Mummification and Moral Blindness

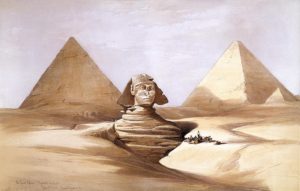

Image: The Great Sphinx and Pyramids of Gizeh (Giza), 17 July 1839, by David Roberts: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Words are powerful. When a word is outlawed, the prohibition tends to chill or shut down debate in a wide area surrounding that word. That tendency is much discussed, but it’s not my concern here. It’s one thing declaring a no-go area: it’s another when the mere use or non-use of a word is so potent that it makes it impossible to see something that’s utterly obvious.

There has recently been an excellent and troubling example. Some museums have started to change their labels. They consider that the use of the word ‘mummy’ demeans the dead, and are using instead the adjective ‘mummified’: thus, for instance ‘mummified person’ or ‘mummified remains’. Fair enough. I approve. Too little consideration is given to the enormous constituency of the dead. But using an adjective instead of a noun doesn’t do much moral work.

Consider this: The Great North Museum: Hancock, has on display a mummified Egyptian woman, known as Irtyru. Visitor research showed that many visitors did not recognise her as a real person. The museum was rightly troubled by that. It sought to display her ‘more sensitively’. It’s not clear from the report what that means, but it seems to include a change in the labelling. She will no longer be a ‘mummy’, but will be ‘mummified’. She is a ‘mummified person‘: She’ll still remain in a case, gawped at by mawkish visitors.Read More »Mummification and Moral Blindness