Follow Brian on Twitter by clicking here.

Twitter, paywalls, and access to scholarship — are license agreements too restrictive?

I think I may have done something unethical today. But I’m not quite sure, dear reader, so I’m enlisting your energy to help me think things through. Here’s the short story:

Someone posted a link to an interesting-looking article by Caroline Williams at New Scientist — on the “myth” that we should live and eat like cavemen in order to match our lifestyle to that of our evolutionary ancestors, and thereby maximize health. Now, I assume that when you click on the link I just gave you (unless you’re a New Scientist subscriber), you get a short little blurb from the beginning of the article and then–of course–it dissolves into an ellipsis as soon as things start to get interesting:

Our bodies didn’t evolve for lying on a sofa watching TV and eating chips and ice cream. They evolved for running around hunting game and gathering fruit and vegetables. So, the myth goes, we’d all be a lot healthier if we lived and ate more like our ancestors. This “evolutionary discordance hypothesis” was first put forward in 1985 by medic S. Boyd Eaton and anthropologist Melvin Konner …

Holy crap! The “evolutionary discordance hypothesis” is a myth? I hope not, because I’ve been using some similar ideas in a lot of my arguments about neuroenhancement recently. So I thought I should really plunge forward and read the rest of the article. Unfortunately, I don’t have a subscription to New Scientist, and when I logged into my Oxford VPN-thingy, I discovered that Oxford doesn’t have access either. Weird. What was I to do?

Since I typically have at least one eye glued to my Twitter account, it occurred to me that I could send a quick tweet around to check if anyone had the PDF and would be willing to send it to me in an email. The majority of my “followers” are fellow academics, and I’ve seen this strategy play out before — usually when someone’s institutional log-in isn’t working, or when a key article is behind a pay-wall at one of those big “bundling” publishers that everyone seems to hold in such low regard. Another tack would be to dash off an email to a couple of colleagues of mine, and I could “CC” the five or six others who seem likeliest to be New Scientist subscribers. In any case, I went for the tweet.

Sure enough, an hour or so later, a chemist friend of mine sent me a message to “check my email” and there was the PDF of the “caveman” article, just waiting to be devoured. I read it. It turns out that the “evolutionary discordance hypothesis” is basically safe and sound, although it may need some tweaking and updates. Phew. On to other things.

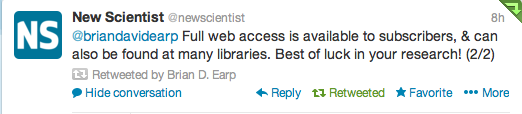

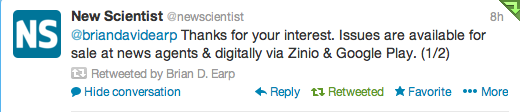

But then something interesting happened! Whoever it is that manages the New Scientist Twitter account suddenly shows up in my Twitter feed with a couple of carefully-worded replies to my earlier PDF-seeking hail-mary:

Uh-oh … that gave me pause. The implicit message seemed to be: “It’s all very well that you’d like to tweet your way around our pay-wall, but just to remind you, the article does cost something and if you would ever-so-kindly subscribe to us, we won’t tell anyone that you’re basically an unethical louse. Also, good luck with your research!” Yikes. So I turned to ResearchGate for advice.

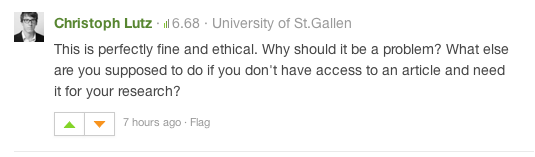

Is it OK to tweet one’s way around a scholarly pay-wall, I asked, or does that make one an unethical louse? Responses were quick and varied. Christopher Lutz said:

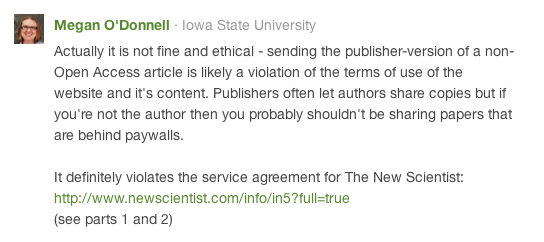

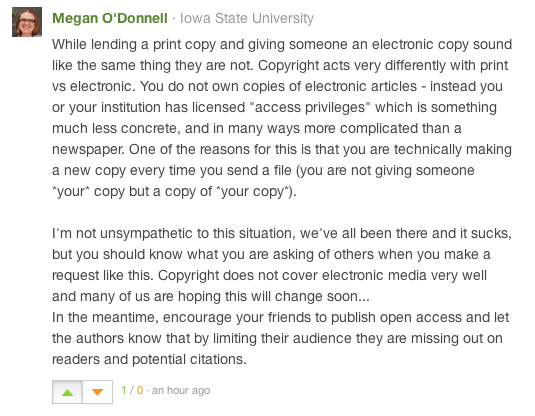

Whereas Megan O’Donnell thought otherwise:

Hmmm … Faced with such divergent opinion, I turned to one of the wisest and most ethical people I know for a conclusive take on the issue — my dear brother Sean. (Actually, I freaked out and posted my question on Facebook, and Sean just happened to reply.) Here is what Sean had to say:

Hmmm … Faced with such divergent opinion, I turned to one of the wisest and most ethical people I know for a conclusive take on the issue — my dear brother Sean. (Actually, I freaked out and posted my question on Facebook, and Sean just happened to reply.) Here is what Sean had to say:

With the exception of Mr. Valjean’s situation in Les Miserables (I endorse the taking of bread for starving children), “I don’t have the funds” has never been an acceptable reason for kids to take candy from a store [or] for teenagers to sneak in the back door of a movie, [etc.]. Looking at their “About Us” page (http://www.newscientist.com/people), New Scientist employs around 100 people with the proceeds from the paywall, which enables them to continue publishing great articles each month (something that many American newspapers are losing the ability to do as subscribers go away). NS offers a year’s subscription to their web archives for $21.25, offers a “Student” subscription, and makes their archives available to Students through Science Direct. If you want the fruit of other’s labors … you get to pay for it. That’s what rewards others for laboring. The answer to your original question is #clearlyunethical.

Shoot. I confess that I turned red. Had I really just stolen from New Scientist? Had I done as good as snatched a precious paycheck from the hands of some hard-working writerly staff-person? Chastened, I attempted a riposte:

Thanks for the thoughts, Sean. The background in my mind is that there’s a parallel debate going on about pay-walls for academic journals, and New Scientist sits on the border of that category: it’s available through Science Direct, is citable as academic scholarship, and I wanted to reference one of its articles for a paper I’m writing. I didn’t see an option to purchase an individual article, and I don’t intend to read a year’s worth of the magazine.

Now, let’s say that I had a subscription to the New York Times, because I really like the NYT, and I wanted to read it on a daily basis. And let’s say that a friend of mine — who lives next door, to keep it simple — does not read the NYT, but has heard that there’s an article in today’s issue on a topic that he happens to be researching for a school project. Would it be OK for me to take my copy of that particular article, that I paid for through my own subscription, walk over to my neighbor’s house, and lend him the article for a few hours?

What about just give it to him? What about make a photocopy and give him that? What about scan the article and send it to him by email? None of those actions strikes me as being clearly unethical, because someone would have paid for the yearlong subscription, and would be giving limited access, to one article, to someone who needed it for a specific purpose.

I copied my exchange with my brother over to ResearchGate. Megan O’Donnell was not exactly impressed:

Ok, fair enough. My next step was to head over to the New Scientist website and plunk down $21.25 for a yearlong subscription, just to cover my ethical bases; and I tweeted an apology to New Scientist, whose Twitter account manager graciously “favorited” my tweet. But I’m still not sure I know the right and wrong of all this. Is it absolutely morally impermissible for me to ask an academic colleague of mine to send a PDF of a pay-walled article? Under every circumstance? Any pay-walled article, ever? If my hypothetical colleague had the print version of the magazine, would it be OK if she “scanned” me a copy? Does it make a difference that I tweeted the request, rather than emailed it? What if I walked over somewhere and asked her in person? If I had fewer Twitter followers, would that make a difference? If too many people see a request at once, does that make it extra sleazy? Is this a sorites problem?

I look forward to learning your thoughts.

I find Megan’s response faulty in two respects.

One minor: from the fact that sharing copyrighted etc. stuff violates legal rules, it doesn’t follow that it is always morally impermissible. Sometimes it may be, sometimes not, and of course the value of upholding a basically decent system of legal rules must be considered, but it also depends on the circumstances. This would, I suggest, hold regardless of what minimally plausible ethical theory you apply. At the same time, anyone caught at thus breaking the law should, of course, be prosecuted and so forth according to due process.

One major: even if we were to agree with the legalistic premise that we shouldn’t ever break the law, this would in this instance not imply that Brian did anything wrong, since the statues cited do not imply that asking for an illegal act being performed by someone else or receiving a result of such an illegal act performed by someone else is unlawful. As indicated, copyright law is not like the criminal law around physical property.

Does this mean that Brian, morally speaking, is in the clear? Not necessarily, since illegal acts always create some (albeit in this case minor) risks for rule of law and public order and that we therefore as decent people should not in general resort to or incite illegal activities unless they are necessary for realising a sufficiently importnt good (or forestall a sufficiently important evil) . For instance, there might have been other ways to get the article in reasonable time than soliciting an unlawfully shared pdf. Might, for instance, a public library have had access, perhaps for a small fee? Or is Brian’s financial situation roomy enough to accommodate the fee for purchasing access from NS. If it isn’t, perhaps he should make it so by having a few pints less in the next few weeks, etc.

One thing, however, I am sure of: the marginal value of spending time figuring this out is not worth the goods thereby achieved.

That should be statutes, not statues, of course 🙂

Actually, Brian, I think you did us all (and in particular the NS) a favour. You found a loophole, used it and publicized it. The ball is now in the NS’s court, to either close it (I cannot imagine how) or offer an option to buy a single article (which should have been available in the first place).

It was very good of you to pay the NS subscription fee and apologise to them.

I think that the final comments you quote from Megan O’Donnell miss the point. It may be that the legal issues surrounding electronic and printed works differ, but it does not follow that the ethical issues are different. I don’t think your requesting a soft copy of the article was ethically significantly different from asking to borrow a book or a CD. It may, of course, be that asking to borrow a book or a CD is unethical, but lending stuff to friends and colleagues out of goodwill is so fundamental a part of human relationships that failing to reflect this would count as a weakness of any law that governs this area.

Having said that, there is a move towards open access in academic publishing (as you note), which is sometimes (and understandably) quite militant as a result of the arguably exploitative behaviour of some publishers, who get their material for free from academics but then want to sell it back to us at ridiculous prices (leading the Cambridge mathematician Tim Gowers to lead a boycott of Elsevier – there’s some information about it here if you haven’t come across it before: http://www.sparc.arl.org/news/look-inside-boycott-elsevier-qa-tim-gowers-and-tyler-neylon). According to your brother, NS does not fall within this category, since it pays a staff to produce its material. This should probably make us happier about paying NS than about paying certain other publishers. However, with publishers under pressure to embrace open access, and academics (and others) increasingly demanding it, it seems likely that publications like NS will soon need to find a way of funding its articles that doesn’t involve paywalls. Other publications manage this. I guess one option would be to cut costs by eliminating (or reducing) its printed copies. And offering an option to buy a single article would help, too, as Deborah comments above.

These are public, non-rivalrous goods — that ontology is the bottom line on evaluating the morality. (Following that eventually cuts through various notions of ‘lost income’, ‘violating agreements’, ‘stealing’, ‘getting benefit without paying’, ‘fruits of labour’, etc..)

If as many people as want to can use these goods — i.e. there is a beneficial abundance — how can there be a reason to restrict them? For things we decide fit such a class, and as far as it is possible to see a priori, their basic physical structure means there is no reason to physically restrict them. Furthermore, since we all gain from copies of them and at virtually no cost, sharing freely works as a general universalisable rule. Copying and sharing is basically moral in the cooperative sense of morality.

One might reply that there is not an abundance: effort and resources are needed to produce these goods. But production is separate from copying and their relation fails to support a priori restrictions. Does production necessarily depend on restrictions of copies? No, and in fact the opposite: production is enabled by copies of such similar goods in general being easily available.

And nor do rights-oriented counter-arguments work. If rights are for restricting interference, to protect individuals, then *non*-interfering activities cannot validly be restricted by rights. So since use of these ‘intangible’ goods as such fits ontologically that class of non-interering activities, copyright-like ‘rights’ cannot really be rights at all.

That leaves the only justification for copyright-like restrictions as the standard pragmatic economic one: that they might yield an overall public net benefit by supporting production. This is not something we can deduce from the features of the things, but it might be how things transpire in the actual world.

And there is the problem: that justification is entirely dependent on evidence, yet there is none sufficient (we do not know that the economy would not restructure itself in an equally or more efficient way). Since there is no default reason to restrict copying (on the contrary), and no evidence to suggest it is actually useful, why do it? Well, that is it, we should not be.

What remains is the general question of whether and when it is moral to disobey a rule that is itself immoral. That is likely well addressed elsewhere.

Consider the case where someone responds to your tweet by sending you a preprint of the paper, or a link to a preprint. In this case the journal has not done its work on the paper and it is just the author’s work. Clearly that is ethical (assuming it is not “draft: please do not circulate”).

Yet that preprint is rivalrous to the journal version: you are unlikely to download the journal version (and even less willing to pay for it) merely because it has been nicely formatted and a few typos corrected. So the journal might accurately count that as one paper less “sold” – from their perspective this is just as bad as a copy. But it cannot morally say this is a bad practice (beyond a semi-Kantian “what if everybody did this? journals would go out of business! And that would be bad!”), just something economically bad for them.

Conversely, being able to freely circulate papers in the research community is important. Authors do not care for journals, they want their ideas spread and cited.Researchers need each other’s research in order to work. The social good science and academia does is very much based on the free flow of information: restricting it reduces the overall good the community achieves. And that social good seems to be the moral reason to have journals, assuming they promote it.

Equating New Scientist to an academic journal is muddying the waters. The magazine is not written for academics, nor is it peer-reviewed. It is a layperson’s magazine, primarily intended for entertainment, although its subject is science. There are sound arguments for open-access journals, but they don’t apply to New Scientist any more than they apply to the Economist or the New Statesman.

You were not tweeting around a scholarly paywall. Track down the original papers that the magazine’s journalists used to inform their articles and tweet around THEIR paywalls and then we’ll talk. 🙂

Interesting discussion, but is it really about ethics? I think it is really about property rights. The question is not whether getting a free copy of an article behind a paywall is unethical, but whether it is theft – that is, against the law. I notice the reverse collapse (of the ethical into the legal) in arguments about non-therapeutic circumcision of children; too often discussions about whether it is ethical (i.e. in accordance with principles of bioethics, human rights etc) collapses into a discussion as to whether it should be illegal – a very different question. To go back to Jean Valjean, I think it is perfectly ethical for a starving person to steal food (so long as he does not injure somebody in the process), but he will still be arrested if caught – and rightly so, since the stability and propsperity of modern society depend on the inviolability of property rights. (As Anatole France remarked, the law in its majestic impartiality punishes rich and poor alike for stealing bread and sleeping under bridges.) So, as Beauchamp and Childress have pointed out, law and ethics can reach different conclusions.

Comments are closed.