Simulate Your True Self

Written by Muriel Leuenberger

A modified version of this post is forthcoming in Think edited by Stephen Law.

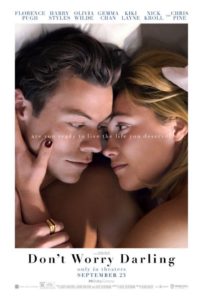

Spoiler warning: if you want to watch the movie Don’t Worry Darling, I advise you to not read this article beforehand (but definitely read it afterwards).

One of the most common reoccurring philosophical thought experiments in movies must be the simulation theory. The Matrix, The Truman Show, and Inception are only three of countless movies following the trope of “What if reality is a simulation?”. The most recent addition is Don’t Worry Darling by Olivia Wilde. In this movie, the main character Alice discovers that her idyllic 1950s-style housewife life in the company town of Victory, California, is a simulation. Some of the inhabitants of Victory (most men) are aware of this, such as her husband Jack who forced her into the simulation. Others (most women) share Alice’s unawareness. In the course of the movie, Alice’s memories of her real life return, and she manages to escape the simulation. This blog post is part of a series of articles in which Hazem Zohny, Mette Høeg, and I explore ethical issues connected to the simulation theory through the example of Don’t Worry Darling.

One question we may ask is whether living in a simulation, with a simulated and potentially altered body and mind, would entail giving up your true self or if you could come closer to it by freeing yourself from the constraints of reality. What does it mean to be true to yourself in a simulated world? Can you be real in a fake world with a fake body and fake memories? And would there be any value in trying to be authentic in a simulation?