By Doug McConnell

Some argue that good medicine depends on physicians having a wide discretionary space in which they can act on their consciences (Sulmasy, 2017). Interestingly, those who are against conscientious objection in medicine make the exact opposite claim – giving physicians the freedom to act on their consciences will undermine good medicine. So who is right here?

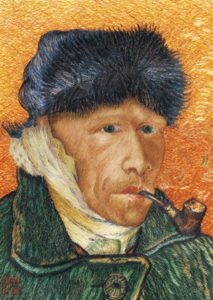

Professional discretionary space refers to the range of situations in which a professional is fre to act on her own judgment without deferring to patients’ wishes or authorities. There are several reasons to think that some discretionary space is needed for good medicine. If the physician had no discretionary space, then they would be like non-professional service providers who sell their services to any client who will pay for them. If we think that medical professionals should prioritise good medicine over client satisfaction, then they need the freedom to deny patient requests in order to pursue those goods. For example, they should be able to prevent medicine being detrimentally used for non-medical purposes, e.g. amputating an ear may be medically justified to remove a cancer but not to achieve an edgy ‘Van-Gogh-look’. Similarly, to respect the patient’s autonomy, the physician needs the discretionary space to judge when the patient has sufficient understanding of the clinical situation to make an informed choice. If physicians unquestioningly provide services requested by patients, they risk damaging the patient’s interests because the patient may be ignorant of the risks or overly optimistic about the prospects of treatment. Physicians can also better promote distributive justice if they have the discretionary space to refuse services that they judge will be futile or unnecessary, such as when a patient with a muscle tension headache requests a CT scan. Good medicine will tend not to be promoted if the physician must do what the patient requests because, unlike the physician, the patient is not professionally committed to good medicine and, typically, lacks the training to promote it anyway. Of course, one might also doubt physicians’ capacity to promote good medicine. We could set strict, comprehensive professional rules to prevent physicians from undermining good medicine. One problem here, though, is that we cannot anticipate the variety of clinical situations that will arise. In novel cases, there is a risk that strict rules will guide actions that the physician can see are at odds with good medicine. Therefore, to promote good medicine, one should not attempt to excessively regulate medical practice.

But what has all this got to do with conscientious objection in medicine? Sulmasy claims that anti-conscientious objection views require the physician to unreflectively do as the patient requests, thereby wrongly reducing professional medicine to a service-providing occupation (2017, 22-26). On his view, this severe restriction of discretionary space leaves professionals unable to protect and further good medicine.

However, Sulmasy has been attacking a strawman because one can rule out conscientious objections without eliminating the physician’s discretionary space. Anti-conscientious objection views usually require the physician to act in accordance with the law, professional policies, and the principles of good medicine. This entails that, ‘if a service a doctor is requested to perform is a medical practice, is legal, consistent with distributive justice, requested by the patient or their approved surrogate, and is plausibly in their interests, the doctor must ensure the patient has access to it’ (Savulescu & Schuklenk, 2016, 167, note 1). These restrictions hardly eliminate discretionary space. The professional is left to judge which laws, professional policies, and principles of good medicine apply in any given situation and how to resolve conflicts between them. This means that the physician can refuse to provide CT scans for headaches or Van Gogh style cosmetic surgeries. One is free to act on one’s conscience to the extent that it aligns with the law, professional policies, and professional ideals.

But even if anti-conscientious objection views don’t eliminate discretionary space, they do narrow it, so Sulmasy might claim that it is this narrowing that results in worse healthcare relative to a wider discretionary space. To assess whether a wider discretionary space might result in better medicine, we can assess Sulmasy’s own account.

Sulmasy believes that the only constraints we should place on physicians’ discretionary space derive from the need for religious and moral tolerance. On his view, physicians can publicly act in accordance with their personal religious and moral beliefs as long as their actions are not destructive to society. Sulmasy specifies three conditions (but I will only deal with two here) for assessing whether a conscientious public practice is destructive of society and, therefore, whether it should be tolerated. First, if the practice undermines or contradicts the principle of tolerance itself, then it cannot be tolerated. This condition rules out discriminatory conscientious actions because it is inconsistent to ask others to tolerate one’s intolerance toward, say, people of a particular race, gender, or sexual orientation. Second, if conscientiously refusing a service entails a substantial risk of serious illness, injury, or death to others, the conscientious refusal cannot be tolerated because it would be destructive of society. Conscientious refusals of service that merely cause others inconvenience, psychological distress, or mild symptoms are not destructive of society and so should be tolerated.

Unfortunately, Sulmasy’s wider discretionary space does not promote good medicine as he claims, in fact, it leaves several features of good medicine completely unprotected. The core of the problem is that Sulmasy would tolerate all medical practices that are not destructive to society, however, some practices that are not destructive to society are, nevertheless, contrary to features of good medicine.

First, Sulmasy places little, if any, limit on what counts as a medical indication. If a physician judges that van Gogh cosmetic enhancements count as medical indications, there is nothing to stop him providing such procedures if patients requests them. If some physicians believe that whatever the patient wants counts as a medical indication, then it seems that the only indications ruled out as non-medical will be those it would cause destruction to society to treat. Therefore, Sulmasy’s tolerance conditions cannot prevent medicine being reduced to mere service provision where individual physicians are happy to be service providers (the very thing he incorrectly accused anti-conscientious objection views of doing). Sulmasy’s conditions would also tolerate physicians who denied that commonly accepted ailments, such as, rashes, headaches, mild depression and anxiety, were medical indications because, if untreated, those conditions won’t cause the patient substantial risk of serious illness, injury, or death. By tolerating conceptions of medicine that deviate from objectively good medicine, we expose patients to harm they would not be exposed to if all physicians were obliged to act in accordance with good medicine.

Second, Sulmasy’s tolerance conditions don’t require physicians to enter fiduciary relationships with patients. The tolerance conditions assume that we give each other’s interests equal weight and say nothing about how to proceed in fiduciary relationships where one party gives extra weight to the other party’s interests. Giving each party’s interests equal weight makes sense outside fiduciary relationships but within fiduciary relationships, the party with the fiduciary duty should place greater weight on the others’ interests and, so be prepared to go against his conscience in a subset of cases where he needn’t in non-fiduciary relationships. The lack of fiduciary duty is unsurprising given that, when deciding whether to conscientiously refuse a service, the physician only needs to consider society’s interests. The only reason that the physician must void causing serious illness, injury, or death to the patient is because it would be destructive to society. The patient’s interests are beside the point.

Third, Sulmasy’s conditions don’t require physicians to be sensitive to patients who lack autonomy. According to his conditions, physicians can provide patients any treatment they ask for as long as those treatments don’t risk serious illness, injury, or death. Less than fully autonomous and outright incompetent patients might ask for a variety of things that are not in their best interests yet that would not risk serious injury, illness or death. For example, hypochondriacs might request treatments for imaginary diseases that would expose them to side effects. On Sulmasy’s view, the physician only has to make sure those side effects don’t risk serious injury, illness or death; he is under no further obligation to work out what is in the patient’s best interests or if the patient is a competent judge of his own best interests. In summary, Sulmasy’s argument that we should adopt his wide discretionary space because it supports good medicine is flawed.

A more obvious path for ensuring good medicine is to derive rules governing physicians’ discretionary space from our conception of good medicine. If, for example, respect for patient autonomy, fiduciary duty, promotion of the patient’s objective health, and just distribution of finite medical resources are part of good medicine, then we should adopt professional rules that ensure physicians pursue those goods or, at least, don’t act contrary to them. If Van Gogh-style cosmetic surgeries are inconsistent with good medicine then we can prohibit such practices.

Obviously, we will disagree over what counts as good medicine and epistemic humility should lead us to accept that a range of conceptions of good medicine are reasonable.. The public healthcare system should adopt a conception of good medicine that is sufficiently broad to be acceptable to the public given their range of reasonable individual conceptions of good medicine. We can then develop a set of professional rules that promote that broad conception of good medicine. In short, if we are interested in ensuring good medical practice then we should prohibit conscientious refusals of service where they are at odds with professionally agreed, appropriately bounded, standards of good medicine. Providing a wider discretionary space than this only gives practitioners the option to engage in sub-optimal medical practice.

The views presented here are elaborated in my 2019 paper in Bioethics, “Conscientious objection in healthcare: How much discretionary space best supports good medicine?”

References

McConnell, D. (2019). Conscientious objection in healthcare: How much discretionary space best supports good medicine? Bioethics, 33, 154-161.

Savulescu, J. Schuklenk, U. (2016). Doctors Have no Right to Refuse Medical Assistance in Dying, Abortion or Contraception. Bioethics; 31: 162–70.

Sulmasy, D. P. (2017). Tolerance, Professional Judgment, and the Discretionary Space of the Physician. Cambridge Q Healthc Ethics; 26: 18–31.