by Tolulope Osayomi and Mofeyisara Omobowale / first published 25th November on Torch News

The roundtable discussion “From Covid-19 to MPox: Lessons from The Humanities? “, organized by Medical Humanities Hub at TORCH and the Uehiro Oxford Institute, featured four panelists with diverse disciplinary approaches to public health crises. Two of the panelists were Oxford-based scholars in History (Utsa Bose) and Philosophy (Alberto Giubilini). The two authors of this blogpost are based at University of Ibadan in Nigeria and reflected from the perspective of Medical Geography (Tolulope Osayomi, currently AfOx Fellow) and Medical Anthropology (Mofeyisara Omobowale).

The roundtable discussion was based on a blogpost for the Medical Humanities Hub at TORCH that can be found here.

Tolulope Osayomi:

My presentation,“Ubuntizing the Global Response to Mpox: A Call for Solidarity in a Health Crisis” focused on the importance of an approach rooted in the philosophy of Ubuntu, which reminds us that “I am because we are.”

I argued that the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the interconnectedness and interdependence of human societies. It revealed shared vulnerabilities and the urgent need for global solidarity in responding to health crises. There was however some discussion with the other panellists on the issue whether these types of public health crises might instead reveal differences in vulnerabilities that make applications of principles like solidarity more challenging.

From my point of view, as Mpox resurfaces, it underscores the necessity of applying what I take to be the lessons learned:

- Disease Diffusion: Global connectivity drives public health risks, with air travel enabling the spread of diseases like SARS, Ebola, and Mpox.

- Geographies of MPox: Mpox’s neglect in Africa since the 1970s calls for a moral and empathetic global response.

- The Way Forward: An Ubuntized response requires solidarity, moral responsibility, and empathy, recognizing that “No one is safe until everyone is safe.”

Again, this last claimed was challenged by some panelists, but this discussion reveals precisely the importance of a humanized global response that can allow us to understand our differences, as well as our commonalities. Such an approach must address health crises with pluralistic histories and diverse geographies at its core. By fostering collective action and compassion, we can create more inclusive and resilient health systems.

I am grateful for the insightful discussions today in the Colin Matthew Room, Radcliffe Humanities, Oxford. Special thanks to the Chair, Erica Charters; the co-panelists: Alberto Giubilini, Mofeyisara oluwatoyin Omobowale, and Utsa Bose for their contributions to this timely and great conversation. I am also grrateful to the Africa Oxford Initiative for my AfOx Fellowship.

Let us continue to reimagine global health responses for a better, more equitable future.

Mofeyisara Omobowale:

I approached the discussion from an Auto-Ethnographic perspective. I argued that infectious diseases and pandemics have always had devastating impact on human history and biology. Infectious disease has likewise always played a major role in the evolution of human species and has been a prime mover of societal transformation. Human groups are major facilitators in the spread of infectious diseases through culturally coded patterns of bahviour and changes in patterns of relationships with both the environment and infectious disease agents.

COVID-19 is yet another pandemic whose spread was facilitated by human culturally coded patterns of behaviours. The pandemic further reiterates that, while caring for mankind requires the important contribution of medical professionals, prevention and management of disease and mortality are a social process requiring medical humanities to play a critical role. In my view and experience of the social reality of the pandemic, the emergence, progression, threat, and management of COVID-19 offers a strong demonstration of how different nuances mix, emphasizing the significance of understanding local contexts in pandemic preparedness and management. I highlighted the lessons from some of the challenges we faced, such as lack of understanding of social constructions of health, healing and prevention; re-emergence of misinformation, disinformation and conspiracy theories; class-based mistrust; and the critical roles played by medical humanities professionals in addressing such challenges.

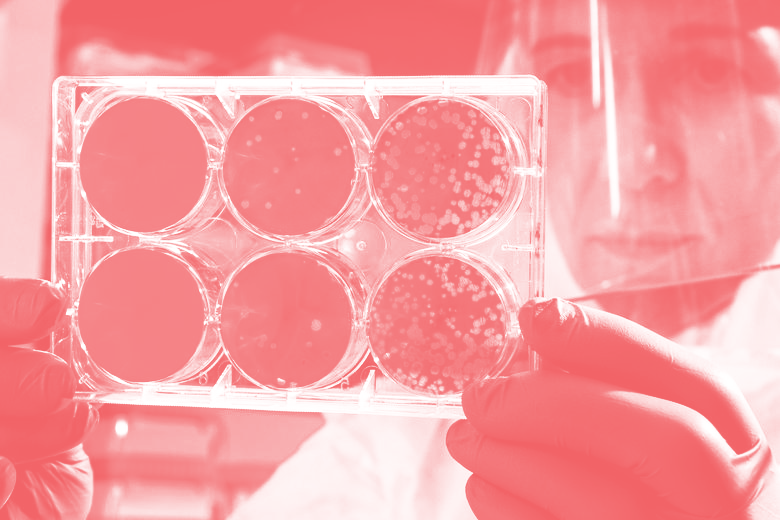

I concluded that one of the important lessons is that COVID-19 signals the importance of multidisciplinary approaches in the battle against pandemics. Outbreaks of Mpox and strategies to manage them cannot be viewed solely from the microscope of medical professionals. The Humanities microscopes must be acknowledged as playing a cruicial role . Understanding of local context is key to successful prevention and management of pandemic.

I wish to express my gratitude to everyone who participated in the discussion in person and online and the organizers for the invitation to participate in the roundtable.

German sociologist Ulrich Beck in connection with the modernity talks about “the risk society”.

Anthony Giddens writes about “second modernity”. While Zygmunt Bauman about his “liquid modernity”.

That all means that our society wipes off the traditional differences e. g. differences between rich and poor ones or differences between healthy or sick ones.

The reaction of the modern West societes on covid 19 is evidence of this.

The massive and blanket pandemic measures made no difference between groups that were threatened by the disease and those who were in no risk. All were isolated, all were forced to wear the face masks.

According to Beck for the risk society is also typical its REFLEXIVITY.

That means the society due to its basic characteristics and achievements (i.e. electronic communication, massive international transport) produces some risks and on these unintentional risks the society reacts reflexively.

Such reaction is no deliberate nor thoughtful. It is just spontanneous (like we close eye when we see some object heading to it). This only produces the other risks and externalities.

Such society reminds somebody who by chance walked into the swamp and the more movements he makes to get out o fit the more he drowns.

All we could watch during covid 19.

The electronic media instantly spread the panic.

The politicians were caught in tow of this panic. The experts simply did not know what to do because they were ask to solve the question how to control society. But such question cannot be anwered scietifically.

So in panic we adopted pointless measures and we only produced non-intended and tragical consequences. The fear of politicians from the legal responsibility (see the concept of blame culture) was the primary reason why the measures were approved.

We accepted that the will of mankind is not limited. We accepted that the death or illness are not natural part of our life but they are the elements that can be in all circumstances prevented and it is our responsibility if we fail to prevent it.

These are very dangerous and totalitarian ways of thinking.

Comments are closed.