There is more to an egg than nuclear – or indeed any – DNA. Remember, all the intended social mother will contribute with MST is the maternal spindle: a spindle is not an egg. I won’t get into the details of the research on donor conception (both quantitative and more qualitative) but will simply say that I don’t need to argue that MST or PNT would be worse psychologically than conventional surrogacy and/or egg donation (though in fact I think at least PNT definitely would be, given the two deliberate embryo destructions that would precede each conception, and leave their mark on the child). PNT, MST, conventional egg donation and surrogacy all involve the fragmentation or obviation of parenthood, and all can and (I think) should be avoided. In contrast, adoption can’t always be avoided, as some parents are simply incapable of bringing up their children properly: these children already exist and need to be cared for, even if adoption is not the ideal solution (as outcomes for adopted children seem to demonstrate). And regarding simply taking the risk of having a child naturally who might (but wouldn’t necessarily) have mitochondrial disease: this is potentially acceptable for those who believe they could be good parents to any affected child. In any case, it is certainly streets ahead of conceiving children simply for spare parts (as in PNT) or coopting another woman’s body to help one conceive/bear a child (as in MST or conventional egg donation or surrogacy).

Hi Simon (if I may),

In the first place thank you for highlighting our briefing, even if critically. You raise many points but I think it is worth focusing on one in some detail.

One key question is whether PNT involves the cloning of an embryo. If a clone must 100% genetically identical to the original then the answer is clear ‘no’, for the embryo generated by PNT will not share the mtDNA of the original. However, since the advent of cell nuclear replacement techniques in the 1960s, and their successful use in a mammal (Dolly the sheep) in the 1990s, the organism produced by SCNT has been termed a clone. This use of the term is very well established. The central case of cloning is from an adult cell to an adult clone, as with Dolly. Nevertheless, if the nucleus for CNT is taken from an embryo, and the resulting product of CNT is allowed to develop only to the early embryonic stage, it still makes sense to speak of the process as cloning: the cloning of an embryo. This indeed is what the Newcastle team claimed to have achieved in 2005.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/4563607.stm

If the generating of an embryo by CNT from a cell of an embryo is ’embryo cloning’, then PNT is also ’embryo cloning’, except with the peculiarity that, as it occurs at the one cell stage, the process necessitates the destruction of the original embryo and can generate only one clone. However the relationship of the generated embryo to the original embryo is the same as in CNT. At one point you seem to argue that the original embryo is not destroyed when its pronuclei are transfered, but surely the pronuclei themselves are not an embryo, just as a nucleus is not an embryo, neither in law nor in fact. One emrbyo ceases to be (in law and in fact) before a new embryo is created from the pronuclei and the enucleated donor embryo.

You may wish to defend this technique but you should not pretend that it does not involve cloning. PNT would have been illegal under the Human Reproductive Cloning Act 2001, and it is only being discussed now because the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 repealed the Human Reproductive Cloning Act 2001 and created a loophole which could permit reproductive cloning for people with mitochondrial disease, subject to the passing of future regulations. PNT is the thin end of the cloning wedge, the most minmal form of cloning, but it is a form of cloning and, if allowed, would be the first time a cloned human embryo could legally be implanted into a woman. This is something of which people should be aware.

Helen and David from the Anscombe Centre, thanks for your further comments. I will try to narrow the focus of the debate a bit. Helen, as I understand it, according to your ontology:

individual human zygote (single cell with pronuclei formed by sperm entering ovum) = individual human embryo = individual biological being = individual human organism = individual human child = individual human person

You wrote that “Natural twinning [production of identical/monozygotic twins] doesn’t mean that the embryo who twins was never an individual human organism – any more than cloning from an adult means that the adult was never an individual human organism”. So as I understand it, on your view of natural human identical twins, there was at the zygote stage just one human child, and then when the embryo divides, a second, natural clone human child is produced from the first. Now I assume that for natural identical twins you will say that both twins have two genetic parents, even though you think at least one of the twins is a natural clone, deriving its genes wholly from the earlier human child. So even if I grant your view (with which I strongly disagree) of PNT as cloning in which the resulting child derives the vast majority of its genes from an earlier natural child, why does PNT but not natural twinning result in a child with, as you earlier put it, “no genetic parents”?

In response to both of you, in claiming that PNT is not cloning, I haven’t suggested that cloning has to reproduce the original with 100% accuracy. My claims have only rested on the assertion that cloning is, conceptually speaking, reproduction, or copying of something, and not simply moving it or any of its parts. Dolly’s original was cloned because Dolly was copied, by means of transferring the nucleus of one of her somatic cells into an ovum. Generating an embryo by cell nuclear transfer (CNT) from the cell of a multi-celled embryo is producing a copy of it: the original embryo could (in principle, if not technically) persist, along with the new one. So I disagree with you David: a cloned embryo produced by CNT does not have the same relationship to its original as the zygote resulting from PNT has to anything else. The zygote resulting from PNT has no “twin”, living or dead. Nothing is copied in the PNT process. What is left behind when the pronuclei are taken from a zygote is not a zygote: it is a mere zygote part that cannot regenerate or maintain itself, and is incapable of growing into anything. It is like taking an adult human and leaving their skin behind, then replacing their skin with another. PNT is no more like cloning than organ transplantation is. Just as the use of a scalpel alone does not make a procedure an organ transplant, the transfer of nuclear material alone does not make a procedure a cloning. No zyogte is ever copied in PNT (rather, the most significant parts of one zygote are removed and combined with less significant parts of another zygote). No DNA is copied. No embryo is copied. No child is copied. No human person is copied. Since there is no copying, there is no cloning either.

David, you assert that “PNT would have been illegal under the Human Reproductive Cloning Act 2001”. That act outlawed placing “in a woman a human embryo which has been created otherwise than by fertilisation.” Your assertion that it would have outlawed PNT (which depends on your substantive view that two embryos, not one, are destroyed during PNT) is highly doubtful, and has never been substantiated in court. But in any case, that act would have made illegal various other (currently science-fictional) practices that are transparently not cloning, such as placing in a woman a unique, novel “designer” human embryo that was artificially built from scratch molecule-by-molecule. The 2001 act made no attempt to define PNT as cloning, either legally or otherwise.

In any case, as you note that outdated law was repealed and in the HFE Act 2008 there is an exception that is explicitly there to permit regulation allowing the implantation of eggs or embryos modified so as to “prevent the transmission of serious mitochondrial diseases”. To describe this careful and intentional exception in current law as a mere “loophole” is highly misleading.

Simon – thanks for your response. Yes, I think that natural twinning can involve the asymmetric ‘budding’ of an original embryo (alternatively if the original splits symmetrically, this might mean the original embryo was destroyed in the process of producing two new embryos – natural copies of the first).

We won’t normally know in the case of identical twins which twin, if either, is the genetic offspring of the social parents (of course, one of these parents will also be a biological/gestational mother, assuming she conceived and gave birth naturally, without using a ‘surrogate’ mother). ‘Accidents happen’, and we can’t argue from natural accidents like twinning to the desirability of deliberately manufacturing children who will have no true genetic parents but will be produced from two deliberately-destroyed embryos. That would be a bit like saying that because embryos naturally fuse together, we should fuse them deliberately – or that because heart attacks happen naturally, we should set off as many as we can. Plus with PNT the parentless embryo is produced in an entirely novel way with serious germ-line implications.

Note that with natural twinning there is no manufacturing process, deliberate quality control of embryos and discarding of ‘inferior’ embryos before they are transferred etc. Natural twins are thus in a far better position to be welcomed unconditionally by their parents than lab-conceived embryos, who are conceived – and all too often treated – more like objects of manufacture. Including, of course, those never intended to survive – like those IVF embryos used for PNT.

I must admit, I still don’t see why copying something requires the theoretical possibility of the first entity surviving: is that what you’d say about the deliberate splitting of early embryos (which was certainly called cloning at the time, though it wasn’t very successful)? If splitting e.g. a two-cell embryo was guaranteed to kill that embryo, would that suddenly make it not copying/cloning that embryo? I’m not sure I understand the ‘theoretical’ bit, as we can certainly imagine cases where some adult cloning method killed the adult every time (by splitting the adult into all his or her component cells).

The embryo/zygote resulting from PNT does have a ‘twin’ of sorts – just a dead one destroyed by the cloning process itself. Yes, I agree that what’s left behind when the pronuclei are harvested is not a zygote: that’s part of the objection, as it means the original zygote – plus the donor zygote used to form the bulk of the new, clone zygote – has been killed for its parts. But note that just as the discarded bulk of the couple’s embryo is not an embryo/zygote, neither are the isolated pronuclei: not until the new embryo is formed when the pronuclei are transferred will we again have a living embryo here (albeit created from the parts of now-dead ones). Taking the pronuclei is not like taking an adult, leaving behind the skin; it is more like taking a heart, leaving behind a dead body. The pronuclei are parts, as you rightly say: they are not a whole organism.

Helen, sorry it’s taken me a while to respond again. I’ll leave this one last contribution, then you’re welcome to have the last word.

I’m inclined to take your view that identical twins are a kind of natural tragedy as a reductio ad absurdum of your position. The thought that one of a pair of identical twins lacks proper, or as you say “true genetic”, parents – and that, unable to know which one of them is a result of this unfortunate accident, both identical twins either could or should have “personal identity issues” as a result is quite bizarre. But it is a view that you are logically committed to, in claiming that PNT children could or should have similar problems, and I respect your honesty in owning up to it.

I don’t see what’s wrong with “quality control” of very early embryos – if you mean trying to make sure that successful implantation and gestation occurs after IVF and that the child(ren) born is/are healthy. Of course, following Catholic orthodoxy, you believe that zygotes are sacred and are already individual human persons, so you will disagree about this. And of course that’s where your main objection to PNT lies, in addition to the orthodox Catholic objection to PNT, MST and IVF generally that they are not the “natural” processes of producing children. I just think there’s a more appealing alternative view, which is shared by the majority of the British public: that whether the procedure of producing a child is “natural” or “mechanical” doesn’t have any intrinsic moral relevance, and that very early human embryos are worthy of some moral respect and concern because of their relationship to us, but they are not human persons and do not deserve anything like as much respect or concern as the interests of any actual future child or any (potential) mother.

One of the dangers of confusing a zygote with a child, in my view, is that when you say a zygote “has been killed for its parts” when its pronuclei are transferred, this sounds like saying a child has been killed for its parts. But this is not the case. Rather, the same nuclear genetic information that would have been used to create an unhealthy child from one human cell has been used to create a healthy child instead, from (arguably) a different human cell. Merely killing a human cell for its parts is not at all morally questionable. We should surely be debating whether this is morally obligatory rather than whether it is morally permissible.

You make a good point about cloning not requiring theoretical survival of the original. I think I was mistaken, and should have said only that cloning something requires the theoretical possibility of creating more than one copy (either one copy in addition to the original that is left intact, or two new copies if the original is destroyed). That’s what distinguishes it from mere moving (something has to!). Splitting anything, including a two-cell embryo, it’s worth noting, is not *copying* it unless and until at least two separated parts grow back or are restored to resemble the original. PNT involves splitting, but could not involve copying in this sense, therefore it is not cloning.

Thanks again for your kind engagement in this thread!

Comments are closed.