First synthetic embryos: the scientific breakthrough raises serious ethical questions

Weizmann Institute of Sciences

Julian Savulescu, University of Oxford; Christopher Gyngell, The University of Melbourne, and Tsutomu Sawai, Hiroshima University

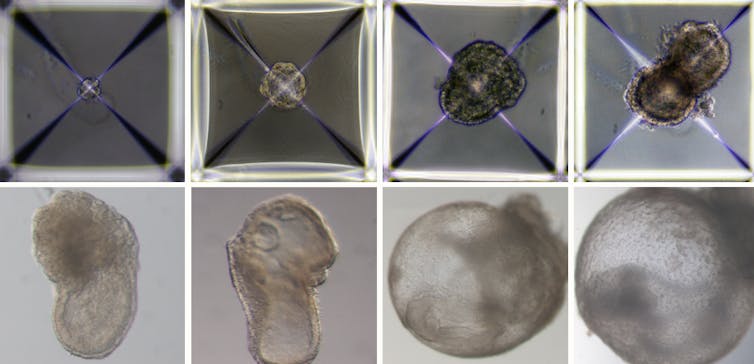

Children, even some who are too young for school, know you can’t make a baby without sperm and an egg. But a team of researchers in Israel have called into question the basics of what we teach children about the birds and the bees, and created a mouse embryo using just stem cells.

It lived for eight days, about half a mouse’s gestation period, inside a bioreactor in the lab.

In 2021 the research team used the same artificial womb to grow natural mouse embryos (fertilised from sperm and eggs), which lived for 11 days. The lab-created womb, or external uterus, was a breakthrough in itself as embryos could not survive in petri dishes.

If you’re picturing a kind of silicone womb, think again. The external uterus is a rotating device filled with glass bottles of nutrients. This movement simulates how blood and nutrients flow to the placenta. The device also replicates the atmospheric pressure of a mouse uterus.

Some of the cells were treated with chemicals, which switched on genetic programmes to develop into placenta or yolk sac. Others developed into organs and other tissues without intervention. While most of the stem cells failed, about 0.5% were very similar to a natural eight-day-old embryo with a beating heart, basic nervous system and a yolk-sac.

These new technologies raise several ethical and legal concerns.

Read More »First synthetic embryos: the scientific breakthrough raises serious ethical questions