The Psychology of Speciesism: How We Privilege Certain Animals Over Others

Written by Lucius Caviola

Our relationship with animals is complex. There are some animals we treat very kindly; we keep them as pets, give them names, and take them to the doctor when they are sick. Other animals, in contrast, seem not to deserve this privileged status; we use them as objects for human consumption, trade, involuntary experimental subjects, industrial equipment, or as sources of entertainment. Dogs are worth more than pigs, horses more than cows, cats more than rats, and by far the most worthy species of all is our own one. Philosophers have referred to this phenomenon of discriminating individuals on the basis of their species membership as speciesism (Singer, 1975). Some of them have argued that speciesism is a form of prejudice analogous to racism or sexism.

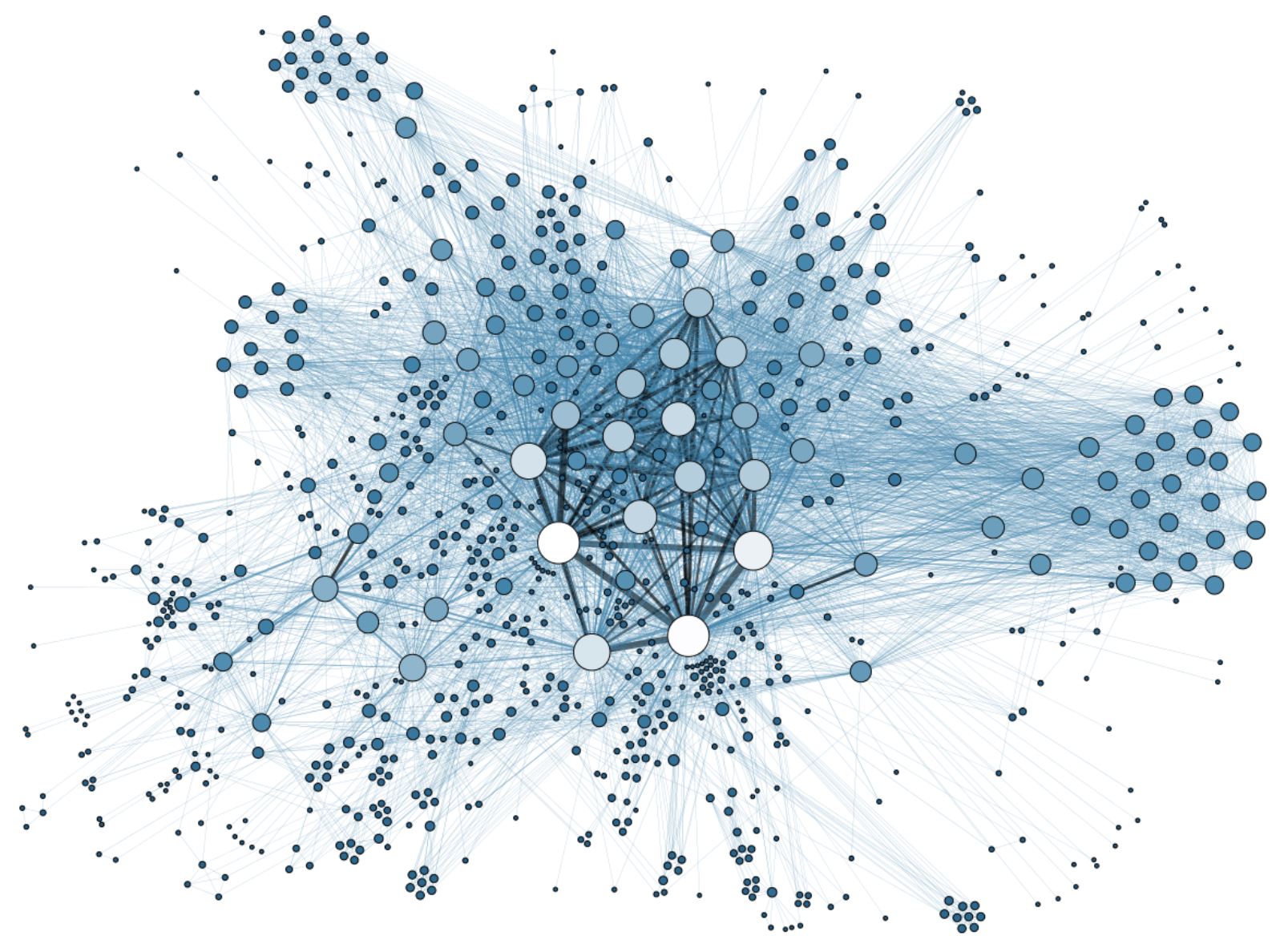

Whether speciesism actually exists and whether it is related to other forms of prejudice isn’t just a philosophical question, however. Fundamentally, these are hypotheses about human psychology that can be explored and tested empirically. Yet surprisingly, speciesism has been almost entirely neglected by psychologists (apart from a few). There have been fewer than 30 publications in the last 70 years on this topic as revealed by a Web of Science search for the keywords speciesism and human-animal relations in all psychology journals. While this search may not be totally exhaustive, it pales in comparison to the almost 3’000 publications on the psychology of racism in the same time frame. The fact that psychology has neglected speciesism is strange, given the relevance of the topic (we all interact with animals or eat meat), the prevalence of the topic in philosophy, and the strong focus psychology puts on other types of apparent prejudice. Researching how we assign moral status to animals should be an obvious matter of investigation for psychology.

Read More »The Psychology of Speciesism: How We Privilege Certain Animals Over Others