Written By William Isdale and Prof. Julian Savulescu

This article was originally published by The Conversation

Last year, an estimated 12 to 15 registered organ donors and candidates for donation had their decision thwarted by relatives. This was due to the so-called family veto, which enables family members to prevent organ donation even if the deceased person had registered to be an organ donor.

Currently, if an individual decides they don’t want to be a donor, they can register an objection that has legal protection. But the decision to be a potential donor, as registered on the Australian Organ Donation Register, has no such protection.

The family veto can prevent a donation request from proceeding for almost any reason, no matter how emotionally clouded, or even where it is based on religious or philosophical beliefs the deceased would not have agreed with.

In the words of the National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines:

If the objection is unlikely to be resolved or the prospect of organ and tissue donation is causing significant distress to close family members, the process of donation should be abandoned, despite the previous consent of the deceased.

Legally, the Human Tissue Acts in the various states and territories empower doctors to proceed with donation where there is written consent (as on the Australian Organ Donation Register form).

This means doctors can proceed with organ donation despite the family’s wishes, however most wouldn’t go against the family veto for fear of public backlash. So should we scrap the family veto?

Arguments against the family veto

One argument for removing the family veto is that individuals have a right to decide what happens to their body after they lose mental capacity or die. Generally, the law recognises such rights.

For instance, an individual’s decisions about how to distribute their property after their death – as expressed in a will – are legally protected (with limited exceptions). Similarly, an individual can decide what will happen to their bodies after they lose mental capacity through an Advance Care Directive. Individuals can also leave those decisions to others they trust, including family members.

If individuals have a moral entitlement to leave their estate to benefit others of their choosing, why should they not also have the right to leave their bodies to save the lives of others, where it can be used?

A second argument against the family veto concerns its consequences. Namely, a decision to prevent a donation from proceeding, by using the veto, significantly affects a larger group of people – those who will die or continue to suffer in the absence of transplantable organs. Their interests must be weighed in considering the moral legitimacy of the family veto.

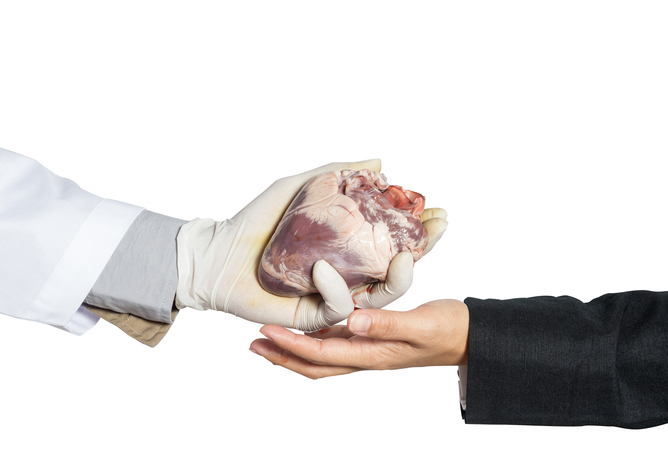

There’s an argument for the greater good. from www.shutterstock.com

There’s an argument for the greater good. from www.shutterstock.com

Reasons for retaining the veto

It is often said that retaining the veto is necessary to avoid causing additional distress to family members at a difficult time.

However, following an individual’s Advance Care Directive may lead to their death. Or a person’s will might distribute all of their property to the local animal shelter, instead of their relatives. This may cause distress to family members, but that distress does not trump their right to decide.

Second, there is no reason why distress caused to a candidate-donor’s family should always be privileged over the distress felt by those who need an organ, or their families. The interest of candidate organ-recipients in not dying is far more morally significant than the interests that family members have in avoiding additional distress.

Further, it is possible that the need to make the difficult decision actually contributes to family distress, and it may be less stressful if donation proceeded in accordance with a deceased person’s expressed wishes.

It may also be argued that, in practice, only a very small number of organs end up being wasted as a result of the family veto. As mentioned earlier, roughly 12 to 15 individuals last year had their donation wishes vetoed.

However, because each donor can provide organs or tissue that benefit up to ten other people, potentially 150 people annually are denied life-saving or life-enhancing transplantation as a result of the veto. In any case, practices that result in more deaths than necessary are repugnant in the absence of some compelling moral reason.

A final argument for retaining the veto is that without it, the supply of organs would fall. Usually this is explained on the basis that people may become fearful and public trust in the donation system would be undermined if the family veto were removed. If this is true, the veto should be retained.

However, it is speculative. There is no evidence available to settle the dispute, because no country has removed the veto in circumstances where the patient had signed up to be an organ donor. It may be equally plausible that removing the veto could increase donation rates, since offering legal protection for donation decisions may encourage more people to sign up.

The family veto is morally repugnant unless removing it would result in a decrease in the supply of transplantable organs. The absence of empirical evidence currently makes it impossible to settle this dispute.

Australia should trial the removal of the family veto in one or more state or territory. If properly monitored, it should be possible to discern whether removing the veto has a negative impact on donation levels. The results of such a trial could then inform decisions about whether the veto should be removed nationwide.

The article was interesting but in my opinion if you register to donate your organs or tissue that is your wish to do so. I don’t feel it is ethical of family members to veto a decision already made by the donor when he/she had sound judgement. The donor’s wish should be carried out, and not changed because family members are stressed out over the situation. However, when it comes to minor children I think it is the responsibility of the parents or guardians to make the decision whether or not they want to donate their child’s organs or tissue. When the child understands the meaning of being a donor and wishes to donate his/her organs; then I feel child’s wishes should be followed through by the parents or guardians.

I feel that the family of the deceased or loss of mental capabilities should respect the decision of that person. It was that person’s right to make that choice with their body. Having a child that passes, I can see where the family can come in have an opinion on what can be done, but the other family members should respect the decision that the mother and father makes for their child. In todays world everything has changed so much, lot of people think that things should be done their way no matter what relationship is to the person. Having different types of religions out there today could play a part in family decision, since the family can mixed religions in the same family. Families should respect other families decisions and support each other in the tough times of dealing with the pain of a love one.

As one who is listed as an organ donor and has been for many years I have had the argument with my mother related to my clear and stated wishes. My mother promises that she will fight any organ donation efforts I have made. I do not feel it is ethical for anyone to step in and revers an organ donors wishes. I also have a family member who has benefited from organ donation. While she has been able to rely on live family donors this possibility has ended. She will need to use cadaver donors in the future. My mother supports this because the donor is not me. While I cannot begin to reason with her, my wishes are clearly stated.

If something happens to me there will be far more people fighting for my true wishes than the one fighting against them. In the end donation is a personal choice that I feel unethical to challenge.

Racism, racism, racism: from beginning to end, the organ and tissue transplant proces is discriminatory and racist. The Donate Life website which is quoted in this piece says…

Of course that is a straightforward lie. See what happens if you are a poor villager in rural Cambodia, and get on an illegal boat to Australia, to get a transplant. The story is the same all over the developed world: the most privileged in health care, have the best access to donor organs and tissue – ‘white’ (ethnic majority) male, university educated, high-income. Transplants are organised on a national basis, and the coordinators shamelessly discriminate on grounds of nationality. The same goes for donated blood, and what’s more there are semi-secret protocols, on the military use of donated blood. If ethical principles were applied, there would be nothing left of the present donor systems.

Is it that the organ and transplant process is discriminatory and racist, or is it that immigration policy is discriminatory and racist?

Both are racist and intertwined, and not just in Australia. To get any medical treatment you have to have formal access to medical care. You need money / insurance, and often legal residence, it varies from country to country. To get insurance, you generally need legal residence anyway. For a transplant, obviously, the checks will be more rigorous. Any border controls obstruct access to medical care, and this is not a trivial issue – access to medical treatment is surprisingly often given as a reason to seek asylum in north-western Europe. So even in the unlikely case that a hospital provided a transplant to anyone who walked in the door, that would be no use if border guards prevented certain nationalities and ethnic groups from reaching the hospital. And that’s exactly what they do, sometimes with the explicit goal of avoiding extra health-care costs in the destination country.

Is the family veto only possible in Australia, or are there other countries with similar laws?

I believe that we should abandon the family veto. If a person wants to be an organ donor, then that should definitely be something that is respected and carried out. Seeing as they are deceased, they obviously have no way to defend themselves, which if they could, they would argue the decision of a family member to not allow them to donate their organs. I’m sure there are a few out there that would not go this way, but I think that the majority of situations would be this way. Ethically, participants must have equal opportunity to present arguments (Johannesen,Richard L. 2009). Do you see the deceased being able to defend themselves in this issue? The answer to that is no. No, they cannot and will not defend themselves, therefore it is wrong and the family veto should most definitely be abandoned.

Comments are closed.