Vaccine Passports as a Human Right

The main way to control the pandemic, as we have all painfully found out, has been to restrict the movement of people. This stops people getting infected and infecting others. It is the justified basis for quarantine of people who have been in high risk areas, lockdown, isolation and vaccine passports.

It is the foundational ethical principle of any liberal society like Australia that the State should only restrict liberty if people represent a threat of harm to others, as John Stuart Mill famously articulated. This harm can take two forms. Firstly, it can be direct harm to other people.

Imagine you are about to board a plane (remember that…) Authorities have reason to believe you are carrying a loaded gun. They are entitled to detain you. But they are obliged to investigate whether you have a gun. And if you are not carrying a gun, they are obliged to free you and allow you to board your plane. To continue to detain you without just cause would be false imprisonment.

Having COVID is like carrying a loaded gun that can accidentally go off at any time. But if vaccines remove the bullets from the gun, they are not a risk to other people and should be free.

Vaccine passports are thus a human rights issue under conditions of lockdown like Melbourne and Sydney are experiencing (the situation is different in Europe where lockdowns have been relaxed), if vaccines reduce transmission to other people sufficiently. Vaccination removes the authority and justification to restrict people’s liberty.

It is not discrimination to continue to restrict the liberty of the unvaccinated – it is just like quarantining those who have entered from high risk countries overseas. Their liberty is restricted because they are a threat to others. Discrimination occurs when people are treated differently on morally irrelevant grounds – differential treatment on the basis of differential threat is morally relevant. For example, to enter some countries, travellers must be vaccinated against Yellow Fever and receive a card as a vaccine passport. No card, no travel.

Are COVID Vaccine Passports a Human Right?

Do COVID vaccines fit into this justification for vaccine passports?

Hard to say. They appeared to reduce transmission of the original alpha variant by 50-60% (even on just one dose) but it is unclear the extent to which they reduce transmission of delta. To let the vaccinated roam free and restrict the freedom of movement of the unvaccinated would be discrimination if the vaccine does not significantly reduce transmission.

One analogy is that requiring vaccination is like requiring a surgeon to scrub before an operation. Or an analogy I have used is that vaccination is like wearing a seatbelt – it is good for the wearer and for others in the car, as well as the health system.

But these analogies are flawed in two ways for COVID. Firstly, vaccination likely does not reduce the chance of infecting others to the extent of surgical scrub techniques. And secondly, washing your hands or wearing a seat belt benefit all concerned; vaccines have (very rare) side effects, including lethal ones. It’s true that seat belts can kill you but overall they are expected to prevent more harm than they cause for everyone who uses one– but vaccination for COVID in lower risk groups such as children and young people is less clearly in their interests, though it is very clearly in the interests of older people.

The inherent, unrecognised and unresolved problem in the vaccination and vaccine passport debate is one of proportionality. Vaccines may reduce transmission but do they reduce it enough to warrant mandates, including restricting freedoms of the unvaccinated? If vaccines were risk-free (like washing your hands), the mandating them would be reasonable – but the current vaccines do have extremely rare risks which nevertheless may be a factor to weigh for groups at lower risk from COVID, such as children and young people.

Burden on Health System

There is, however, a second way in which we can harm other people besides directly infecting them. We can use up a scarce resource like ICU beds by getting ill. In a public health system, we can indirectly harm others by taking more than our fair share of resources. Though Mill explicitly rejected “harm to self” as a justification for coercion, that was before a public health system with finite resources.

If vaccines significantly reduce the chance of getting seriously ill in a pandemic, then there can be a justification for using coercion to employ them to protect the health system in a public health emergency.

Again, proportionality is key: the strain on the health system must be severe. Otherwise any measure to promote health could be mandated, like giving up smoking, drinking, eating unhealthy food, exercising, etc. Freedom has some value and that includes the freedom to take on some risk.

How much risk we should tolerate and what level of coercion is justified depends on the safety and efficacy of the vaccines, the reduction in transmission, the gravity of the public health problem, the effectiveness of less liberty restricting measures, the costs of coercion and ultimately, the value of health and liberty.

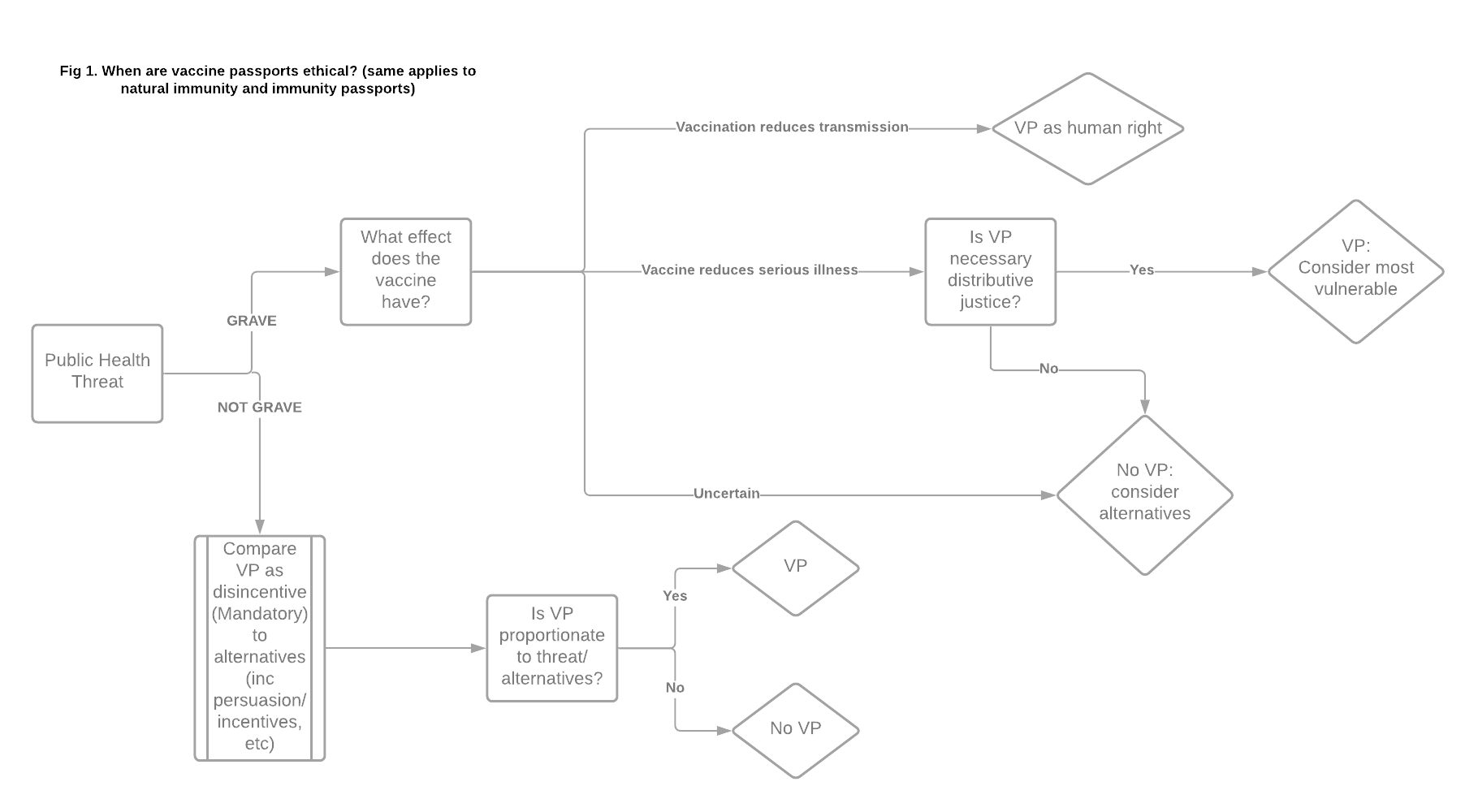

Figure 1 provides a way to consider these factors should be considered but there is reasonable disagreement how these should be defined and weighed.

Do COVID vaccines satisfy this criterion of reducing serious illness in a public health emergency? The evidence is strong that they prevent serious illness with delta.

But how grave is the public health emergency? Would Australia run out of ICU beds without vaccine passports or other coercive measures? That is difficult to say – to introduce vaccine passports ethically requires either showing vaccines reduce transmission significantly or that without them, we would face an health system crisis that is not reasonably sustainable.

Restricting people’s liberty, for example by vaccine passports, can be ethically justified in certain circumstances – but we need good evidence to justify them. Under conditions of lockdown, they can be a human rights issue.

Everything I have said about vaccine passports applies to natural immunity, which appears to offer even better prevention of transmission and serious illness than vaccination alone. (Of course getting infected without vaccination carries significant risks, so vaccination is by far the best strategy)

Discrimination and Selective Restriction of Liberty

Most people believe that restrictions of liberty, like vaccine passports, have to be universally applied or they are discriminatory. That’s wrong. Selective restriction of liberty can be justified for certain groups. This is what happens when we quarantine travellers because they are at increased risk of infecting others.

Selective restriction of liberty, including selective mandatory vaccination or passports, could be justified for “super spreaders” (those more likely to infect others, eg those attending large events) or those more likely to become ill (particularly the elderly but other also high risk groups). On the latter approach, vaccine passports are more appropriate for older rather than younger people as they are the ones most likely to benefit.

Consent

The problem in public health is that the person who makes the sacrifice is often not the one who benefits. By mandating a measure, the government is deciding to impose a burden on one group sometimes to benefit a different group. The person who suffers the vaccine-related side effect (although very rare) may not have suffered adversely from COVID.

For this reason, consent is important. Because whatever we do involves risks, getting vaccinated or risking getting COVID, it is preferable to consent to the particular risks for yourself, rather than have others impose them.

Responsibility?

If people are choosing which risks they take, it is tempting to hold people accountable for the consequences of their free choices. That would imply giving those who become ill after refusing vaccination lower priority if health resources are limited.

This requires that we can attribute responsibility to the individual, rather than their peer group, education, culture or other social factors. It requires that responsibility is treated equally across health care: we should not single out COVID risky behaviour without treating other dangerous lifestyles, such as risky sex and unhealthy habits, in the same way. And it will limit the kinds of lives people can freely lead by making risky alternatives more difficult to pursue. Ultimately it depends on what price we place on freedom and health.

Road fatalities would be reduced by drastically reducing speed limits. Yet we balance lives lost on the roads (and carbon emissions) with transport efficiency, pleasure and liberty. The same will eventually happen as we learn to live with COVID.

Conclusion

Vaccine passports could be justified in Australia. But whether the burden of proof rests with the Government to show the vaccines significantly reduce transmission (which they don’t appear to) or that the health system could not reasonably cope without them, or the burden rests on those who oppose vaccine passports depends on whether we value liberty more than health. Different countries will reasonably differ on this trade off.

Vaccine passports could be also justified for certain groups of superspreaders or those more likely to become ill. This creates inequality but we face a trade-off between equality vs maximising public health and liberty.

Ethics is about weighing different values. Decisions about vaccination should be fundamentally ethical, not political, or purely medical.

Comparison Covid to the loaded gun is false.

Everybody has a knife in the kitchen to cut the bread or meat. With one movement the knife can be also used to injure or even kill somebody and you do not have to be quite skilled to do this. Also a car can be used as weapon.

We have to consider the risks of our behaviour. If a patient in hospital accepted the line of argumentation mentioned above he or she could not go through any operation. Because it would be risky.

So the main principle must be proportionateness not making comparisons that are not fitting.

The loaded gun analogy is good because I stipulated: “a loaded gun that can accidentally go off at any time.” You don’t have any control over whether you infect someone else with COVID (except physical distance) or holding a gun that can accidentally go off (except by giving it up). You do have control over whether you stab someone with a knife or drive a car into a crowd – you can simply choose not to do it.

Of course we have to consider the risks of our behaviour – and the benefits. When the expected utility is positive (like having surgery to attempt to remove a cancer), we should do it. When the expected utility is negative (and the risks outweigh the benefits), we shouldn’t.

This is extremely dangerous territory. There are so many false assumptions it’s hard to know where to start. Perhaps the best starting point would be to consider ‘stages of genocide’ on the Genocide Watch website. We’re about halfway through the preparatory stages for genocide of the unvaccinated.

But the question is if COVID is so serious danger that it allows to introduce the Plato’s uthopia in which the non-elected philosophers rule according to some ethical principles that are arbirtrary determined by them in the charts, numbers, codes, patterns. The other people are just guardians or workers, nothning more.

In the open society the law rules and such society is not governed by some aim or ideology. The correct solution is the one that is chosen in regularly and free elections in which people choose the government for some limited period. That is why that the question of COVID can be neither purely ethical

nor purely medical. If the COVID and the government’s measures regarding COVID impacts the peoples’ lifes widely, it must be always POLITICAL question in which the democratic politicians decide. The ideal expert or ethical solution do not exist.

Comments are closed.