How Does Social Media Pose a Threat to Autonomy?

Undergraduate Finalist paper in the 2025 National Uehiro Oxford Essay Prize in Practical Ethics. By Rahul Lakhanpaul, University of Edinburgh.

Undergraduate Finalist paper in the 2025 National Uehiro Oxford Essay Prize in Practical Ethics. By Rahul Lakhanpaul, University of Edinburgh.

Written by Cristina Voinea

2024 is poised to be a challenging year, partly because of the important elections looming on the horizon – from the United States and various European countries to Russia (though, let us admit, surprises there might be few). As more than half of the global population is on social media, much of political communication and campaigning moved online. Enter the realm of online political microtargeting, a game-changer fueled by data and analytics innovations that changed the face of political campaigning.

Microtargeting, a form of online targeted advertisement, relies on the collection, aggregation, and processing of both online and offline personal data to target individuals with the messages they will respond or react to. In political campaigns, microtargeting on social media platforms is used for delivering personalized political ads, attuned to the interests, beliefs, and concerns of potential voters. The objectives of political microtargeting are diverse, as it can be used to inform and mobilize or to confuse, scare, and demobilize. How does political microtargeting change the landscape of political campaigns? I argue that this practice is detrimental to democratic processes because it restricts voters’ right to information. (Privacy infringements are an additional reason but will not be the focus of this post).

Read More »Political Campaigning, Microtargeting, and the Right to Information

This is the first in a series of blogposts by the members of the Expanding Autonomy project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council

Written By: J Adam Carter, COGITO, University of Glasgow

E-mail: adam.carter@glasgow.ac.uk

What are things going to be like in 100 years? Here’s one possible future, described in Michael P. Lynch’s The Internet of Us. He invites us to imagine:

smartphones are miniaturized and hooked directly into a person’s brain. With a single mental command, those who have this technology – let’s call it neuromedia – can access information on any subject ….

That sounds pretty good. Just think how quickly you could gain information you need, and how easy and intellectually streamlined the process would be. But here is the rest of the story:

Now imagine that an environmental disaster strikes our invented society after several generations have enjoyed the fruits of neuromedia. The electronic communication grid that allows neuromedia to function is destroyed. Suddenly no one can access the shared cloud of information by thought alone. . . . [F]or the inhabitants of this society, losing neuromedia is an immensely unsettling experience; it’s like a normally sighted person going blind. They have lost a way of accessing information on which they’ve come to rely.Read More »Cross Post: Brainpower: Use it or Lose it?

Written by Muriel Leuenberger

A modified version of this post is forthcoming in Think edited by Stephen Law.

Spoiler warning: if you want to watch the movie Don’t Worry Darling, I advise you to not read this article beforehand (but definitely read it afterwards).

One of the most common reoccurring philosophical thought experiments in movies must be the simulation theory. The Matrix, The Truman Show, and Inception are only three of countless movies following the trope of “What if reality is a simulation?”. The most recent addition is Don’t Worry Darling by Olivia Wilde. In this movie, the main character Alice discovers that her idyllic 1950s-style housewife life in the company town of Victory, California, is a simulation. Some of the inhabitants of Victory (most men) are aware of this, such as her husband Jack who forced her into the simulation. Others (most women) share Alice’s unawareness. In the course of the movie, Alice’s memories of her real life return, and she manages to escape the simulation. This blog post is part of a series of articles in which Hazem Zohny, Mette Høeg, and I explore ethical issues connected to the simulation theory through the example of Don’t Worry Darling.

One question we may ask is whether living in a simulation, with a simulated and potentially altered body and mind, would entail giving up your true self or if you could come closer to it by freeing yourself from the constraints of reality. What does it mean to be true to yourself in a simulated world? Can you be real in a fake world with a fake body and fake memories? And would there be any value in trying to be authentic in a simulation?

Written by Stephen Milford, PhD

Institute for Biomedical Ethics, Basel University

The rise of AI presents humanity with an interesting prospect: a companion species. Ever since our last hominid cousins went extinct from the island of Flores almost 12,000 years ago, homo Sapiens have been alone in the world.[i] AI, true AI, offers us the unique opportunity to regain what was lost to us. Ultimately, this is what has captured our imagination and drives our research forward. Make no mistake, our intentions with AI are clear: artificial general intelligence (AGI). A being that is like us, a personal being (whatever person may mean).

If any of us are in any doubt about this, consider Turing’s famous test. The aim is not to see how intelligent the AI can be, how many calculations it performs, or how it shifts through data. An AI will pass the test if it is judged by a person to be indistinguishable from another person. Whether this is artificial or real is academic, the result is the same; human persons will experience the reality of another person for the first time in 12 000 years, and we are closer now than ever before.Read More »Guest Post: Dear Robots, We Are Sorry

By Ben Davies

When new technologies emerge, ethical questions inevitably arise about their use. Scientists with relevant expertise will be invited to speak on radio, on television, and in newspapers (sometimes ethicists are asked, too, but this is rarer). In many such cases, a particular phrase gets used when the interview turns to potential ethical issues:

“We need to have a conversation”.

It would make for an interesting qualitative research paper to analyse media interviews with scientists to see how often this phrase comes up (perhaps it seems more prevalent to me than it really is because I’ve become particularly attuned to it). Having not done that research, my suggestion that this is a common response should be taken with a pinch of salt. But it’s undeniably a phrase that gets trotted out. And I want to suggest that there are at least two issues with it. Neither of these issues is necessarily tied together with using this phrase—it’s entirely possible to use it without raising either—but they arise frequently.

In keeping with the stereotype of an Anglophone philosopher, I’m going to pick up on a couple of key terms in a phrase and ask what they mean. First, though, I’ll offer a brief, qualified defence of this phrase. My aim in raising these issues isn’t to attack scientists who use it, but rather to ask that a bit more thought is put into what is, at heart, a reasonable response to ethical complexity.

Read More »We Need To Have A Conversation About “We Need To Have A Conversation”

Written by Muriel Leuenberger

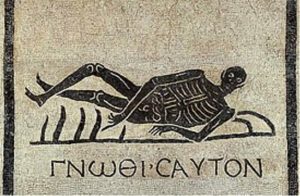

The ancient Greek injunction “Know Thyself” inscribed at the temple of Delphi represents just one among many instances where we are encouraged to pursue self-knowledge. Socrates argued that “examining myself and others is the greatest good” and according to Kant moral self-cognition is ‘‘the First Command of all Duties to Oneself’’. Moreover, the pursuit of self-knowledge and how it helps us to become wiser, better, and happier is such a common theme in popular culture that you can find numerous lists online of the 10, 15, or 39 best movies and books on self-knowledge.

Read More »Track Thyself? Personal Information Technology and the Ethics of Self-knowledge

Written by Stephen Rainey

Artificial intelligence (AI) is anticipated by many as having the potential to revolutionise traditional fields of knowledge and expertise. In some quarters, this has led to fears about the future of work, with machines muscling in on otherwise human work. Elon Musk is rattling cages again in this context with his imaginary ‘Teslabot’. Reports on the future of work have included these replacement fears for administrative jobs, service and care roles, manufacturing, medical imaging, and the law.

In the context of legal decision-making, a job well done includes reference to prior cases as well as statute. This is, in part, to ensure continuity and consistency in legal decision-making. The more that relevant cases can be drawn upon in any instance of legal decision-making, the better the possibility of good decision-making. But given the volume of legal documentation and the passage of time, there may be too much for legal practitioners to fully comprehend.

Read More »Judgebot.exe Has Encountered a Problem and Can No Longer Serve

Written by Stephen Rainey

An excitingly futuristic world of seamless interaction with computers! A cybernetic environment that delivers what I want, when I want it! Or: A world of built on vampiric databases, fed on myopic accounts of movements and preferences, loosely related to persons. Each is a possibility given ubiquitous ambient intelligence.Read More »Ambient Intelligence

This essay received an honourable mention in the undergraduate category.

Written by University of Oxford student, Angelo Ryu.

Introduction

The scope of modern administration is vast. We expect the state to perform an ever-increasing number of tasks, including the provision of services and the regulation of economic activity. This requires the state to make a large number of decisions in a wide array of areas. Inevitably, the scale and complexity of such decisions stretch the capacity of good governance.

In response, policymakers have begun to implement systems capable of automated decision making. For example, certain jurisdictions within the United States use an automated system to advise on criminal sentences. Australia uses an automated system for parts of its welfare program.

Such systems, it is said, will help address the costs of modern administration. It is plausibly argued that automation will lead to quicker, efficient, and more consistent decisions – that it will ward off a return to the days of Dickens’ Bleak House.Read More »Oxford Uehiro Prize in Practical Ethics: What, if Anything, is Wrong About Algorithmic Administration?