Written by Melanie Trouessin

University of Lyon

Faced with issues related to gambling and games of chance, the Responsible Gambling program aims to promote moderate behaviour on the part of the player. It is about encouraging risk avoidance and offering self-limiting strategies, both temporal and financial, in order to counteract the player’s tendency to lose self-control. If this strategy rightly promotes individual autonomy, compared with other more paternalist measures, it also implies a particular position on the philosophical question of what is normal and what is pathological: a position of continuum. If we can subscribe in some measures of self-constraint in order to come back to a responsible namely moderate and controlled gambling, it implies there is not a huge gulf or qualitative difference between normal gaming and pathological gambling.

Faced with issues related to gambling and games of chance, the Responsible Gambling program aims to promote moderate behaviour on the part of the player. It is about encouraging risk avoidance and offering self-limiting strategies, both temporal and financial, in order to counteract the player’s tendency to lose self-control. If this strategy rightly promotes individual autonomy, compared with other more paternalist measures, it also implies a particular position on the philosophical question of what is normal and what is pathological: a position of continuum. If we can subscribe in some measures of self-constraint in order to come back to a responsible namely moderate and controlled gambling, it implies there is not a huge gulf or qualitative difference between normal gaming and pathological gambling.

If self-constraint measures already existed (for instance, self-exclusion from casinos), the innovative thing with Responsible Gambling is that it does not subscribe anymore in a prohibitionist strategy. This change is partly due to the change in public policy and the advent of “harm reduction” which aims to help drug users and behavioural addicts not to stop their addiction but to control it. This change is clearly linked when the traditional disease view of addiction began to be challenged: if you think that addiction is a chronic relapsing disease (as brain disease view thinks, but not only), you can only advocate abstinence for recovering addiction. For instance, in the AA literature, the former alcoholics are never cured but they only can be abstinent. A controlled drinking is not a possibility because they think the slogan “once an addict, always an addict” is true and that, with only one drink, you can relapse and be an addict again. There is thus a link between the radical disease view and the aim of abstinence. And on the other hand, between a less radical view of addiction, and the aim of harm reduction. With harm reduction, and programmes such as Responsible Gambling, the aim is not abstinence but reduction, and many thinkers claim it is a good think because it is more realistic and seem more attainable to addicts (Ladouceur, « Controlled gambling for pathological gamblers », http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15789190). This kind of new strategy is based on the idea that addiction can be understood as a loss of power or powerlessness not complete but partial. For Jim Orford, addiction is a question of “relative disempowerment” – “diminished but never completely lost” – and this kind of “pre-commitment” strategies can help to “reassert the power to manage forms of consumption that have become out of control”. It assumes people can organise “the environment so that temptation is reduced”. This definitely supports a view of addiction situated on a continuum with normal actions and weak-willed actions.

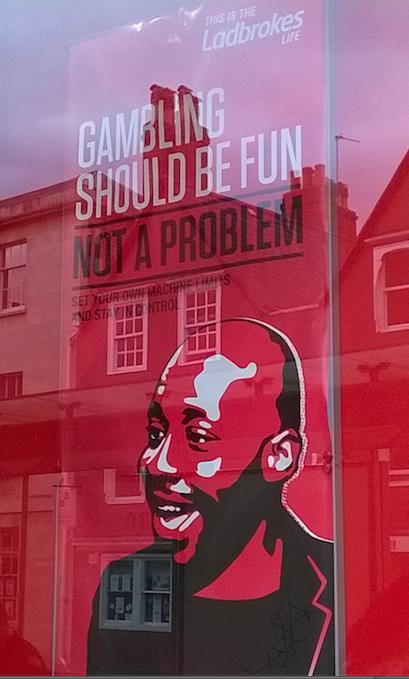

But, in the meantime, quite the contrary is expressed in the prevention part of the same programme. Everywhere on websites (or on casinos flyers), you can read this kind of message:

“For the majority of people, gambling is an enjoyable leisure and entertainment activity. But for some, gambling can have negative impacts”.

“A majority of people gambles in a responsible way, however for some people, gamble can become problematic”. (http://fr.info.winnings.com/responsible.aspx?vid=16919949&abtc=WIN13050)

If we try to analyse this kind of message, we can firstly notice that there is a clear distinction between normal gamblers and pathological ones. The former are the “majority of people” whereas the latter are only a minority of people. It seems to suggest that these people have a problem with gambling but which is independent from the gambling itself. It is a way to put emphasis on the pathological gamblers: they have a problem to control their behaviour, whereas most of people do not. This kind of message is given in order to reassure the majority of people, saying that they won’t become addicts. There is an opposition between, on one hand, majority, normality and on the other, minority and pathology. This opposition is redoubled by the opposition between pleasure, fun on one side, and the absence of fun on the other:

“Gambling should be fun”; “When the fun stops, stop”.

These slogans imply a particular definition of Gambling: the normal Game is a fun and limited one. This definition does not imply the possibility of pathological gambling and established a limit, a qualitative difference between normal and pathological Gambling.

On the whole, it seems that the Programme of Responsible Gambling want to have it both ways: saying there is a huge gap between normal gamblers and pathological ones for attracting a maximum of people while saying when you have became an addict, you can come back to a normal Gambling thanks to self-constraint measures. Because the two positions compared to the question of normal and pathological – discontinuity and continuum – are simultaneously involved in the Responsible Gaming, this strategy seems to imply something paradoxical.

This post is an abstract from a paper I gave in a symposium last year in Geneva, that will be published soon.

Bibliography:

Ladouceur, R., « Controlled gambling for pathological gamblers ». Journal of Gambling

Studies, 2005, 21 (1).

Elster Jon, « Gambling and Addiction », in Getting hooked : rationality and addiction.

Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Orford, J. Power, Powerlessness and Addiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Rosecrance, John, “Compulsive Gambling and the Medicalization of Deviance”. Social Problems, 1985, 32 (3) : 275–84